The stand-out exhibitions of 2018, and what to look out for in 2019

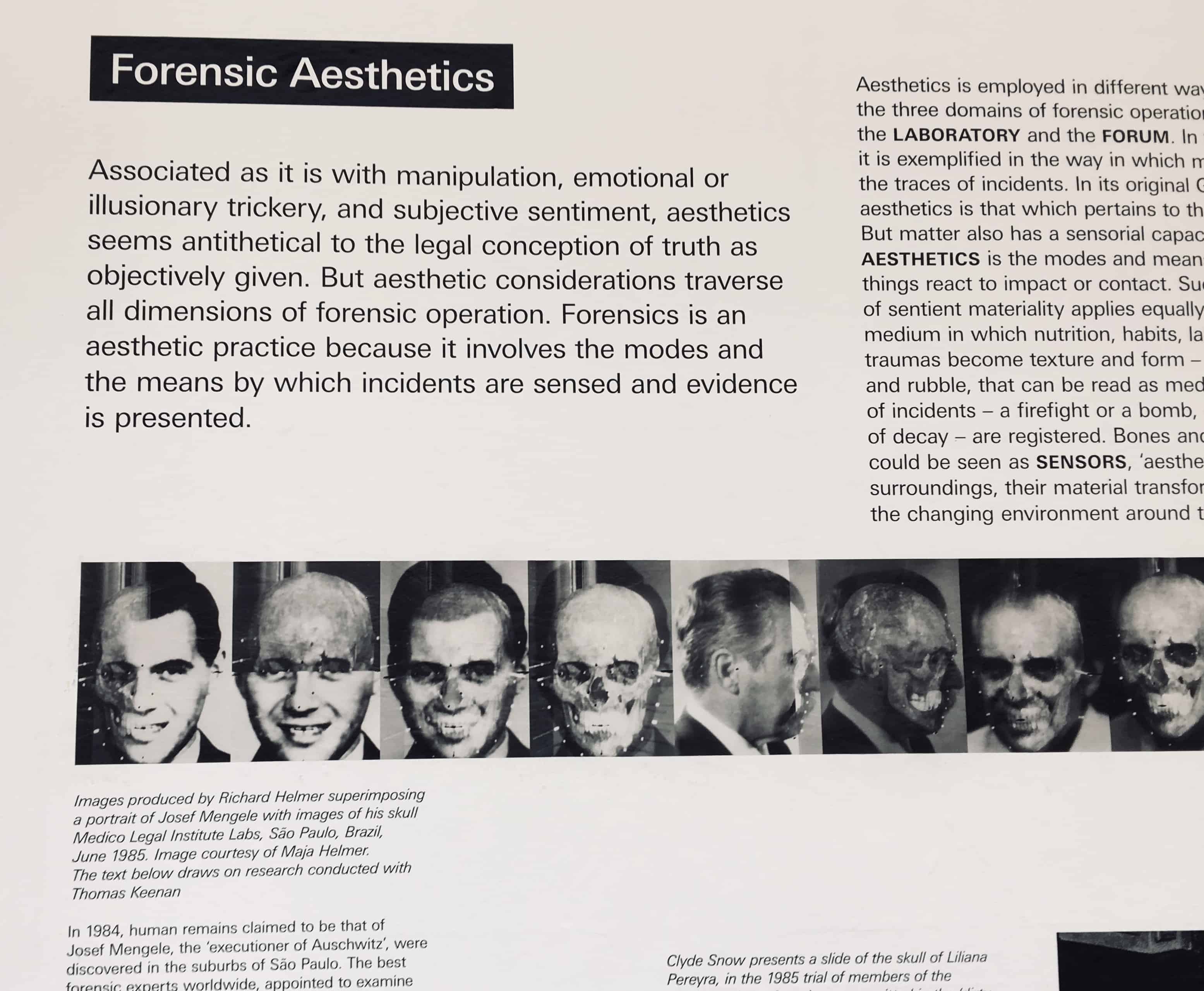

Counter Investigations: Forensic Architecture, ICA

The ICA’s survey of the research and human rights advocacy agency Forensic Architecture, showed exactly why they deserved to be on last year’s Turner Prize shortlist ‘But is it art?’, you might ask, to which one might shrug and say, ‘Dunno, ask Arthur Danto, but it does everything that great art can.’ And, of course it does far more beyond the exhibition walls.

