Featuring artists Hurvin Anderson, Andrea Buttner, Lubaina Himid, and Rosalind Nashashibi, this year's Turner Prize exhibition in Hull showcases strong and exciting work

There are bad years – often crashingly bad – and there are good years, but when was the last great year? It may be no accident that now the Turner Prize rules have changed and got rid of the upper age limit, we have a particularly strong year.

And it’s not just the line-up. Joint curators George Vasey and Sacha Craddock have done a brilliant job discreetly integrating the exhibition to the permanent historical collection of the Ferens Art Gallery in Hull, a gentle reminder for those who remain perennially astonished by it, that contemporary art has always been a part of art’s bigger story. It’s certainly an encouraging sign.

Lubaina Himid has had an incredible year. The 63-year-old artist, who was a powerhouse within the British Black Arts Movement during the 1980s but little known outside it, has been nominated for not one but two solo exhibitions in the UK (artists, as is the case with this year’s line-up, can be nominated for exhibitions outside the UK): one at Modern Art Oxford, the other at Bristol’s Spike Island gallery. She also featured in a superb travelling survey of pioneering Black British artists which opened at Nottingham Contemporary.

Few, apart perhaps from last year’s youthful Turner Prize winner Helen Marten, who at 30 was the youngest winner in the award’s 33-year history, have had such exposure in such a short span of time. Himid – the oldest nominee in the prize’s history – is having her moment and has been mooted as the favourite to win.

Though I don’t think she will take the prize, her work has never looked so good, and the judges this year will take the exhibition into consideration when choosing the winner. This is another rule change for the better, since it makes transparent what was always an unofficial process.

However, some might seriously quibble that one of her installations was made way back in 1986, when Marten was just one, Margaret Thatcher was at her height, and the Left were marching against Apartheid in South Africa and joining in a chorus of ‘Free Nelson Mandela’. It could be argued that this goes against the spirit of the prize, which should be all about what an artist is doing now. Yet since Himid was nominated for work spanning her entire career it seems entirely fair to include one of her works from this period.

A Fashionable Marriage is a figurative installation riffing on Hogarth’s series of narrative and wittily moralising paintings Marriage A-la-Mode. The piece, a theatrical tableau marrying grotesque figures representing the white slave-owning aristocracy with those who benefit from exploited wealth today, and black figures representing the black presence in the UK both during the days of slavery and the present, is now, aptly, set upon a low stage.

A fashionably dressed young black woman – if white, she might have been called a ‘career woman’ back in the 1980s – sits on a sofa looking awkward and askance at a lairy white guest crashing into her space. Behind her is a column plastered with newspaper cut-outs, with one headline referring to South African president PW Botha, another declaring sanctions to be ‘ineffective and immoral.’ In the middle presides a flamboyant figure with a collaged head made up of fragments of Margaret Thatcher’s face, and on one boxy shoulder we read ‘staunch supporter of apartheid.’

A Fashionable Marriage is a detailed and immersive work that feels surprisingly current and freshly resonant, certainly when younger artists are once again making work that, however obliquely, embraces the political. We find, for instance, thematic links particularly with Rosalind Nashashibi, whose film Electrical Gaza is one of two films in the exhibition. The other is Nashashibi’s Vivian’s Garden, which features a middle-aged Swiss artist and her elderly artist mother in their Guatemalan home surrounded by servants and dogs.

