A museum acknowledges an artist it features was a serial sexual abuser. Why is it so rare for the art world to put work in this kind of context?

Just how true is the following statement: an artist’s work should have value in its own right, no matter what sort of life the artist led, and even if they have damaged or hurt others? Perhaps we might put the answer on a sliding scale, for don’t we as a culture, hold it to be true when it comes to some artists, but not others?

Tate Britain’s current Queer British Art exhibition, which includes the work of the writer and collagist Kenneth Halliwell, is just one of a recent spate of exhibitions and film screenings that might prompt you to ask this question afresh. In 1967, in the tiny one-room flat the couple shared in north London, Halliwell bludgeoned his partner, the playwright Joe Orton, to death, before ending his own life. Clinically depressed, isolated and increasingly fearful of losing Orton, who was clearly tiring of him by then, he finally, as we’re pithily inclined to put it, ‘snapped’. Halliwell left a suicide note simply saying all would be explained in Orton’s diaries, “especially the latter part”.

Halliwell is generally viewed sympathetically by writers and filmmakers who’ve documented his and Orton’s life together. The inclusion of one of Halliwell’s solo collages at Tate Britain appears to have invited no controversy at all. In fact, it’s Orton’s behaviour that’s hinted as being selfish or cruelly off-hand, and we’re often reminded both of Orton’s promiscuity and his rapid success as factors in driving Halliwell to such a desperate action. We’re given mitigating psychological complexities that aren’t always afforded when terrible crimes are committed, but I also wonder if, at its heart, there’s an unstated sense here of Orton’s culpability in his own murder.

Clearly it’s tempting to ask, would this be the case had Orton been female? It’s interesting to ponder how differently institutions today might view the power dynamics if that relationship had been a heterosexual one; how eager might they be to establish Halliwell as an artist in his own right alongside his female victim?

Outline of a dispute

One artist whose work is of far greater importance than Halliwell’s is the minimalist sculptor Carl Andre. He is still alive and has never been short of major museum shows. Andre was married to the artist Ana Mendieta until her death in 1985, in what many still regard as suspicious circumstances. Mendieta fell to her death from the couple’s high-rise apartment in New York, and in 1988 Andre was acquitted of second-degree murder.