Based at Goldsmith’s College, and comprising an interdisciplinary team of architects, filmmakers, artists, scientists, and lawyers to investigate instances of state violence, the agency work with other human rights organisations, including Amnesty International, to present their findings in courts, tribunals, and the UN. I first came across their work through the Beirut and Berlin-based artist Lawrence Abu Hamdan, but it wasn’t until the ICA’s exhibition, which I caught on the very last day (phew), that I fully appreciated how compellingly they present their research, as visual, aural and text-based data and witness testimony. That they’re getting this level of exposure is a great thing. We need people to do this work.

Read my Turner Prize 2018 here, plus my Q&A with artist Lawrence Abu Hamdan, who explains his work with Forensic Architecture.

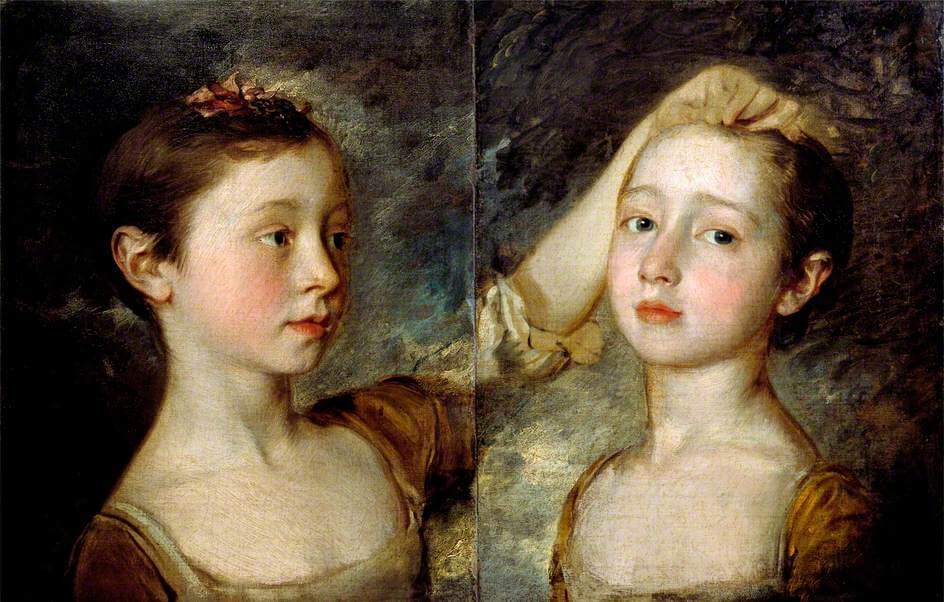

Gainsborough’s Family Album, National Portrait Gallery

Though it made his name and reputation, Gainsborough often resented having to paint commissioned portraits of local gentry. Like Rubens, his first love was landscape painting. But though we may have largely forgotten his cosily idyllic depictions of West Country woodland, his portraits have stood the test of time.

Fleshing out the man through his art, Gainsborough’s Family Album is a surprisingly moving survey of portraits – loosely painted, often unfinished – of those in the artist’s intimate circle. The mastery in those feathery brushstrokes, the exquisitely painted layers of diaphanous fabric, the arresting tenderness of portraits of his daughters as they emerge from childhood into adulthood, reveal why Gainsborough really is one of the greats of European painting and, of course, the Rococo. As an intimate engagement with the artist, this exhibition can’t be bettered. Ends 3 February

Picasso 1932 – Love, Fame, Tragedy, Tate Modern

What, another Picasso exhibition, you say? Surprisingly, this was the first solo Picasso survey at Tate Modern (previously there had been a brilliant Matisse-Picasso paint-off, exploring life-long rivalry and friendship). And was it good? Oh yes. Focusing on just one year of Picasso’s prolific output – his ‘year of wonders’ according to his friend and biographer John Richardson – Tate’s exhibition had some pretty staggering loans, including the wittily sensual The Dream and the beguiling, utterly seductive Woman Reading (pictured).

1932 was the year the artist turned 50, the year of his first large-scale retrospective, at the Galeries Georges Petit, Paris, and the year he painted, sculpted and drew hundreds of portraits of his young lover Marie-Thérèse Walter, whilst still living with his first wife, Olga. Mrs Picasso got just one portrait in the exhibition, in a room recreating in part that first retrospective. Meanwhile, the exhibition chronicled, month by month, the work he was producing at a feverish rate leading up to it. It also documented his shift in direction in the second half of the year, when he’d once again retreated to his Boisgeloup studio, in Normandy. But it’s his portraits of Walter that are among his finest works, taking us through a myriad of styles and moods. So, so good.

