Reflecting on the significance of the last great age of the artist as hero and tortured genius

Abstract expressionism was not a movement, it was a phenomenon. With no defining style, mission or collective manifesto, it is, according to David Anfam, curator of the Royal Academy’s ambitious ‘Abstract Expressionism’ exhibition “the only word capacious enough to fit the bill”.

It’s a good word, denoting a spirit of place and time that brought together a cohort of heavy-drinking, saturnine artists. (In the catalogue, Anfam makes much of a gloomy collective mindset shouldering the burdens of the 20th century, and as grandiose as that may sound there’s certainly something in it.) These artists’ lives, friendships and rivalries have long since been mythologised, but their work was diverse enough to defy any meaningful definition.

It’s a phenomenon that undeniably speaks of the last great age of the artist as hero, as visionary, as tortured genius. Furthermore, these were artists preoccupied with the sublime. As such, it can be described as the last great hurrah of Romanticism. And it happened not in Europe but America. It was a home-grown phenomenon that was heavy in European influence, but was incontrovertibly American, and this itself is part of its resilient mythology.

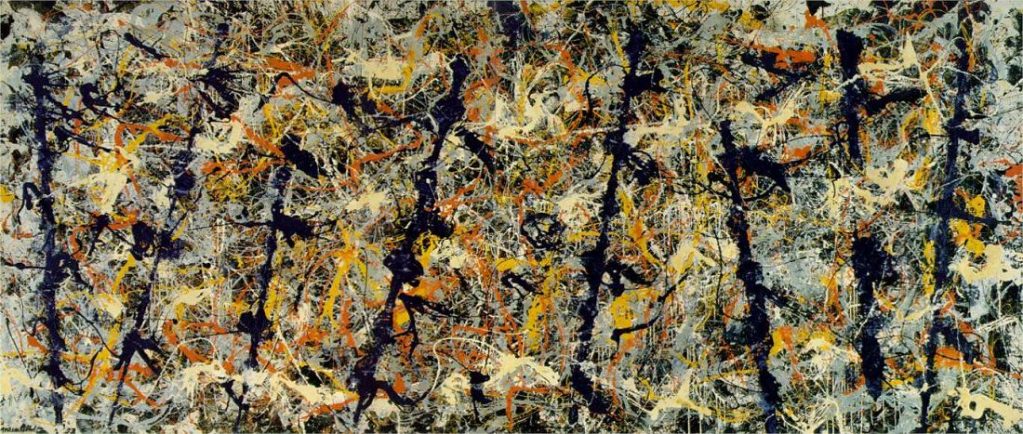

The names of the big-hitters, those whose mythic status, even today, remains surprisingly, defiantly undimmed, trip easily off the tongue, so embedded are they in the wider culture: Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning. They demand huge wall space and the exhibition devotes big rooms to each of them. Pollock’s monumental Mural (1943), which was commissioned by Peggy Guggenheim, the collector whose support essentially kickstarted Pollock’s career, faces the equally monumental Blue Poles (1952).

Inspired in part by Indian sand painting, Pollock dispensed with the easel and painted the 20ft-long Mural on the studio floor, engaging his body as if in a nimble ritual dance. Although essentially abstract, the painting’s dynamic structure and curving forms suggest a solemn and brooding procession of figures. By the time he painted Blue Poles he had become internationally famous as Jack the Dripper, flicking his brush at the canvas and pouring directly from a can. An intricately layered mesh of paint could suggest a whole cosmos, as indeed could Rothko’s shimmering horizontal bars, floating before the retina as if slightly detached from the canvas.

De Kooning on the other hand brings you right down to earth: his buxom, bug-eyed women, with their sharp Venus flytrap gnashers, are both terrifying and cartoonish, suggesting, as it does for all good Freudians, a castration complex – this while his broad, buttery wedges of paint exude uninhibited sensuality. What terrific tension contained within those brush strokes.

Walking through the exhibition, room after room, you almost feel the air vibrate, assailed as you are with so much kinetic energy. And the wow factor when you enter a huge gallery devoted to Clyfford Still, a painter who is not among those names who generally excite the wider public’s interest, leaves you astonished that you could ever have underrated him. Those ragged, jagged landslides of paint. This is epic painting of the modern sublime: grand, seductive, sensual and serious.

Then we have Arshile Gorky, Adolph Gottlieb, Barnett Newman, Robert Motherwell, Franz Kline, Janet Sobel, Lee Krasner, Philip Guston, Sam Francis, Joan Mitchell, even Helen Frankenthaler and Ad Reinhardt.

You could play a heated parlour game with who was and who strictly wasn’t an abstract expressionist, since some artists appear in the dead centre, some at the periphery, and some who are said to have provided a bridge between one thing and another thing, to which art historians have given other labels. Art history helps us understand the cultural dynamics and shifts underpinning what artists do, but for living painters there are no neat groupings – artists feed off each other, but they do not hunt in packs.

Does an exhibition such as this help us understand that any better, or merely add to the confusion? Sometimes, as here, it’s probably better to just think with your eyes. Certainly, it will take some deep and prolonged looking to see just how rich the paintings of Ad Reinhardt are, your eyes ever so slowly, incrementally, adjusting to find their black velvety surfaces actually containing grids of many subtle hues.

The Reinhardt paintings are extraordinary, and their legacy can be found in minimalism and conceptualism, even though they also reach much further back, to Malevich’s black square, and even though they weren’t after all the “last paintings” that anyone could paint, nor the first paintings about which that claim was made.

The legacy of abstract expressionism is, in fact, wide and surprising. Pollock’s nimble ‘action painting’ sparked a fascination in the actual process of creating work over that of the finished product. The repercussions of that have been huge, from happenings, to performance art to land art. Pollock is only a small part of that legacy, but he is a part of it all the same.

Aside from those legacies, what’s intriguing about this exhibition is not just those it includes under its capacious umbrella, but those it leaves out. Almost every room in the exhibition is punctuated by David Smith’s welded steel sculptures, and there’s a huge and impressive Louise Nevelson assemblage, made of objects all painted in matt black. But there’s no Alexander Calder, neither mobile nor stabile. And yet if there’s any sculptor who embodied urbane New York at the height of the abstract expressionist phenomena, it’s him.

But there’s no doubt that Calder would have disrupted the sombre mood of this exhibition. It’s simply instructive to see what is embraced and what is edged out in the careful shaping of a phenomenon.