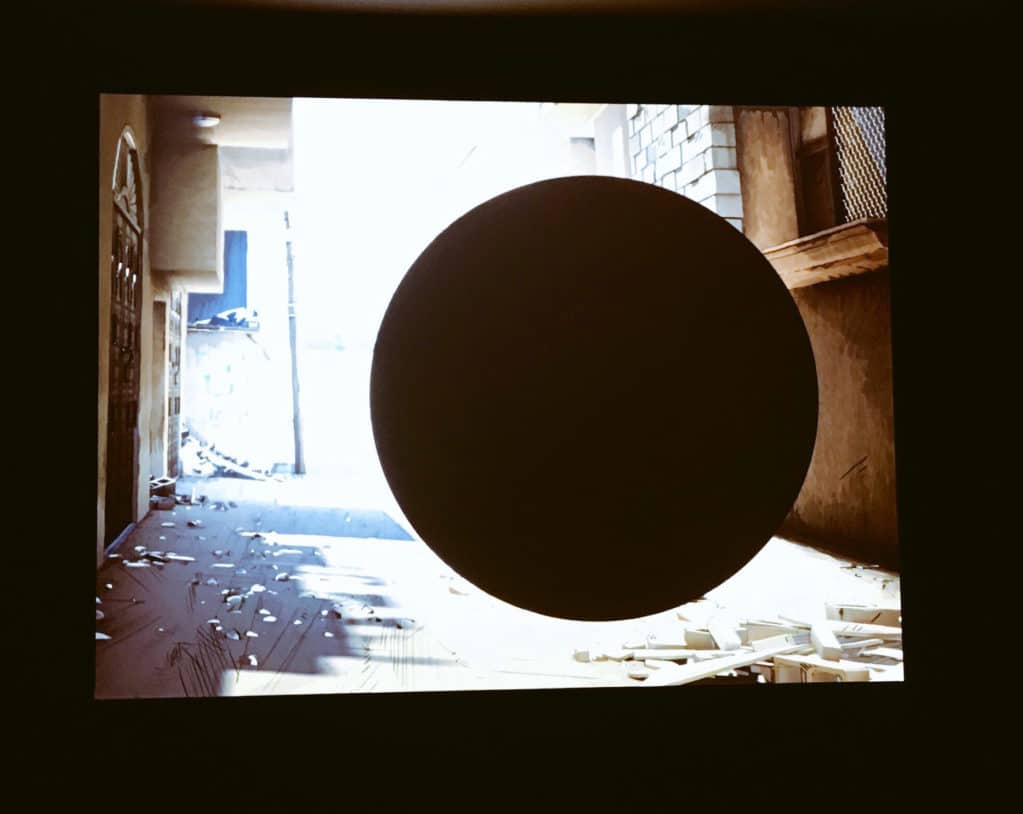

Both the films are visually arresting, slow and meditative, yet their fragmentary nature and lack of ostensible narrative only heightens their quiet power. Nashashibi filmed Electrical Gaza in the Gaza strip in the summer of 2014, just days before Israel’s bombardment. We become engrossed in the everyday life of residents.

However, on the advice of the British Foreign Office, Nashishibi had to abandon filming when it became too dangerous to stay. Animation was added to apparently fill in the gaps, but it’s more to suggest her abrupt departure. In one sequence, a big black circle expands on the screen, a portent for the violence ahead.