Watch my short film of Picasso 1932 here, and read my review of exhibition right here.

Ribera: The Art of Violence, Dulwich Picture Gallery

Spanish Baroque artist Jusepe de Ribera lived and worked in Naples for most of his life. It was then under Spanish rule, and so he witnessed first hand the grotesque iniquities of the Inquisition. He painted saints and sinners in extremis, and this brilliantly contextualised and intelligent exhibition questions the long-held assumption that Ribera was rather too fond of depicting cruelty for its own sake. On the contrary, say the curators, his depictions of physical suffering are the result of an acute religious and social engagement with his times, when petty criminals and blasphemers, and those who had simply displeased the church authorities, underwent slow and tortuous punishment or death in public squares (the strappado was a favoured punishment, and Ribera sketched its unfortunate victims). And who, apart from Rembrandt, could paint ageing flesh as well as Ribera? He is one of the underrated greats of the Baroque. Ends 27 January

Amy Sillman: Landline, Camden Arts Centre

Camden Arts Centre has been at the forefront of showcasing women artists when other institutional venues, and until recently this includes Tate, were hardly seeming to be making an effort. This was largely down to the good work of its former director Jenni Lomax. The gallery was the first in the UK to have an exhibition of Hilma af Klint, a decade before the Serpentine’s retrospective of the occult Swedish artist. And it’s carried on this tradition by focusing on living women artists who are little-known in the UK. In that tradition, this is superb introduction to the paintings and silkscreens of American artist Amy Sillman. Veering between abstraction and figuration, we find hints of Philip Guston, Sigmar Polke, Albert Oehlen. It’s a heady brew – catch it while you can. Ends 6 January

Ed Ruscha: Course of Empire, National Gallery

This small, free exhibition was a complement to the National Gallery’s Thomas Cole exhibition, whose famous cycle The Course of Empire (1833-36) features the rise and fall of a civilisation, from its state of savage wilderness to its ideal as an American pastoral, to its ruination by vulgar excess, hubris and greed, and, finally, to its return to a state of nature.

As a direct echo and witty homage, Ruscha’s Course of Empire focused on the industrial buildings of Los Angeles, painted in flat acrylic in Ruscha’s characteristically geometric, elegantly graphic, pared-down style, where words and logos take on a special prominence, their meanings becoming pointedly ambiguous.

These before and after paintings featured imposing worm-eye views of warehouse-type structures beneath lowering skies, giving an account of their commercial fortunes over a span of time. Ruscha has such an extraordinarily impeccable sense of composition, and if you’re a fan of his great Standard Station prints you wouldn’t want to have missed this.

Klimt / Schiele: Drawings from the Albertina Museum, Vienna, Royal Academy

Gustave Klimt was the great ennobled artist of the Vienna Secession, while Egon Schiele was the brilliant upstart. Schiele emulated Klimt, yet, in his short, troubled life, managed to surpass him. Klimt painted decorative, elegant canvases that exude a icily cool, cut-glass eroticism. His drawings were largely sketches and studies for his paintings and mural work – there is only one highly finished work in this exhibition, which exists as a drawing in its own right. Schiele’s drawings, by contrast, were works in themselves. So you can immediately see why putting their drawing and sketches together puts Klimt at a disadvantage. But it’s more than that – there’s a vitality to Schiele’s exquisite line that makes him by far the more exciting artist. Just compare their two poster designs for the Vienna Secession, of which Klimt was the founding president, and compare Klimt’s coolly elegant, archaic forms with Schiele’s cruder, more ‘primitivist’ and expressive design. Having said all this, I still think this is a terrific, unmissable exhibition exploring the similarities and the differences of two artists at the very centre of Austria’s avant-garde. Ends 3 February

Kerry James Marshall: History of Painting, David Zwirner London

So, I’m going to give another heads up to Camden Arts Centre. Not only was the gallery at the forefront of exhibiting neglected women artists way before other UK institutes, but it was here, in 2005, that I encountered the paintings of Kerry James Marshall for the first time in the flesh. And wow. The African-American artist has been centring the black subject in his paintings since the 1980s, and his work keeps getting better.

This commercial gallery show featured three recent but distinct bodies of work: abstract paintings consisting of flat lozenges in neon-bright colours; pop ‘trompe-l’œil‘ paintings of supermarket-type flyers carrying the auction prices of big-name artists, some with ‘stickers’ revealing whether they’d reached their estimated value; and figurative paintings that nod to a history of Western painting, including two half length portraits in imitation of the Renaissance marriage portrait.