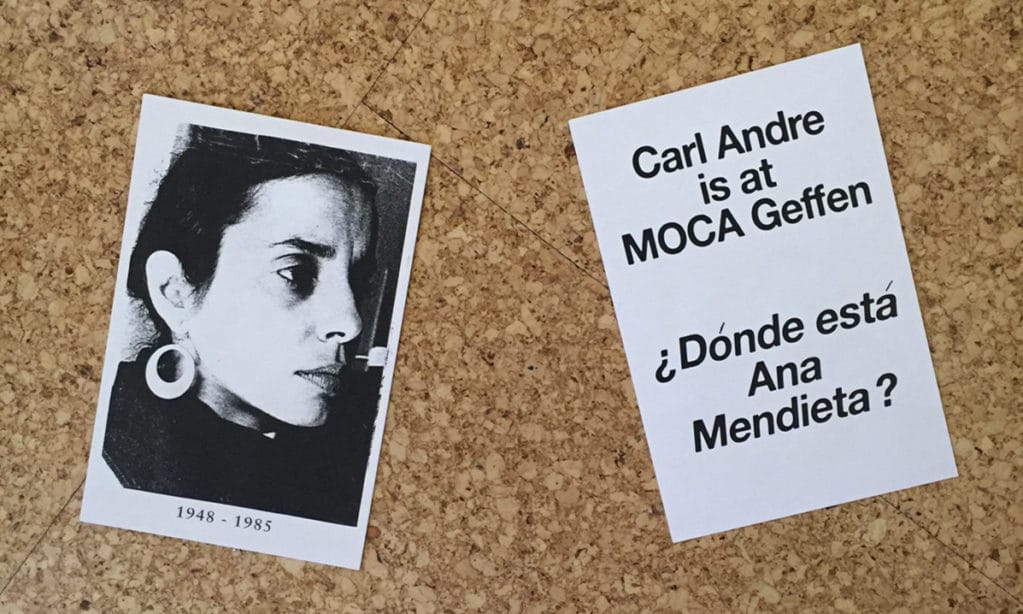

But despite the acquittal, Andre’s exhibitions have been dogged by protests by feminist activists and fellow artists. One performative protest saw demonstrators pour and smear red paint outside a gallery where his work was being shown. This was both an homage to Mendieta’s powerful performances in which she smeared herself and her surroundings with blood and a reminder of the violence of her death. And just last month, those attending a private view of Andre’s current show at the Geffen Contemporary in Los Angeles – an outline of the Museum of Contemporary Art (Moca) – were greeted with a carpet of fabric laid at the museum’s entrance, on which rows of candles were placed and where outlines of bodies had been painted. Once again this was strongly reminiscent of the ritualistic aspects of Mendieta’s own body-imprint earth works, as well as a an imitation of police forensics. In addition, postcards were handed out with an image of Mendieta accompanied by the text: “Carl Andre is at Moca Geffen. ¿Dónde está Ana Mendieta?” (Where is Ana Mendieta?)

The postcard that was distributed at the MOCA protest during the opening of the Carl Andre exhibition

These performative protests manage to go beyond the question of Andre’s guilt or innocence to address the very art institutes whose values they’re holding up to question. They demonstrate a gathering disquiet and sensitivity around the way Mendieta’s work was long neglected after her death, in contrast to the way Andre’s work continued to be lauded without so much as a blink.

The protests also make very clear how art and an artist’s biography aren’t so easily separated. How we negotiate the two can be quite complex, particularly if it’s an artist that the establishment culture has long invested in and simply can’t afford to sacrifice as a valued commodity. Mendieta was, for a long time, simply dispensable to a culture clearly not invested in art by women.

Putting in context

One institution that has been prepared to ask how an artist’s life does indeed affect the way we receive the work, is the Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft. This small museum in East Sussex in the south of England is dedicated to the work of the 20th Century sculptor, typeface designer and printmaker Eric Gill and his circle. Gill’s life as a serial sexual abuser of his two pubescent daughters was first documented in Fiona MacCarthy’s 1989 biography of the artist, as was his incestuous relationship with his sister.

But although this information has been in the public realm for almost 30 years no previous exhibition of the artist’s work has confronted it, seeing it as neither necessary nor relevant. However, it seems clear that curators shy away from biography only when it’s perceived to be too problematic, since any inclusion will almost inevitably demand more than a cursory mention – unless, of course, the artist has been dead too long for us to be fazed. Just think, for instance, how many times Caravaggio, a known murderer and rumoured pederast, is mentioned when defending the principle of separating the artist from their work.

