The Royal Academy's new show of depression-era American art is a curatorial triumph

It was, naturally, the best of times, the worst of times; the epoch of belief and the epoch of incredulity. And so forth. This is America caught between the dream and the crash, between hope and hopelessness, and between two world wars. It’s the America of jazz and swing, of bodies spilling out of theatres and bars (during and post prohibition), of Manhattan sidewalks swelling with heat, and of the Harlem Renaissance.

It’s the America of apple pie and thanksgiving, of the foundation myths of the founding fathers, as well as the America of the dustbowl, of Jim Crow, of the lynching rope, of the fear of union power, and of the anxiety of loneliness in crowds.

Here is the land of the free and the land of the oppressed, contradictory and multitudinous. And if you can capture all that in forty-five paintings, you’re onto a winner.

The Royal Academy’s America After the Fall: Painting in the 1930s is a deeply fascinating exhibition. It is an exhibition expressing a concatenation of ideas in visual form, where the visual forms speak strongly and on their own terms. It lets you know that American painting, in the decade or so before the anointing of abstract expressionism as an all-American affair, owed no allegiance to any one style and sang with multiple voices and accents.

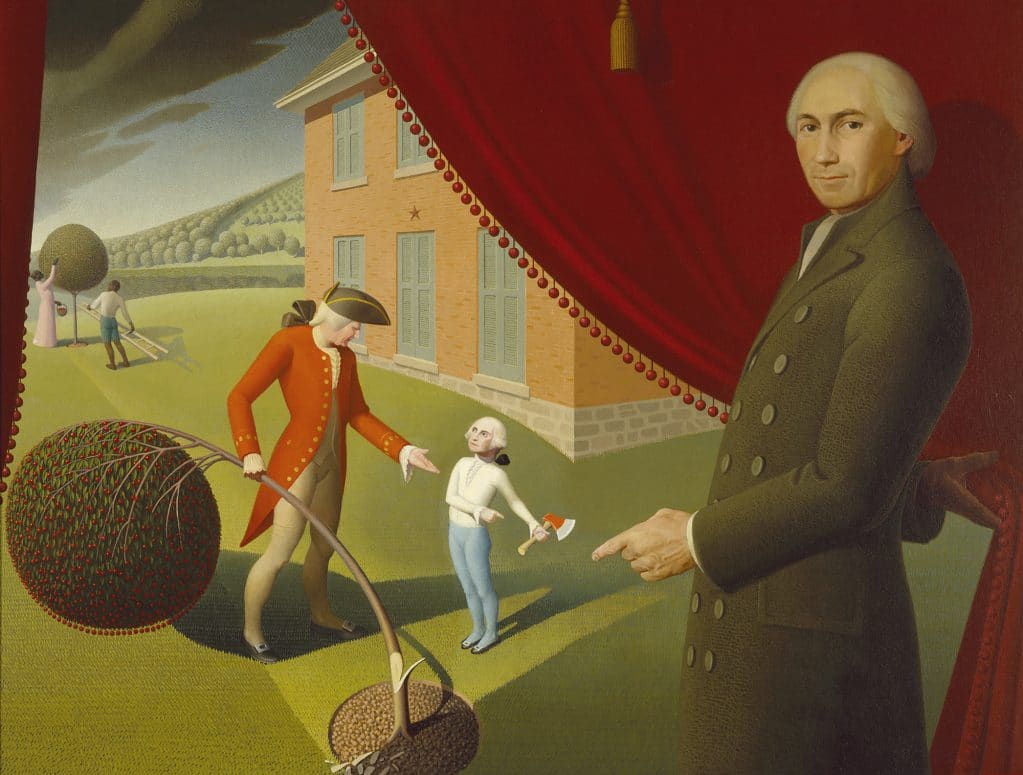

Here you’ll find all the European -isms to date, plus that very particular folky primitivism that harks back to America’s colonial past with its starchy, faintly comic air. This was a style that inflected much of the work of the Regionalists – including Iowan artist Grant Wood, a painter who looked to America’s past, to its provincial rural character and to its foundational myths. His subjects include the heroic midnight ride of Paul Revere which triggered the American Revolution – there he is, if you can spot him, a teeny figure on his rocking horse – , and the young George Washington – actually more of a version of Gilbert Stuart’s famous portrait but in comic miniature – enacting, with a nod and a wink, an apocryphal episode in the life as an example of the fledging president’s courageous honesty.

Wood has the largest number of paintings in this exhibition, though blessedly its character doesn’t dominate. Chicago and New York may have pioneered modernism on the streets with their cladded steel-framed skyscrapers several decades earlier, but in that most traditional of artistic forms, easel painting, really not so much.

This is hardly to say that the thirties didn’t produce some very significant American painting, with work that gets to the heart of America’s inherent contradictions. An enduring example is Wood’s most famous, here given a wall to itself – those two faintly creepy puritans in American Gothic, a painting mildly satirising the parochialism of Midwest folk. It’s the first time the painting has been loaned outside North America, as it is with many of these paintings.