The star of the exhibition, however, was Untitled (Underpainting) (pictured), a contemporary masterpiece. Painted to resemble a diptych, its two ‘panels’ formally mirror each other though show different scenes in a museum gallery populated by an exclusively black audience. The two sides are separated by a two white vertical strips, on which Marshall has attached two actual museum wall labels. I hardly need say that there’s a lot going with regard to the politics of seeing and representation and that it would probably need a whole thesis. Plus, Marshall is just an extraordinarily good painter.

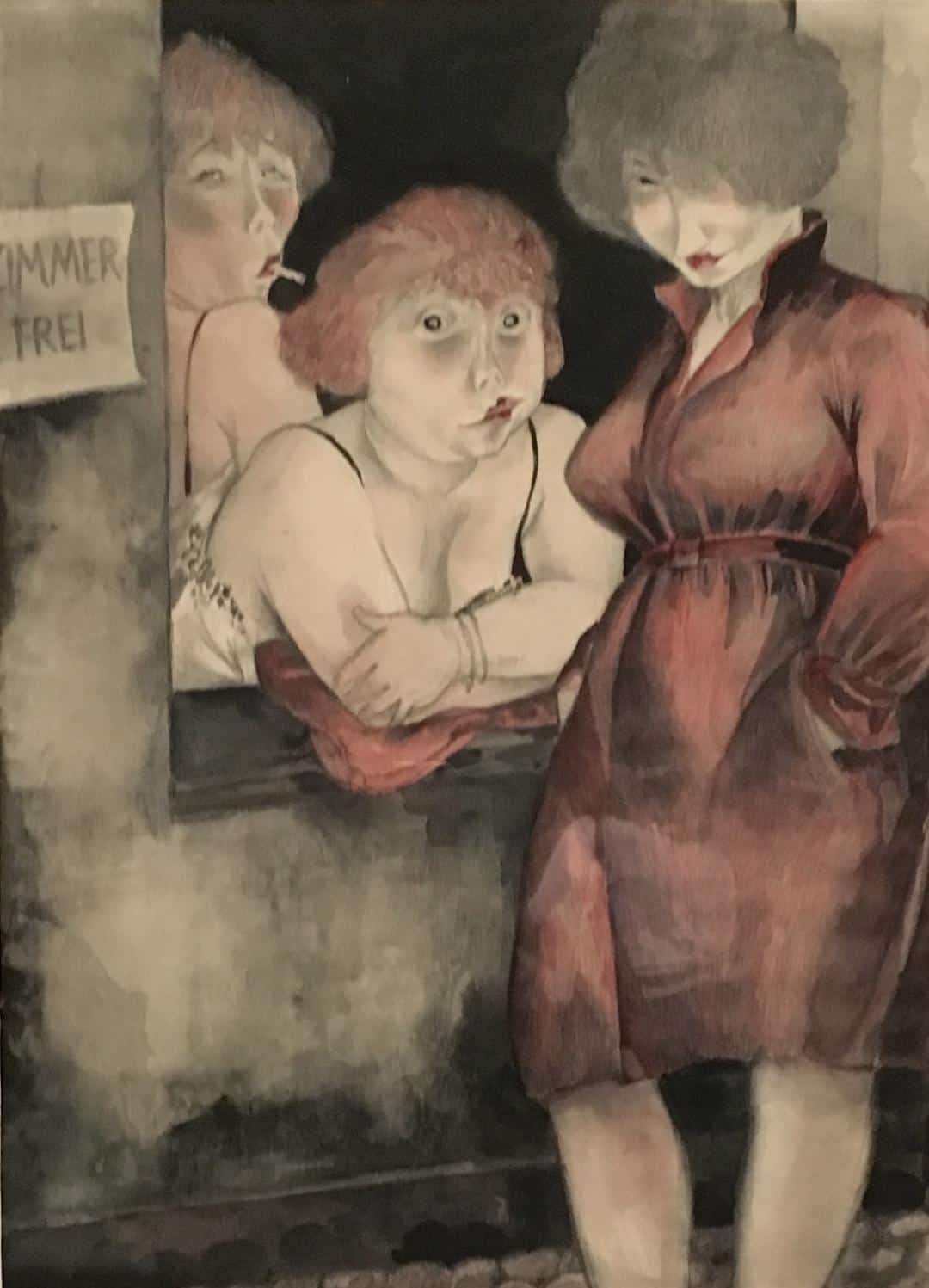

Magic Realism: Art in Weimar Germany, 1919-1933, Tate Modern

German art of the interwar years – it seems museum curators haven’t been able to get enough of it lately. Otto Dix, August Sander, Käthe Kollwitz, Max Beckmann, are just a few of the artists featured in major exhibitions. A room devoted to the graphic art of Dix, Kollwitz, George Grosz and others in Aftermath: Art in the Wake of World War One at Tate Britain, was by far the strongest room in the exhibition – incredibly visceral, savagely satirical. But it’s Tate Modern’s free display, Magic Realism, (it doesn’t end until well into the summer so plenty of time to still catch it), that really captured my imagination, introducing me to a host of German artists who are rarely shown in anthologies, including Jeanne Mammen, who portrayed tough, independent, and earthily sensual women, working in bars, plying their trade in brothel houses, and just trying to survive at the fag end of the Weimar Republic. Ends 14 July

