A fascinating exhibition at the Gagosian explores Picasso's obsession with horny beasts and fighting taurines

This is already John Richardson’s sixth exhibition for the Gagosian Gallery. He’s 93, but I still hope it won’t be his last. As Picasso’s authoritative biographer, and an intimate friend until the artist’s death in 1973, he brings impressive intellectual clout to his curatorial efforts. As for the Gagosian, they’re mega-rich enough to put on museum-standard shows that museums themselves are hard-pushed to put on. The loans are always pretty extraordinary and the results nearly always illuminating.

Concision and focus also work to advantage: as prolific and protean as Picasso was, like most artists he also explored ideas and themes obsessively, which means that a relatively bite-sized exhibition that concentrates on just one will often bring greater clarity than something more unwieldy. What’s more, the echoes and conversations these works have across time can bring wonderful surprises. And it’s an undeniable pleasure to continue to be surprised by an artist as famous and as scrutinised as Picasso.

Picasso: Minotaurs and Matadors is what it says on the tin. The mythological minotaur appears in many of Picasso’s best-known prints and paintings, as does the bull. Throughout his life Picasso was an avid fan of the bullfight, and the earliest painting here, which is tiny, is of picador on horseback in the bullring with three figures behind the ring. Picasso painted it in 1889 aged eight, so its ambiguous sense of space and flattened perspective may not after all come down to modernist experimentation, though Spanish masters also deployed such spatial ambiguity, and even aged eight you might be sure that the absurdly precocious Picasso was emulating them.

But apart from its evident charm, what’s so striking about this painting is its sense of the comic. Picasso had a talent for caricature, an art form he loved as an adult, and you can already see that in this small painting. And although he always said that an artist must relearn how to be a child again in order to be an artist, it seems that the eight-year-old Picasso actually had a very grown-up and sophisticated comic sensibility. This makes you doubt whether he ever had to relearn anything. That playfulness, the playfulness of a serious child hungrily taking in the world around him and remaking it with all the tools of his imagination, nascent skill, and, even at that early date, art history, simply never left him.

And how quickly he mastered the remaking of the world. Almost a life-time later, between December and January 1945/6, he gives what you might even consider a masterclass in 11 stages, that is, in 11 lithographs. Here he depicts the bull viewed from the side, the evolving reduction of its form from horns to tail. From a bulky, brooding, muscular beast whose physicality you can almost smell, we end with a nimble, weightless and flattened creature created by outline alone, its head a tiny circle, its two horns a single curved line.

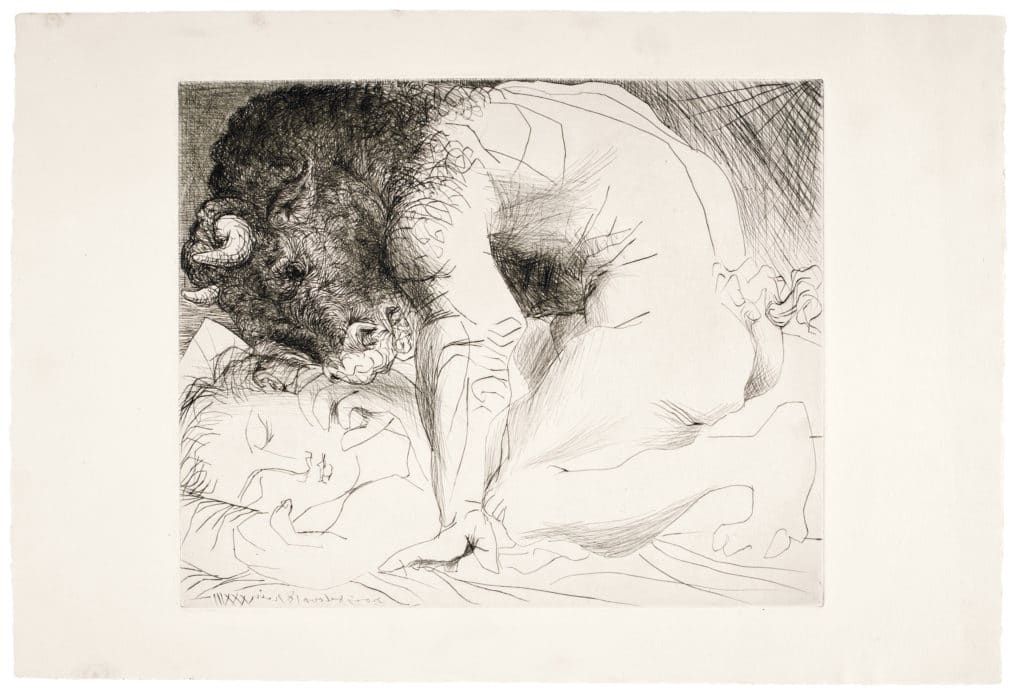

Here too are two etchings from the Vollard Suite, an ambitious series of 100 prints commissioned by and named for Ambroise Vollard, the art dealer who gave the 19-year-old Picasso his first exhibition in Paris in 1901. The whole series was executed during short creative bursts between 1930 and 1937. In the first, Minotaur Caressing a Sleeping Woman, 1934, the hulking form of a minotaur bears down on a sleeping woman whose face resembles Picasso’s young lover Marie Thérèse Walter. This threatening creature also suggests the life-sucking incubus of ancient myth, here preying on the sleeping vulnerability of his mistress. The minotaur is, of course, Picasso’s own sexually predatory altar-ego.

In the second Vollard print, the velvety-textured Blind Minotaur Led by a Little Girl in the Night, 1937, it is now the minotaur and not the mistress who is utterly helpless. With one very long outstretched arm he holds a walking stick and is being gently led by Walter, who in turn is cradling a dove and who now appears in the guise of a child (perhaps, as Richardson suggests, she is also the little sister, seven years Picasso’s junior, who died of diphtheria aged just seven). Raising his head to the starry night sky the minotaur appears to soundlessly howl. In this dream-like and deeply autobiographical work about loss, which is about a loss of potency as much anything else (he had left Walter, who had just given birth to their daughter Maya, two years earlier for Dora Maar) we encounter a precursor to Picasso’s anguished war masterpiece, Guernica, which he began the same year.

Meanwhile, in the tremendous cycle of etchings called La Minotauromachie, 1935, we see an image repeated in different impressions featuring motifs that will later feature in Guernica: the minotaur, the horse, a prone figure who is either dead or has simply collapsed, a lighted candle, a window. But there are other figures, too, including Walter, again as a little girl, who holds the candle and some flowers.

Bulls and minotaurs in dozens of different guises come at you thick and fast. We have hirsute minotaurs, or minotaurs whose hairy heads are almost human. There are ones whose heads are smooth and round and innocent-looking. We have minotaurs that could be goatish satyrs, and ones who look more like ancient gods but for their horns. Of course, there are lots and lots of horny minotaurs.

The range of media includes paintings, prints, sculptures, assemblages, and painted ceramic plates. One plate features a head of a bug-eyed minotaur so striking it’s hard to take your eyes off it. There’s a tiny clay priapic faun that has the same effect, and high on a wall you’ll find the famous bull’s head that’s simply a bicycle seat with upturned handlebars. You’ll also find film footage, including a Pathé news reel of Picasso attending a bullfight accompanied by a media throng. Projected photos include Picasso donning costume minotaur heads.

The exhibition, which occupies only the ground floor of the vast Gagosian Gallery in Mayfair, features around 50 works in all, and it feels rich and dense beyond its size. Instead of white walls, we find walls covered by a green pleated curtain, as if we’ve entered a space where drama awaits us, or even a hushed sacred space. And in a sense we have.