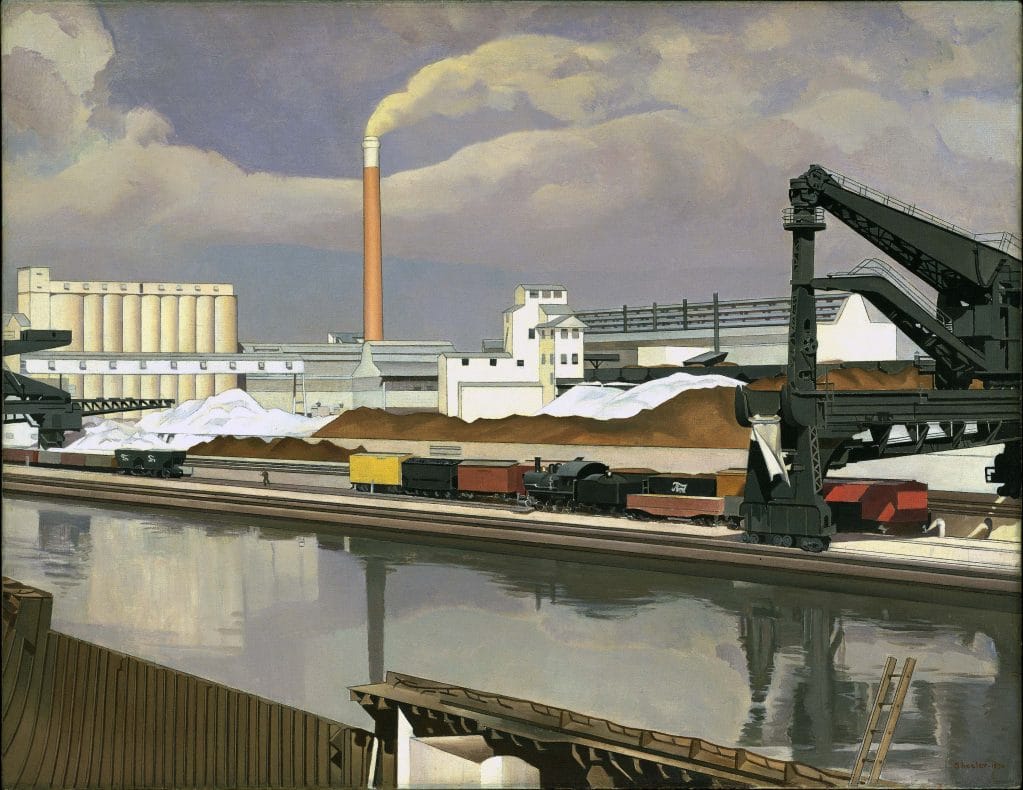

Here you’ll find the neglected Arthur Dove, an early inspiration for Georgia O’Keefe (O’Keefe herself is represented by a painting of cow skull). His abstractions remain a forgotten pioneering force in American art. In contrast, the coolly detached Precisionism of Charles Sheeler’s industrial landscapes, with one work featuring a gigantic machine that looks like a missile and makes insignificant insects out of humans. There’s Thomas Hart Benton’s weary but industrious cotton pickers; Joe Jones’s American Justice, featuring a demonic huddle of KKK hoods, a burning house, and the figure of a prone semi-naked black woman under a noose slung over a tree branch, under which a dog looks up plaintively.

A packet of Wrigley’s spearmint gum floats in front of skyscrapers in Charles Green Shaw’s homage to capitalism, which started as a photomontaged advertising image and is now rendered as a precursor to Warhol facsimiles of American brands. In Aaron Douglas’s Aspiration, a silhouette of a trio of African-Americans, newly liberated from their chains and evidently symbolising the muses of science, literature, and the arts, gaze with longing at a shimmering modern acropolis in the distance.

In the steaming hot city, sex naturally makes an appearance. In Paul Cadmus’s The Fleet’s In!, homosexual desire is daringly hinted at in a captivating comic scenario featuring a bunch of drunken sailors and some good-time girls. Amid the busy scene, a handsome dandy with carefully plucked brows offers a cigarette to a rough-looking pug-nosed sailor, who evidently can’t wait for some of the action. Meanwhile, the lonely scenarios of Edward Hopper hint at the absence of sex in the faded glamour of a near-empty movie theatre, a lone usherette lost in her thoughts.

There are some big names, too, in often surprising early guises: Philip Guston’s tondo painting, Bombardment, is an imagined depiction of the air-bombing at Guernica, painted in the year Picasso was busy with his more famous version. Foreshortened bodies fly, flail and tumble in artful arrangement. It’s muscular socialist realist agit-prop, and reminds you a bit of Peter Kennard. Jackson Pollock is another: here in frenzied semi-abstraction are the tangled body parts of human and horse, a closer if perhaps unconscious rendition of Picasso’s great mural painting. And for a different mood entirely, there’s Stuart Davis with a jaunty arrangement of gas pumps, mail box, skyscrapers, a darling Parisian café and other pleasing objects in New York – Paris No. 3, 1931.

This exhibition, brilliantly curated by Chicago Art Institute’s Judith A. Barter, would be a triumph on its own. But it’s a stroke of genius to run it concurrently with Revolution: Russian Art 1917-1932, a vast, fascinating and sprawling exhibition that downplays the extraordinary radicalism of the Soviet avant-garde in order to give a broader, more complex historical overview. Though American art of the thirties was still struggling to find a radical language of its own, political and social radicalism was very much in the air. Artists absorbed the life and energy around them.