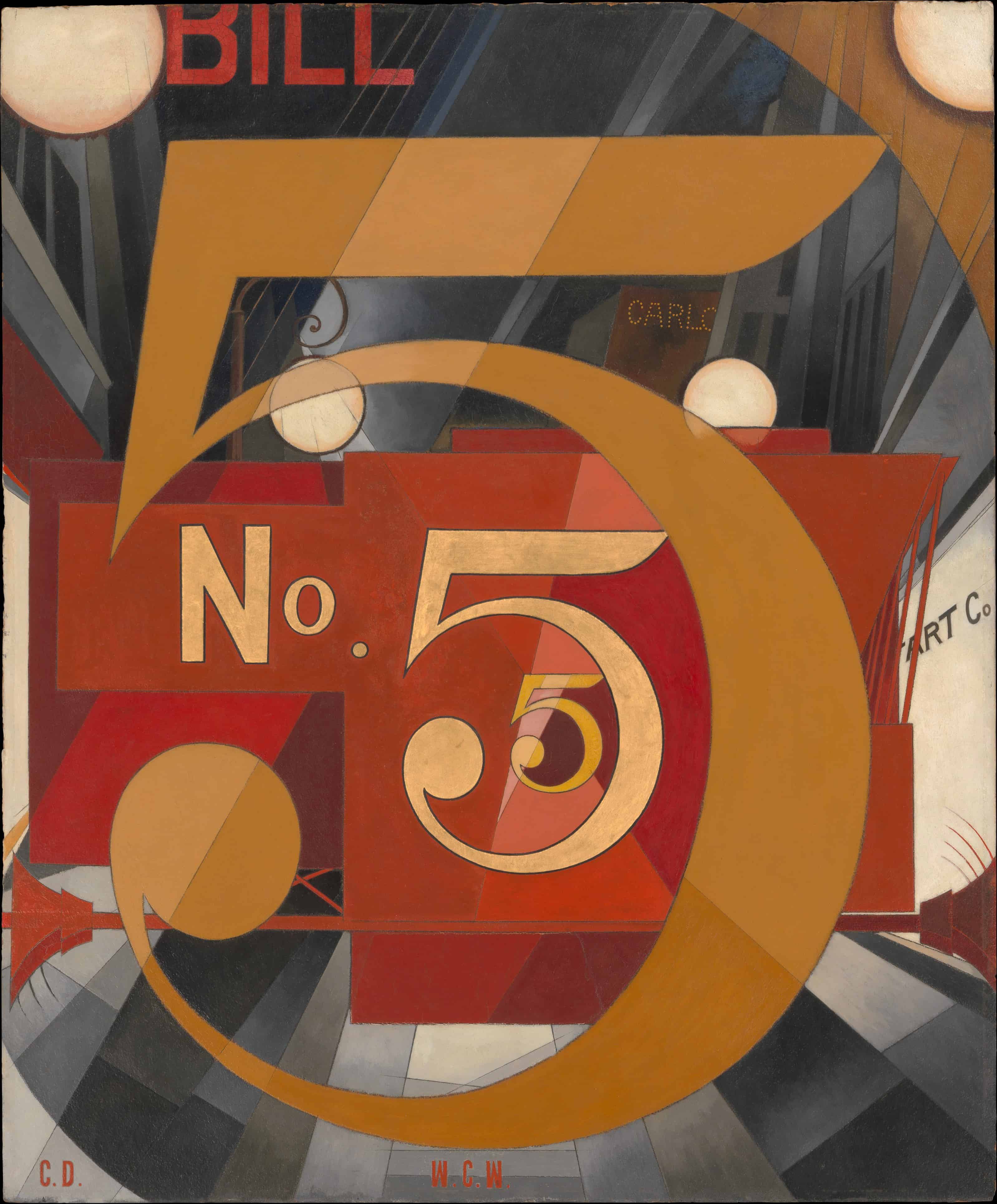

America’s Cool Modernism: O’Keeffe to Hopper, Ashmolean Museum

Finally, I managed to get out of London…but only to Oxford. I was impressed by the Ashmolean’s America’s Cool Modernism both because it managed to get some truly impressive loans, not least of all Charles Demuth’s celebrated I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold, 1928, which usually hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, but also because there are so few early 20th century American paintings in our own public collections. This meant that this riveting anthology was a chance to get acquainted with artists who are rarely seen or heard of outside the US, where American Modernism usually starts with Pollock.

There were quite a few Arthur Dove, a painter influential to Georgia O’Keeffe, there was George Ault, including his eerily atmospheric 1932 painting Hoboken Factory. There were lots of Charles Sheelers, but not just his coolly brilliant Precisionist paintings of factories and silos. Here we also had his 1921 film, Manhatta, made with photographer Paul Strand, which explores a day in the life of Manhattan set against the words of Walt Whitman. And, of course, there was Edward Hopper and Stuart Davis, with paintings by the latter that predated those jazzy, rhythmic paintings he’s better known for.

Read my review of America’s Cool Modernism here.

Art highlights of 2019

Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory, Tate Modern

23 January to 6 May

What a way to start the year. Along with Matisse, Bonnard is one of the great colourists of the 20th century and his quiet domestic scenes, not withstanding all those subtler lavender-silver paintings of his ageless wife soaking in the bath, shimmer and glow with their fiery hues. He rarely painted in front of his subject, preferring to paint from memory, as if through the heat haze of a dream. This exhibition takes us from 1912, when Bonnard really begins experimenting with colour, and ends in 1947, the year he died.

