Turner was a brilliantly radical artist. But was he of his time, or outside it?

There is early Turner; there is late Turner. Early Turner is very much of his time: a history and landscape painter in the first half of the 19th century, looking back to the classicism of Claude and the Dutch Golden Age tradition of sombre marine painting; late Turner is outside time, or at least outside his own time. In his final decade, Turner paints his way to the future, gravitating towards formlessness and abstraction. And in these luminous late canvases, where colour-suffused light dissolves form, we find a path to Monet, Rothko, all those American colour field painters, even Twombly.

But let’s stop right there. According to the curators at Tate Britain, the above is a half-baked, somewhat misleading, and wholly ahistorical narrative. There are many faces of Turner, and Modernist precursor is just one of them, but since it’s that one which seems to speak most directly to us today it is naturally the most compelling, the most familiar. And why wouldn’t it make most sense to us? What, after all, is art if it’s merely a historical artefact? And doesn’t art history always mark a ceaseless trajectory, at least from our standpoint, even though the often spurious notion of progress is inevitably invoked?

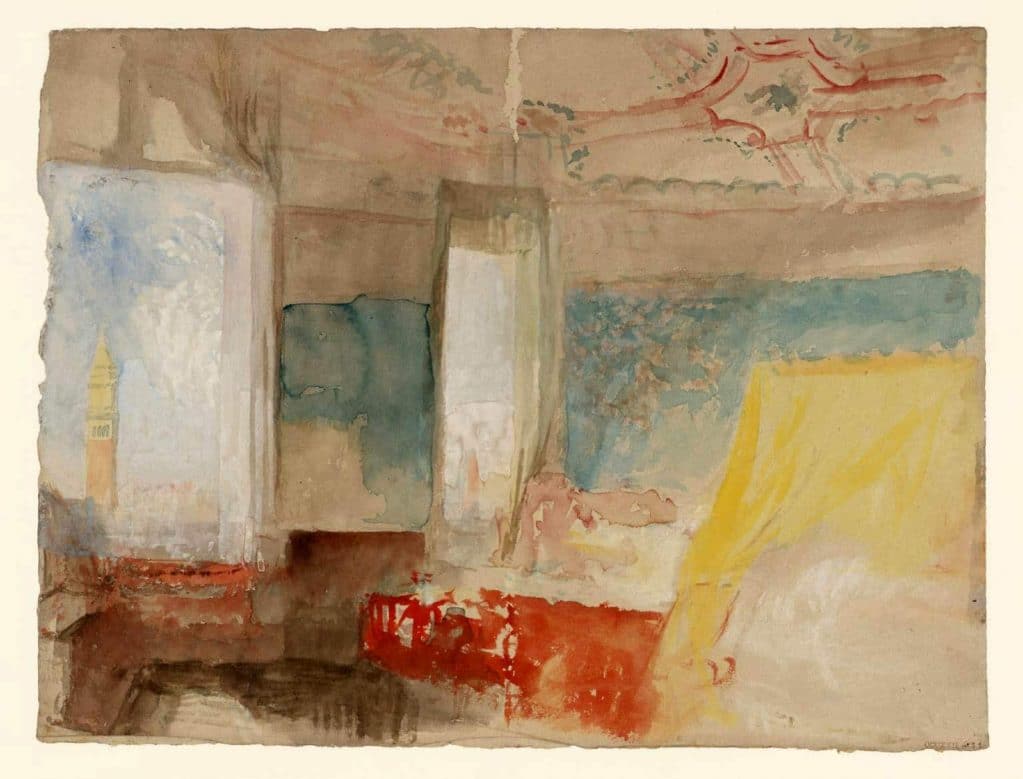

In 1966 New York’s Museum of Modern Art, with the British artist, Tate trustee and curator Lawrence Gowing, staged an exhibition of Turner’s late paintings, including unfinished canvases discovered late in the 20th century, as well as a selection of his most freely painted watercolours (these, with their shimmering veils of colour floating freeform on otherwise unblemished paper, possessing an extra freshness and immediacy (pictured: Turner’s Bedroom in the Palazzo Giustinian, Venice, c.1840). Divested of their 19th-century frames, many of these paintings were reframed in the manner of modern paintings. It wasn’t difficult to see the connections across the span of a century, towards the abstract expressionist works that made up much of MoMA’s permanent collection.