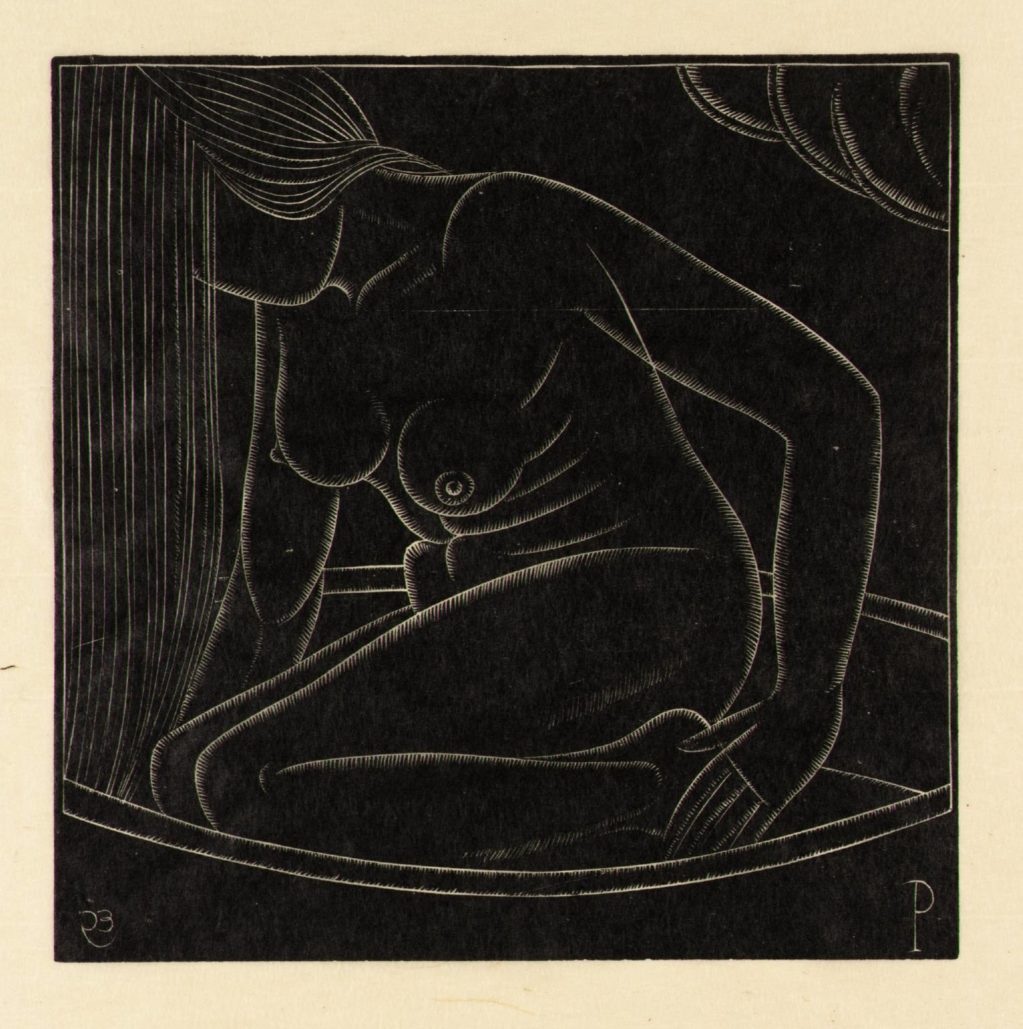

When the Ditchling Museum re-opened in 2013 after a major refurbishment, none of Gill’s abuses were addressed, though of course anyone who knew about them couldn’t help but be reminded when confronted by, for instance, a sensual and intimate drawing of his young daughter Petra in the bath. What you saw was altered by what you knew.

None of that demands that the work be censored. But context probably does matter. Gill carved many monuments and relief sculptures throughout his life, including the figures of Prospero and Ariel on the exterior of the BBC’s old Broadcasting House headquarters. He was also a practicing Catholic, and carved religious icons and altarpieces for churches and cathedrals throughout the UK, including his impressive Stations of the Cross for Westminster Cathedral. When MacCarthy’s book came out, there was a concerted campaign to rid the cathedral of this celebrated work. One might imagine the mixed feelings of some worshippers when confronted with these ‘inappropriate’ holy images, which are there, after all, to offer moral guidance, sustenance and solace. But it seems most have now come to terms with these works.

The Ditchling museum itself has now had a radical rethink: central to their current exhibition, Eric Gill: The Body, is the question of how knowledge of Gill’s abusive behaviour affects our impressions of his work, some of which is sexually and anatomically explicit. When organising the exhibition, the museum took advice from several charities who work with sexual abuse survivors.

Gill died in 1940, but we think today of others in the public eye and the continued controversy that surrounds them. Film directors Roman Polanski and Woody Allen come to mind and the utterly polarised reactions they both elicit, though both continue to work as productively as ever.

And of course, it’s never just about the work. What we do when we celebrate an artist is often to bolster the myth of their life. We do this with Caravaggio exactly because we’re fascinated by his earthy and seductive ‘bad boy’ image. That roughness and that sexuality makes him feel alive to us and incredibly modern, as alive as the figures in his paintings. And we do this with Oscar Wilde, who we celebrate today for exactly those things that ensured his condemnation in life.