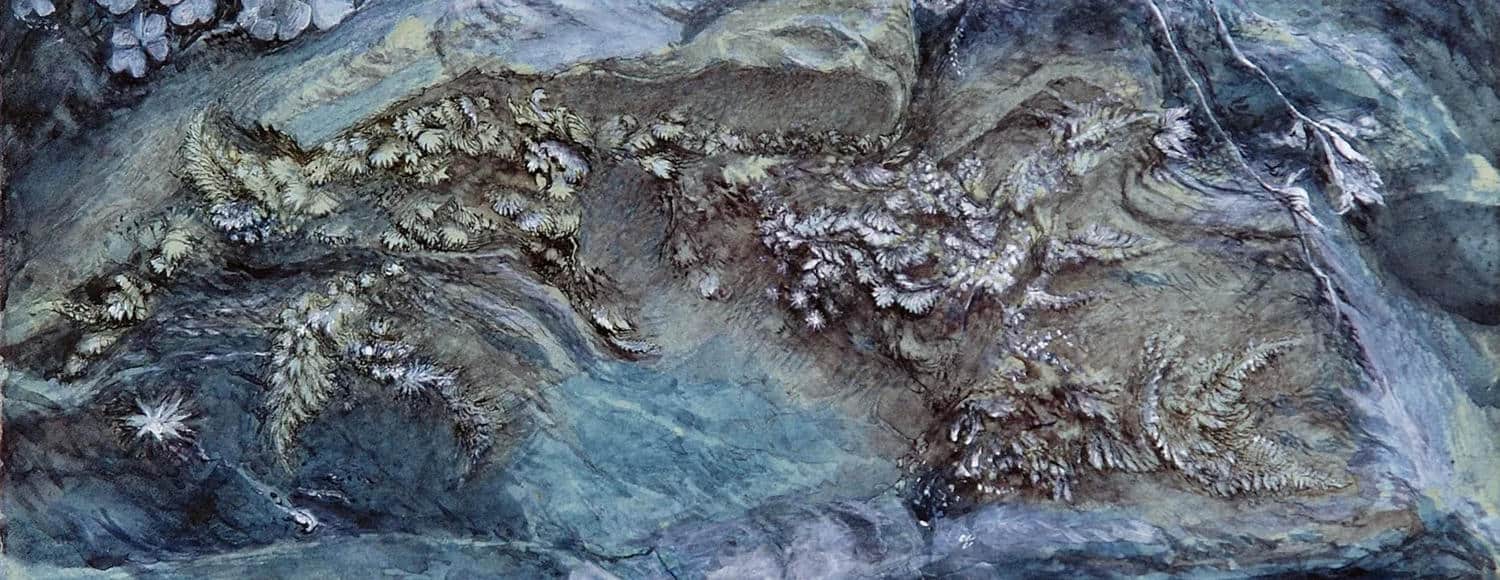

John Ruskin: The Power of Seeing, Two Temple Place

26 January to 22 April

John Ruskin was an artist, a social thinker, a philanthropist, an art patron, a voluminous art writer and critic, and he is perhaps best known as JMW Turner‘s most ardent champion. There are so many bows to this 19th-century polymath – a man more recently maligned as a pompous popinjay in Mike Leigh’s film Turner – that an exhibition on the bicentenary of his birth should help at least give a more rounded picture of the man, his ideas, his philanthropic causes, and his circle.

