Tate Britain's Queer British Art marks the 50th anniversary of the decriminalisation of homosexuality, but what a tame and closeted affair it is

Queer British Art is the title of an exhibition that reveals itself to be a tamely closeted affair. And, if you bother to read the smaller subheader giving the timespan covered you’ll see why. Despite its bold promise, this is a survey spanning an almost-century from 1861 to 1967 – so well before queer theory and the reclaiming of a word that, by the 20th century, was a pejorative for any male who was slightly effeminate.

Starting from the year that saw the abolition of the death penalty for sodomy, the exhibition marks the 50th anniversary of the decriminalisation of male homosexuality under the Sexual Offences Act (lesbianism was never criminalised). And that end date doesn’t just predate ‘queer’ as a word embracing a radical political identity, but also the word ‘gay’, which doesn’t really gain mainstream currency until as late as the early 70s (again, mainly for men).

This is why TV sitcoms and light entertainment programmes throughout that decade were full of ‘gay’ double entendres. Gay lives were so under the radar that even though gay camp was the defining part of Saturday night entertainment, heterosexual audiences could still labour under the illusion, remarkable though it now seems, that camp entertainers were simply straight men pushing the envelope a bit with titillating “What a gay day” catch phases. Four years after decriminalisation, sober audiences could watch a serious film about a middle-class straight-bi-gay ménage in John Schlesinger’s Sunday Bloody Sunday (in which the two male characters were denuded of any sign of camp), but popular light entertainment was still straight out of music hall.

So naturally, camp, musical hall, vaudeville, and theatre all play a part in this exhibition, under the gaily euphemistic heading ‘theatrical types’ – and no surprises that it’s women, again, that this title excludes. Men dressed as women and women as men were a 19th century music hall staple for family audiences, though clearly once trousers, shirts, and short hair became common female attire, there was little demand for women as male impersonators. Meanwhile, drag acts such as Danny La Rue, as we see here, could go on to become one of the most highly paid and visible entertainers of the 60s, all the while keeping their sexuality under wraps, years after it was ‘legal’ – or, as we’re gently reminded, ‘partially decriminalised.’ However bizarre the illusion – La Rue, for instance, was known for starting every show with his gruff navvy’s catchphrase, ‘Wotcha mates’ – heteronormativity had to be maintained.

Meanwhile, plays still came under the censorship of the Lord Chamberlain’s Office until the 1968 Theatres Act abolished the censor. And it’s the ephemera that comes with all these details, the plays that escaped the cuts or which were performed uncensored in private clubs, the real lives of those depicted in largely dull, forgotten portraits, the details of the masquerades that were maintained for the sake of one’s standing in society (though many seemed to be surprisingly open and unfettered) that prove absorbing; that is, it’s the reading between the pictures and the photos and the artefacts that largely detains you.

You’ll find that Robert Harper Pennington’s full-length portrait of Oscar Wilde, c. 1881, isn’t half as absorbing as the story of its commission and its sorry fate after Wilde’s disgrace. Nor are the stilted pre-Raphaelite paintings of androgynous figures by Simeon Solomon, an artist who suffered a similar fate to Wilde and who died in disgrace – in Solomon’s case he was arrested in a public lavatory for ‘attempted buggery’. Though even here the law has a human face. Duncan Grant’s portrait of PC Harry Daley, portrayed in his buttoned-up uniform and helmet, is identified as E.M. Forster’s sometime casual lover, who later wrote a memoir detailing his exploits on both sides of the law. Forster had a thing for working-class bobbies, and indeed the sexually fetishised nature of both class and race are coyly hinted at.

