The profound influence of the Baroque artist who was dismissed as vulgar

If anything lets you know that greatness is not always assured, at least as conferred by the world and not by one’s own singular estimation, it’s the reputation of artists. They go up, they go down. They might be consigned to the dusty storerooms of history for centuries.

If you’re looking for ready evidence of fortune’s fickleness you might, for example, head to the Dulwich Picture Gallery for their current exhibition. Adriaen van de Velde is not a name to arouse the superlatives reserved for the likes of Rembrandt or Vermeer (two artists, incidentally, whose reputations have sorely suffered or languished, but then soared), but it once was. His masterpiece, The Hut, depicting an idyllic pastoral scene, fetched an unusually high price – staggering at the time, the exhibition curators tell us: in 1822, the Rijksmuseum purchased the small painting for 8290 guilders.

But perhaps this master of the Dutch Golden Age was eventually considered too buoyantly French or romantically Italianate, at least for those connoisseurs looking for a purer (a dourly protestant?) vision of 17th-century Dutch landscape painting (today the more celebrated Jacob van Ruisdael fits the bill here). But who really knows? There are myriad reasons for changes of taste and fashion and artists are subject to them.

Which leads to Caravaggio. We all extol the Italian baroque painter for his ‘cinematic’ vision – critics nearly always praise this filmic quality – but there was no cinema during the three centuries in which he was overlooked and even traduced. And for English critics such as John Ruskin and Roger Fry this is certainly not what they saw. They were instead aghast at his vulgarity, his excessive theatricality, his deformation of the cool classical ideal which kept emotions in check but which encouraged a more detached, thus higher, more refined, aesthetic appreciation.

One could, as we find, have too much reality when faced with the robust realism, the sheer life force, of a Caravaggio. And the artist’s willingness to grab ordinary people off the streets to use as his models, so that his devotional saints were depicted as if they really were real-life characters inhabiting the dusty streets of contemporary Rome or Naples or Sicily, with their craggy, sun-burned features and sooty feet, not to mention his boy models, their complexions swarthy, their fingernails grubby, and their appetites evidently lusty – all that fidgety, unsuppressed energy, all that slippery, squirming young flesh – was all too much. In fact, you could say that Ruskin was spot-on when he charged Caravaggio with filling his paintings with “the horror and ugliness and filthiness of sin” – except these are now what make him appeal so much to us today. Bring it on.

Caravaggio’s rehabilitation came some time in the second decade of the 20th century, and today it seems inconceivable that his astonishing vitality and naturalism – just look at how Christ in Emmaus appears as a far more secular apparition than a holy one – should once have been denigrated. But as the exhibition Beyond Caravaggio at the National Gallery sets out to show, his influence during his lifetime, and in the short decades after his death in 1610, was profound. So profound that it changed the way artists looked and worked across Europe. His dramatic use of chiaroscuro was emulated by Caravaggists from Italy and Spain, France and the Netherlands. Indeed, though he never featured a burning candle in any of his paintings, such was the craze for depicting extremes of light and shadow that the flickering flames of a burning candle, casting its intense glow across the animated features of biblical figures and card-players and carousers alike, became a signature for many painters, including the French artist Georges de la Tour and several prominent Dutch and Flemish artists. Card-players and tricksters also followed on the heels of Caravaggio’s boisterous cardsharps, and here de la Tour also excelled.

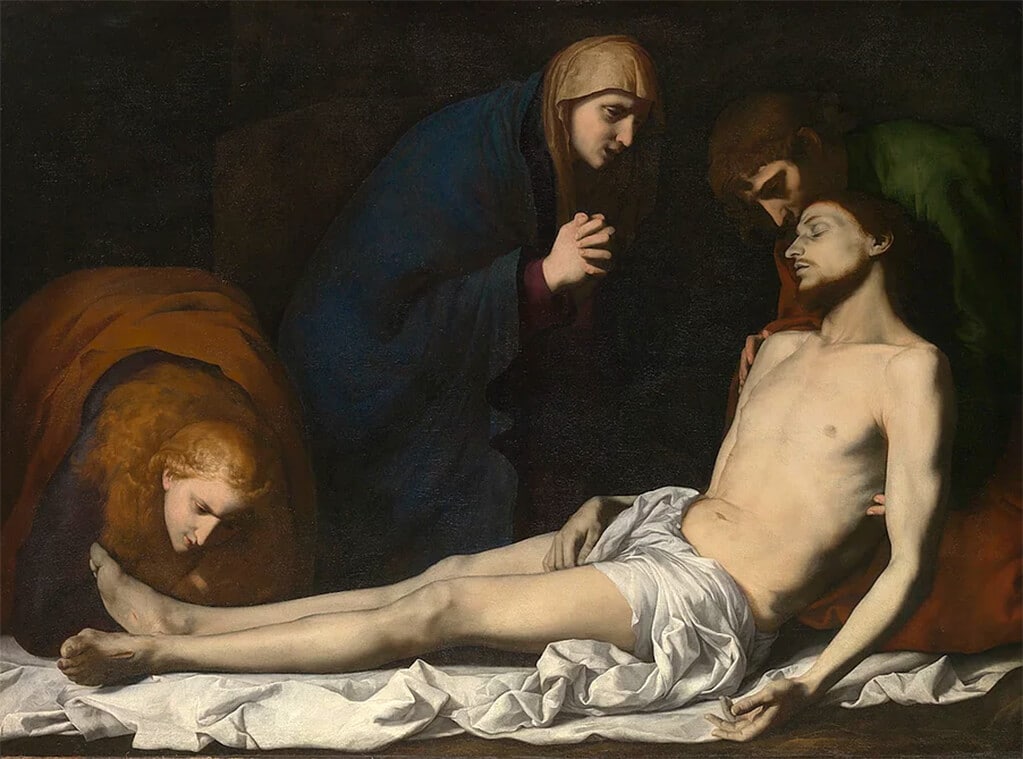

With a few exceptions, the exhibition confines itself to paintings borrowed from across the British Isles and Ireland, which limits its scope somewhat. But still there are a few stand-out paintings that illustrate how Caravaggio’s influence was absorbed and how the best were not simply imitators. Aside from the man himself (just six Caravaggios in the exhibition, three of which belong to the National Gallery collection), three paintings by Jusepe de Ribera should alone encourage a visit to the exhibition. Few artists painted soft, sagging flesh as convincingly as he did, and we see how as we scrutinise the aged, sinewy figures of Saints Onuphrius and Bartholomew. And his Lamentation over the Dead Christ, early 1620s, with its strange, wraith-like Magdalen and a Mary whose features look as if they’ve been carved in stone – aptly resembling a funereal carving – could well pass for a mystical 19th century Symbolist painting.

But essentially Caravaggio steals the show, and rather too easily. The sheer physicality and presence of his figures, their bodies pulling and pushing this way and that, pressing against the picture plane as well as against each other in compressed space, convinces us of their reality.

We need only compare two paintings from the National Gallery of Ireland to highlight Caravaggio’s runaway brilliance. Look at The Taking of Christ, 1602, next to Orazio Gentileschi’s David and Goliath, 1605-8, and you’ll discover just why Caravaggio astonishes with his realism. Caravaggio’s figures impact upon the objects around them. When flesh pushes against flesh the weight and compression of that contact feels real. But look, for instance, at David’s left foot on the billowing fabric in Gentileschi’s painting and one simply cannot get a sense of the weight and impact of that encounter. David half looks as if he’s floating in space, a bit like a cut-out figure. Caravaggio, meanwhile, does what he does with forceful vitality.