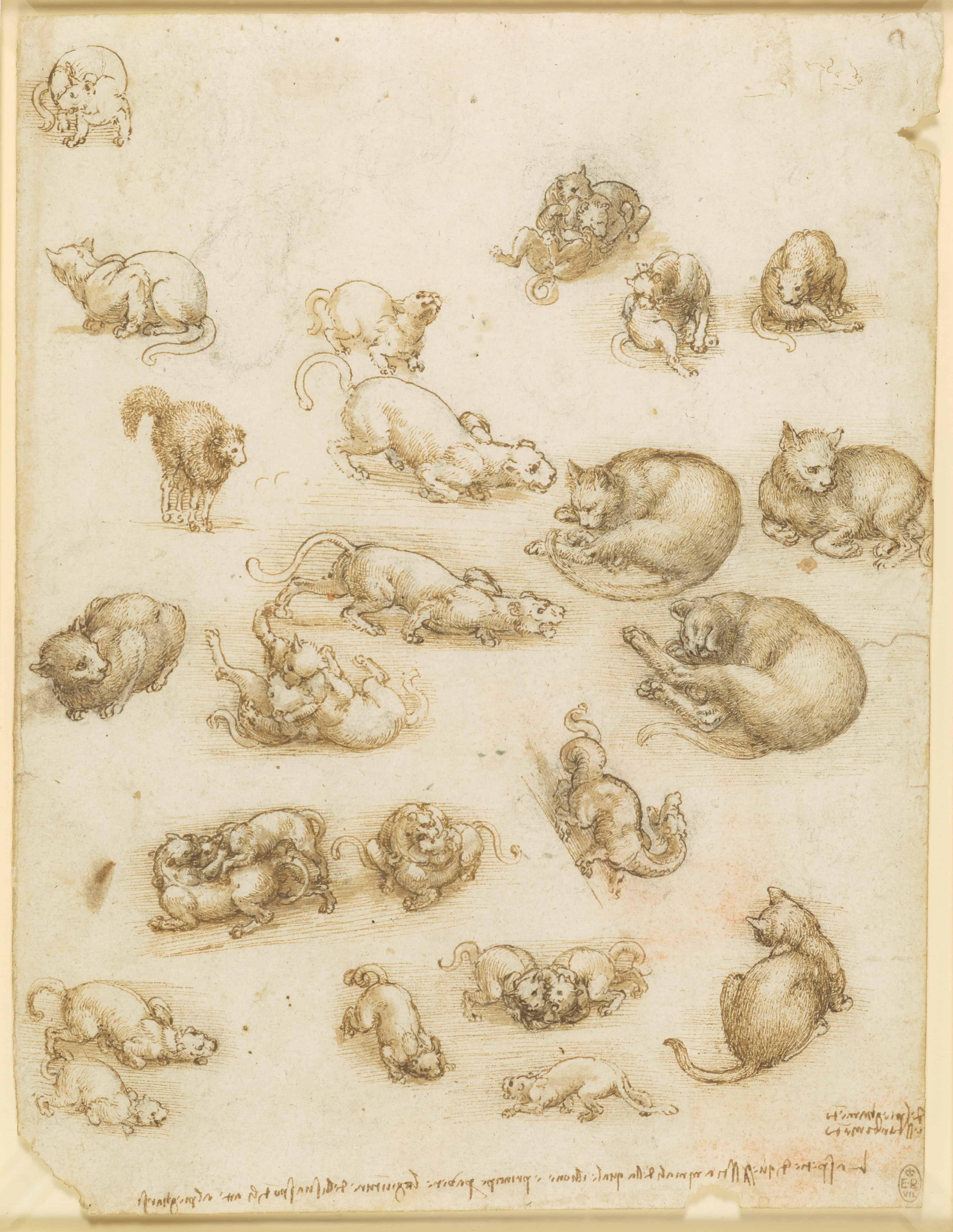

Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing, various UK venues

From February, to mark the 500th anniversary of the death of Leonardo da Vinci, 144 of the Renaissance artist’s drawings in the Royal Collection will go on display in 12 simultaneous exhibitions across the UK. In May, the drawings will then be brought together to form part of an exhibition of over 200 at The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, the largest exhibition of Leonardo’s work in over 65 years. Later in the year, a selection of 80 will travel to The Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse, the largest group of Leonardo’s works ever shown in Scotland. Wooo.

Lee Krasner: Living Colour, Barbican Art Gallery

30 May – 1 September

Like many of her New York School peers, Lee Krasner studied under the hugely influential artist, teacher and art theorist Hans Hofmann, who once offered her the, er, compliment that her work was so good that ‘you would not know it was made by a woman artist.’ Unfortunately for her, it mattered that she was, and her work was only really championed in the 70s, when leading feminist critics promoted it. Luckily, she was still around to enjoy her belated success, though she died in 1984 just before a retrospective of her paintings and collages was due to open at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Of course, she was also the wife of Jackson Pollock, so as well as struggling under his shadow, Krasner allowed her own career to be put on hold to devote herself to his. But now UK audiences will get a chance to see just how well her work holds up against all of her abstract expessionist peers – which it peerlessly does.

Helene Schjerfbeck, Royal Academy

20 July to 27 October

Who’s Helene Schjerfbeck, you might well ask. Well, she’s a Finnish artist who was born in 1862 and died in 1946, and whose paintings are almost exclusively in Finnish collections. She was influenced by the French avant-garde, yet her paintings have a chillier Northern European sensibility. From the naturalism of her earlier style, she began moving increasingly towards abtracted figuration, and her self-portraits, many of which show her features decaying and skull-like in later life, are among her signature images.

It was at Helsinki’s National Museum that I was lucky enough to see a large retrospective of her paintings some years ago. It was the first time I’d ever encountered her name or her work, so, naturally, I’m very excited by this first UK retrospective.