But this latest exhibition wants to do the reverse, to reclaim Turner for history. It wants us to understand Turner as an artist very much engaged with his own time, and to appreciate a continuity in the preoccupations expressed in Turner’s early work with those of his late work – not only with classical mythology and history painting, but with the age of industrialisation. What’s more, the curators don’t shy away from calling him a “Victorian artist,” a term which, though of course factually accurate for much of his later life and career, is unavoidably, provocatively, loaded. Who doesn’t flinch a little from the use of such a label, for so long a term of disparagement? Just as Gowing’s exhibition proved controversial for taking Turner out of his century, so this seems to be flirting with controversy for trying to take him back to it.

We’ve never been short of Turner exhibitions, so does Late Turner: Painting Set Free explain his genius to us more eloquently than any of the other myriad exhibitions in recent memory? One exhibition that explained it better than any I’d previously encountered was Turner and the Sea at the Greenwich Maritime Museum earlier this year, and it redid just what the MoMA exhibition had done, but on a smaller scale. And what an unassuming title for an exhibition whose most surprising feature was its sheer wow factor. Here Turner was not only competing with his contemporaries and immediate artistic forebears, but with himself.

One monumental painting at that GMM exhibition, The Battle of Trafalgar, completed in 1824 – he was almost 50, so hardly a callow youth – stops you in your tracks for all the wrong reasons: the dying figures in the foreground are unconvincing and its patriotism both awkward and bombastic. Its enormous size may have simply defeated him. Yet it’s the contrast between that and what followed, as you proceeded and found paintings of breathtaking sublimity, albeit among the many that were unfinished (yes, these could have been painted by a brilliant abstract expressionist), that proved the masterstroke. And unfinished or not, it was the sheer dazzling facility with paint that so impressed, and the absolute economy of means with which so much could be preternaturally evoked. Here was a true modern, and look how far behind he left his contemporaries.

Tate Britain’s current exhibition has a much more arresting title, though the curatorial conceit seems strangely intent on pulling against it. It promises “freedom”, yet tells us that here is a Victorian, setting himself towards the concerns of his age. But we know of course that his greatest concern was the exploration of light and colour, which the exhibition’s wall panels dwell on hardly at all. But if you can’t see it with your own eyes, you can surely read of it in at least one of his paintings’ rather epic titles: Light and Colour (Goethe’s Theory) – the Morning after the Deluge – Moses Writing the Book of Genesis, 1843, is a swirling vortex of fiery red enfolding a circle of golden light. The painting depicts a further subject – as indicated by its descriptive title – to which we must strain our eyes.

The exhibition focuses on the last 15 years of Turner’s productive life, 1835 to 1850 (he died, having suffered from a series of debilitating ailments including a slow loss of vision, in December 1851, though he remained remarkably active and able to travel abroad and work assiduously for most of the period covered). But for one example, a painting by a younger Royal Academician whom Turner was tutoring (the older artist suggested bringing out in greater relief a lamb in the foreground by adding black to the younger artist’s epic but rather solidly conventional painting), Turner is shown on his own.

It’s a big exhibition, featuring a great many remarkable works, though it seems to reach a natural conclusion two rooms before it ends, with the last room dedicated to a return to studied, highly finished mythological scenes, the last paintings he ever exhibited. As they are intended to, these do pull you up short. These are the paintings he wanted to be seen in public, not those barely descriptive, dematerialising and floating veils of colour, of which there are many perfect examples and to which we ourselves cleave.

We find numerous contrasting yet paired paintings, such as the magnificently brooding and subtle Peace: Burial at Sea (pictured) shown with the almost luridly colour-heightened War: the Exile and Rock Limpet, with its throbbing blood-red passages. Both were painted in 1842, with the first depicting the burial at sea of Scottish artist Sir David Wilkie after he died of typhoid on board ship, while the second refers to the return to Paris of the remains of Napoleon, after he had died in exile in St Helena. Of course, contemporary subjects (or at least ones commemorating events within living memory – Napoleon having died in 1821) featured often in Turner’s late work, two further examples being his series of spectacular canvases depicting the 1834 burning down of the Houses of Parliament and the fire at the Tower of London. Like all of nature’s dramatic effects, pyrotechnics fascinated him.

All artists who are as great and as prolific as Turner will have many faces. Inevitably, curatorial conceits will pull them this way, then another. Ultimately, however, there is always something in these artists that is both compellingly unique and protean. Open your eyes to that and you will love these paintings even more.