This year's exhibition at Tate Britain is dominated by film from all four nominees – Forensic Architecture, Naeem Mohaiemen, Charlotte Prodger and Luke Willis Thompson. It's a strong shortlist and a compelling exhibition

If I tell you that you’re in for a long haul at this year’s Turner Prize, please know that I’m not trying to frighten you off. The four nominated artists all work in film and video, with one artist presenting two films with a running time of around one and a half hours each, so you’ve already clocked up three if you stay for the duration of Naeem Mohaiemen’s contribution, and it’s highly recommended that you do.

Mohaiemen was born in London, but grew up in Dhaka, Bangladesh. He has also spent long periods in the U.S, where he is currently studying for a Ph.D in anthropology. I mention this only because it’s clearly pertinent to his work. Two Meetings and a Funeral is a slowly ruminating film, playing on a huge triple split-screen and focusing on the emergence of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) at the height of the cold war.

Early member states included India, Yugoslavia, Cuba (it was formed just a year before the Cuban missile crisis), Iran and Algeria, along with other nations now known as the Global South. They were for sovereignty and independence, and against colonial rule and neo-colonialism, meaning the hegemonic powers of the United States and the Soviet Union.

The title is a nod to Richard Curtis, but it’s more like Adam Curtis on downtime. There’s lots of lingering archive footage of UN meetings and NAM meetings and long shots of UN corridors, with Marxist historian Vijay Prashad appointed to look over an era that begins in 1957 with the Russians sending Sputnik into orbit, an event whose legacy, we learn, lives on in the number of children in India, now in their sixties, named after the satellite.

I’m not sure this is selling it and it’s true there have been a few sub-Curtis films doing the international art circuit for some time, but Mohaieman is a far more interesting filmmaker and a far more imaginative documentarist (though I’m sure he wouldn’t call himself that) than most. His second film, however, is in fact fiction, loosely based on a story of his father losing his passport and being stranded in an airport for nine days.

Tripoli Cancelled is wonderful, playful, sad and beautifully acted and written. Clean-shaven and dressed in an elegant linen suit, a man marks time all alone at an abandoned airport where he’s been stranded for over 10 years. He maintains appearances, makes urgent calls to a loved one on a disconnected phone, reads aloud from Watership Down to a child conjured from memory, double role plays in front of a mirror, laughs, a little crazily, and longingly caresses a mannequin dressed as an air stewardess.

In the end he finds himself dancing to Boney M – what else can he do but escape into himself? He is stranded in perpetuity, literally and between metaphorical borders, and an airport after all, being both mundane and eternally strange, evokes all kinds of longings and feelings of loss and existential abandonment.

Mohaieman is such a strong contender that I’d still be been rooting for Forensic Architecture if he hadn’t muscled in. Their exhibition at the ICA, just one of the exhibitions they were nominated for, was a revelation. Their work has also been seen recently in the UK through their collaborations with Beirut-based artist Lawrence Abu Hamdan, who works with sound waves and who’s sonically mapped the locations of Saydnaya prison wherein blindfolded survivors of torture were able to corroborate their experiences.

A ‘counter-forensic’ agency which investigates state and corporate violence, Forensic Architecture is based at Goldsmiths University and has worked with the United Nations and Amnesty International as well as other human rights organisations. Their work is complicated and produces impressive real-world results which are remarkably amenable to multi-layered, multi-media gallery displays incorporating 3D models, digital mapping, newspaper reports and witness testimonies.

I don’t think there’s much point arguing whether it’s art, but the organisation, which was set up by founding director Eyal Weizman in 2010, does utilise the expertise of artists, filmmakers and architects. So you can say the artists involved are simply expanding what they do in terms of their practice, since art as a category is expansive enough.

Here the focus is on one investigation: attempts by Israeli police, on the night of a raid to dismantle the homes of Bedouin communities, to frame a Palestinian – who they’d already shot and killed in the split second it took for his car to roll over a body – for the murder of a policeman. The events on the ground are clamorous and confusing, yet the investigation – alongside claims and counter statements by politicians and reporters after the event – unfolds with meticulous precision.