Käthe Kollwitz, British Museum

12 September to 12 January 2020

This exhibition has travelled the country, beginning at Birmingham’s Ikon Gallery in 2017 and ending last year at the Ferens Art Gallery, Hull. The drawings and prints are now returning to the British Museum, which holds the collection, in addition to two works from private collections. I’ve said it many times, but Kollwitz really is among the finest draughtman and printmakers of the 20th century. Witnessing the desperate poverty and deprivation in Berlin, where she lived with her GP husband (she would see the poverty and hunger first hand with his patients) she was an artist whose passionate and radical left-wing politics was harnessed in her work. If you haven’t had a chance to see these extraordinary prints and drawings yet, don’t miss this final stop.

Rembrandt’s Light, Dulwich Picture Gallery

4 October to 2 February, 2020

Another major artist’s death anniversary: as well as Leonardo’s half a millennium, this time we’re commemorating the 350th anniversary of Rembrandt’s death. The biggest event will be the Rijkmuseum’s All the Rembrandts, in which the the museum will, for the first time, present all of its 22 paintings, 60 drawings and more than 300 best examples of Rembrandt’s prints in its collection. The centrepiece will be The Night Watch, just before it undergoes extensive restoration (which will be in public view and livestreamed).

In the UK, we can also look forward to Rembrandt’s Light at the Dulwich Picture gallery, which looks at the way the artist handled light in his paintings. This owes a huge debt to Caravaggio, but Rembrandt’s approach was subtler and more diffuse. A highlight of the exhibitions will be Philemon and Baucis (pictured), on loan from Washington DC’s National Gallery of Art, the first time the painting has travelled to the UK.

Gauguin Portraits, National Gallery

7 October to 26 January

I love Gauguin’s self-portraits more than I’ve ever loved his Tahiti paintings, chiefly because Gauguin loved portraying himself as suffering saint and devilish sinner, even down to a halo or a pair of horns. Here he is (pictured) as Christ with a shock of red hair, in Christ in the Garden of Olives. As well as a group of self-portraits, this exhibition will feature portraits made across his career and in different media, including carvings, and will follow his evolution from his early Impressionism to the Symbolism of his Nabi years and the philosophical and spiritual musings of his Polynesian paintings.