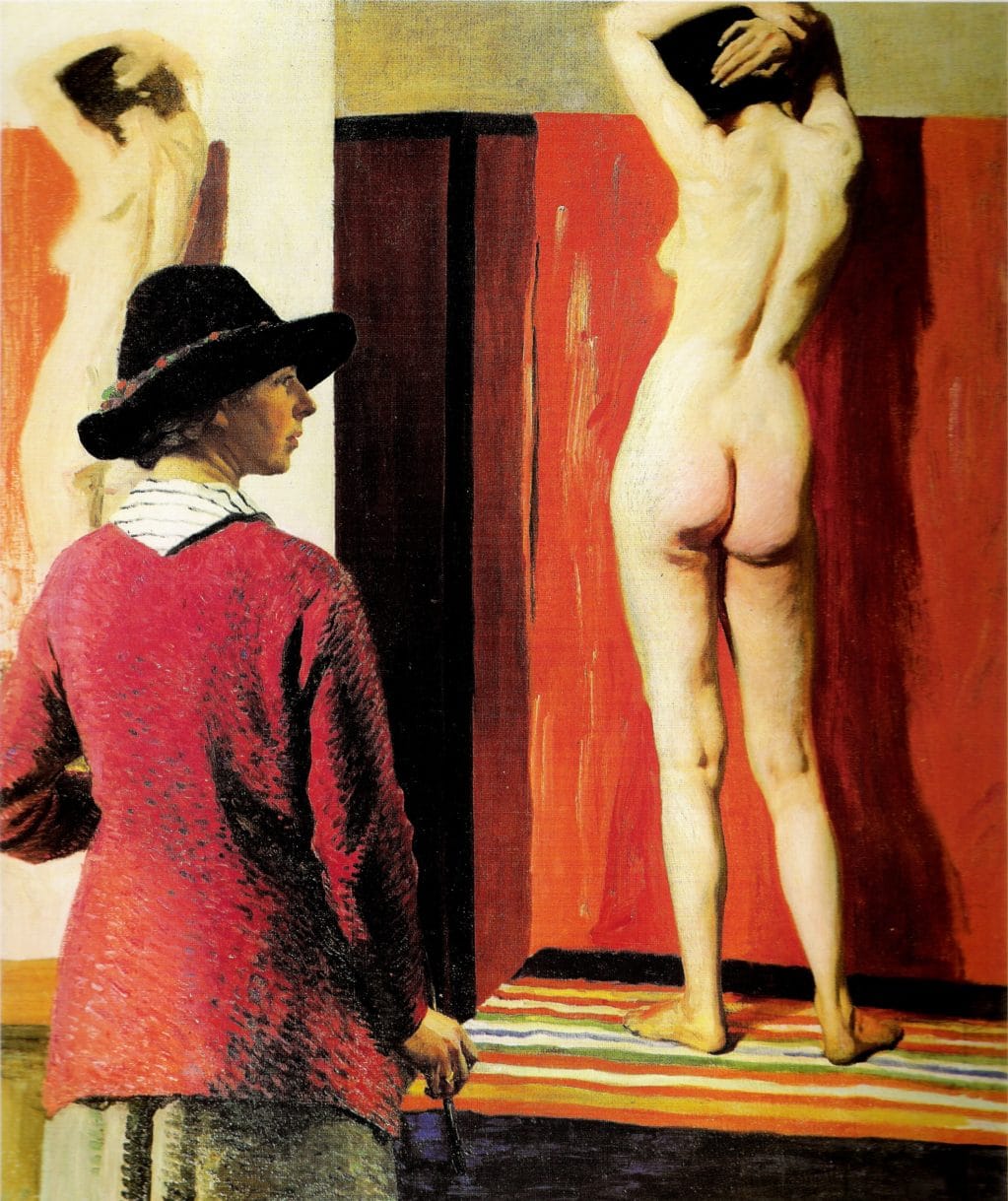

But there’s a difference between an exhibition that shows work by artists who are gay or queer or lesbian, and a thematic show that illustrates its subject or opens up a way of understanding its subject through mainly visual means. The former needs a lot more framing and scaffolding, and this is an exhibition that manages to work largely because of this framing – though it also chooses to muddy the waters by including artists who don’t fit under any queer labels at all. The heterosexual (probably) and married Laura Knight pops up, though of course, she’s also an artist who punctured ‘gender norms’, albeit in a much broader sense, that is, by simply being a woman artist breaking the mould by painting female nudes in the first half of the 20th century. However, there’s nothing really ‘gender fluid’ about this.