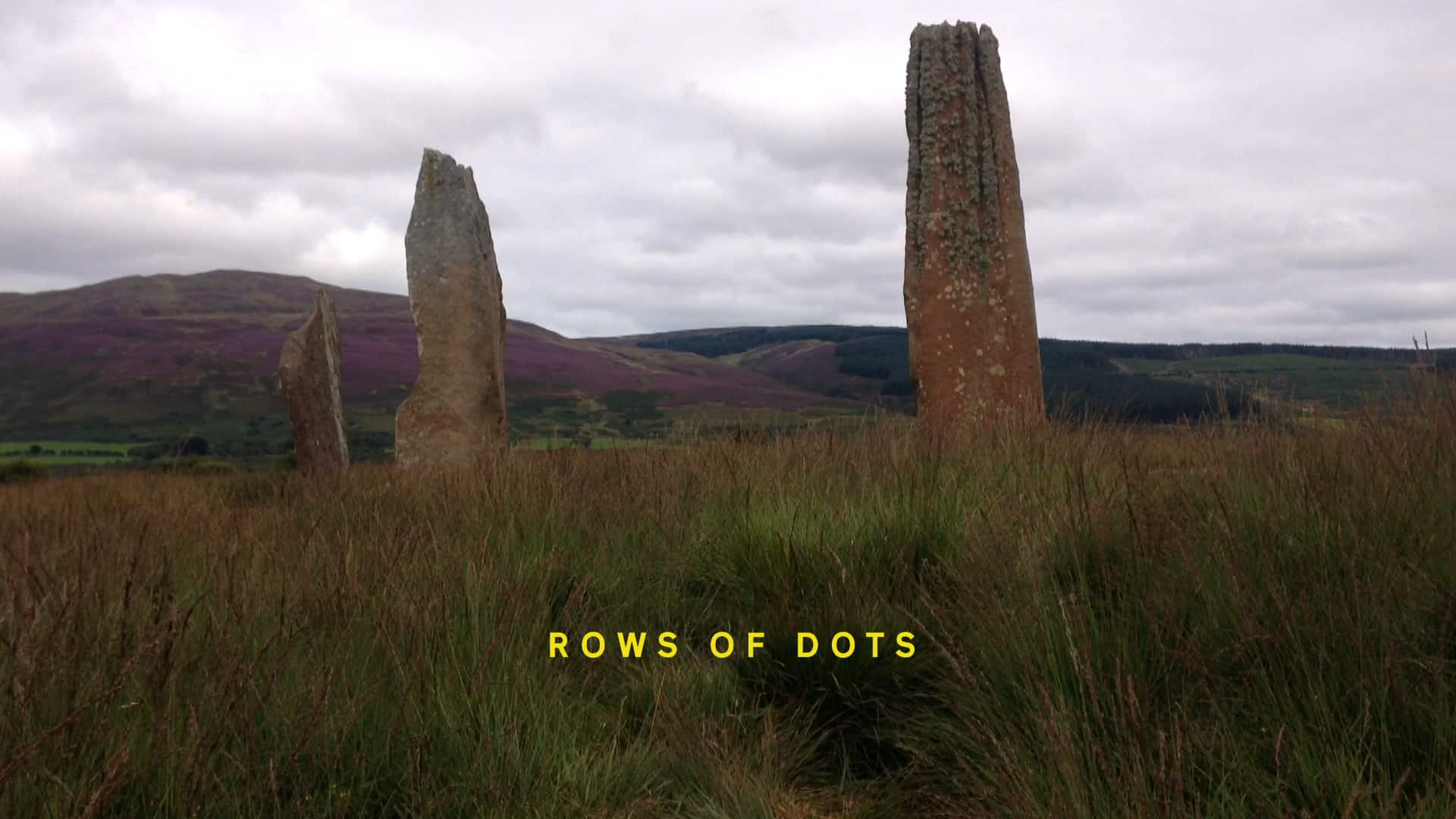

Absorbing at quite a different pace is Charlotte Prodger’s Bridgit, an off-beat and quietly mesmerising film that includes an account of the artist’s lesbian coming out, fond recollections of Julian Cope and his interest in Celtic stone circles, and the Celtic goddesses the artist was beholden to growing up in Aberdeenshire. It’s far more prosaically filmed (Prodger films with her smart phone) than Luke Willis Thompson’s portrait films of his black subjects, but leaves a residue of feeling and memory that outlasts anything in Thompson’s work, even while you’re in the midst of it.

Filmed on celluloid, his almost still framing offers us the scrutiny of a portrait in close-up of the close relatives of victims killed by police, the most recent victim being Philando Castile. Castile had been pulled over by police with his four-year-old daughter and girlfriend, Diamond Reynolds, in the car. Reynolds live-posted on Facebook as the scene unfolded, provoking a huge media response. Here, unlike the two young men in Thompson’s series, she never looks directly at the camera. At points she appears to be soundlessly reciting, maybe a song, or an incantation.

Thompson’s aesthetic can be compared to Tacita Dean’s – its grainy texture, its stark, beautiful lighting, and the rolls of film running through its noisy, stand-up reel. His best piece takes as its subject Donald Rodney’s tiny house made from the late artist’s skin, when he was sick with sickle cell anaemia. The translucent walls of this fragile sculpture glow with the light that penetrates its porous surface.

Something good has happened to the Turner Prize since Tate Britain’s director Alex Farquharson took over in 2015, and much of it has to do with taking simple practical measures in the way film work is installed: sound-proofing, bigger screens, properly darkened spaces and even comfortable seats. It’s as if film as a unique medium has only now just been recognised in the galleries of Tate Britain, and it’s about respecting the work. This helps the viewer, though mostly it helps the work.

Last year saw an exciting shortlist that corresponded with ditching the prize’s upper age limit. This year is another strong shortlist, though I’ll probably remain unconvinced by Thompson.