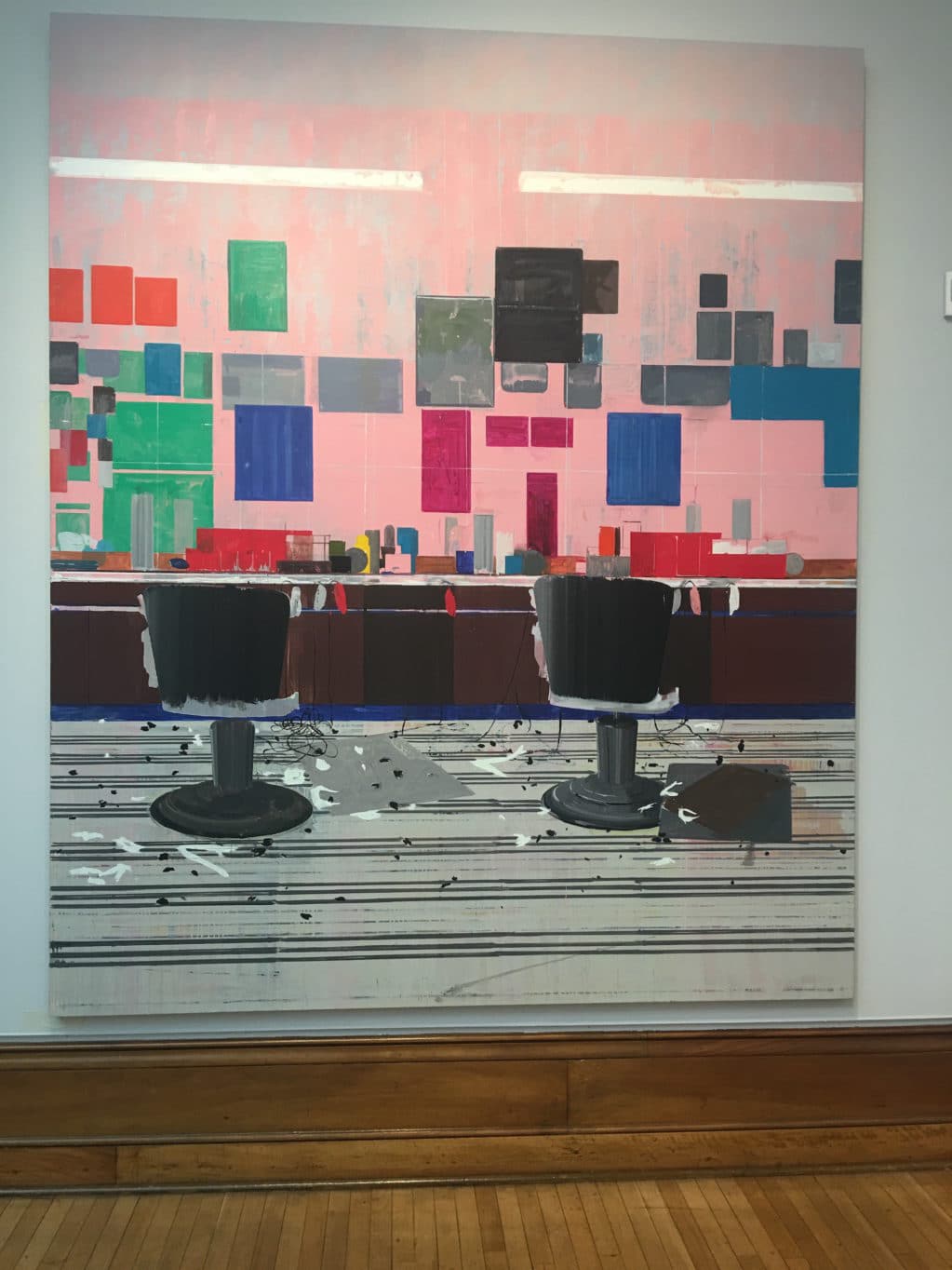

The exhibition feels very much part of wider political discourses. The other over-50 artist, the painter Hurvin Anderson, asks Is it Okay to be Black? It’s the title of a painting which includes the heads of Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. His paintings are astonishing, as is his use of colour. Imagine a cross between Peter Doig and William Coldstream, throw in some Impressionism and a few abstract grids built up with veils of watery paint , and you’re almost there. His extraordinary paintings of black barber shops tap into a particularly rich heritage.

Finally, German-born Andrea Büttner presents a body of work that includes large woodcut prints, abstract prints made by touching the screen of a mobile phone with greasy fingerprints, and the appropriation of a text-photo installation featuring the words of philosopher Simone Weil. The last isn’t her own work, but taps into her themes of poverty, religious self-renunciation, the art historical motif of the beggar, and shame. Her work takes time, since it is conceptually so rich, though her prints are visually arresting in their simplicity, displaying an extraordinary eye for design.

This is the most exciting year for the Turner Prize I’ve witnessed. Having gone in confident that Anderson would blast the other three, I’m now not so sure at all. The best exhibitions, and that includes the Turner Prize, are often ones that surprise you. They make you not only think, but rethink. They alter what you previously thought, or thought you thought. This year that’s particularly true.

This is the most exciting year for the Turner Prize I’ve witnessed. Having gone in confident that Anderson would blast the other three, I’m now not so sure at all. The best exhibitions, and that includes the Turner Prize, are often ones that surprise you. They make you not only think, but rethink. They alter what you previously thought, or thought you thought. This year that’s particularly true.