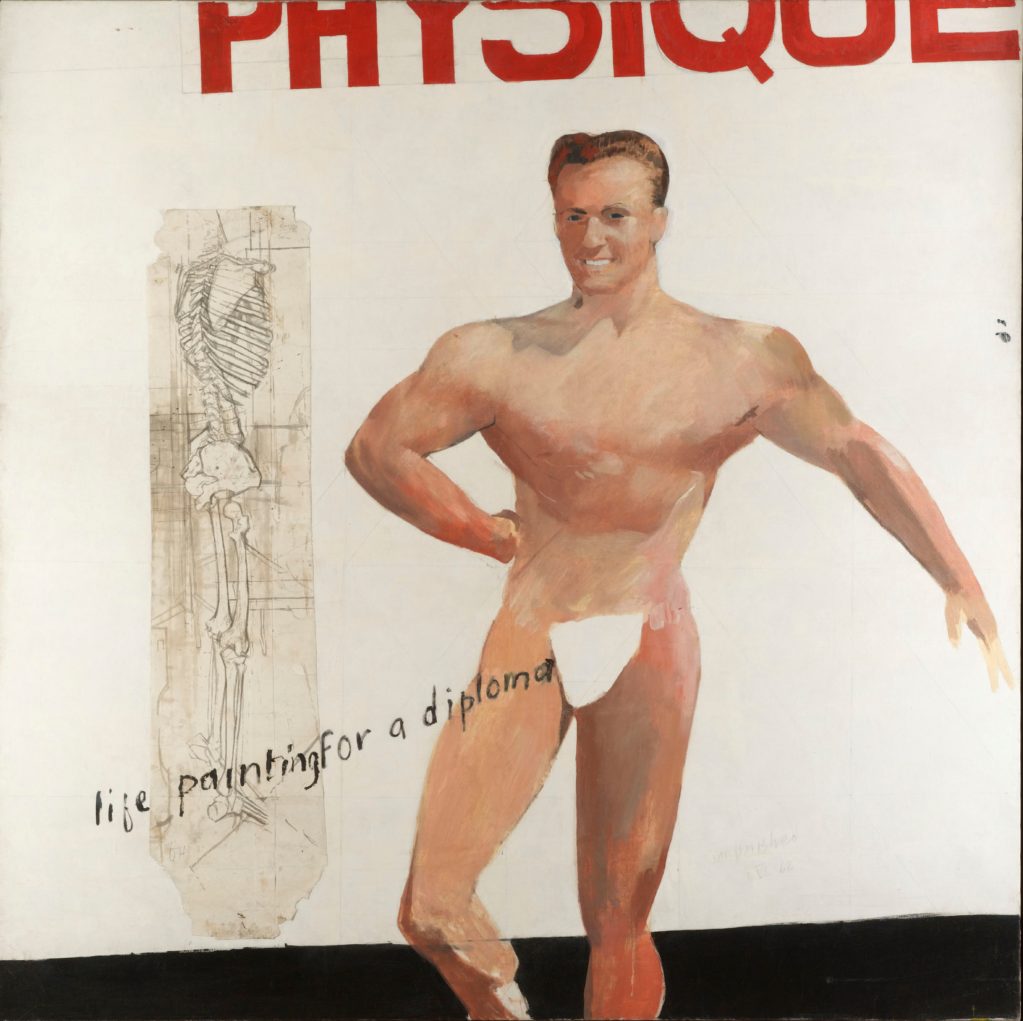

In the end, one’s left with the impression that she’s included because there simply aren’t enough women in this show – so thank heaven’s for the overworked Bloomsbury Set and their associates for making up the numbers, I guess. Even so, one can have too many genteel drawing room paintings. And that the exhibition ends with its two biggest names, Hockney and Bacon, in a kind of showdown, underlines how much its skewed towards the male presence.

One could wish for any number of different exhibitions, more exciting than this one, to celebrate a half a century of increasing visibility. One from 1967 to now might have served its title better. Or one less willing to dilute its subject. Some private, graphically erotic drawings by Duncan Grant, perhaps, shows another alternative. One thinks of the private, erotic drawings and paintings of artists such as Turner or Rodin which have long fascinated curators. How much more intriguing it would it be to explore the more intimate nature of queer desire that such a possibility presents. Another time, perhaps, and in a smaller space.