The early years: a focused and illuminating exhibition

An artist as inventive and as protean as Picasso, and one who ceaselessly absorbed influences throughout his life, will inevitably present an ever-changing face to the world. Hence, we have an apparently inexhaustible supply of exhibitions devoted to him.

Two UK exhibitions last year were of particular note: the ambitious but skewed Peace and Freedom at Tate Liverpool, which interpreted the work solely through the single, distorting lens of Picasso’s “political activism”, and the Gagosian Gallery’s Mediterranean Years, which, in simply highlighting Picasso’s playfulness, was by far the more beguiling and seductive.

Gagosian’s exhibition, curated by Picasso’s biographer and friend John Richardson, excelled because it had no overarching artistic agenda through which to narrowly view each work. And it helped that it was beautifully displayed.

This year, there are two exhibitions of note, both of which opened last month and both outside the UK. The first is Picasso: Guitars 1912-14, at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, which features the many collages and groundbreaking assemblages Picasso made of guitars (constructed with cardboard, paper, string and wire, his first guitar “assemblage” challenged what sculpture could be). The second is at the wonderful Van Gogh Museum. Their excellent Picasso in Paris 1900-1907 focuses on the Spanish artist’s formative years. It explores the many and varied avant-garde influences that confronted him as a young artist.

What’s so refreshing about this tightly focused exhibition, which is arranged in four small but distinct sections, is that it allows the work to speak for itself. In so doing, it gives full rein to Picasso’s mercurial, restlessly enquiring mind. And what a precocious mind. At each stage we can see what he took of the techniques he mixed and matched of other artists, and made distinctively his own.

Picasso first arrived in Paris aged just 19. He had been assigned to cover the Exposition Universelle, the city’s major art fair, for the Barcelona journal Cataluaya. This is where this exhibition begins. A hasty and vibrant charcoal sketch by him, Leaving the Exposition Universelle, shows him with a group of high-spirited friends, tottering and swaying drunkenly, posing and performing inelegant high kicks, outside the fair. The writer and fellow Catalan Carles Casagemas is among them, as is the latter’s love interest, posing seductively with her razor-like, femme fatale smile.

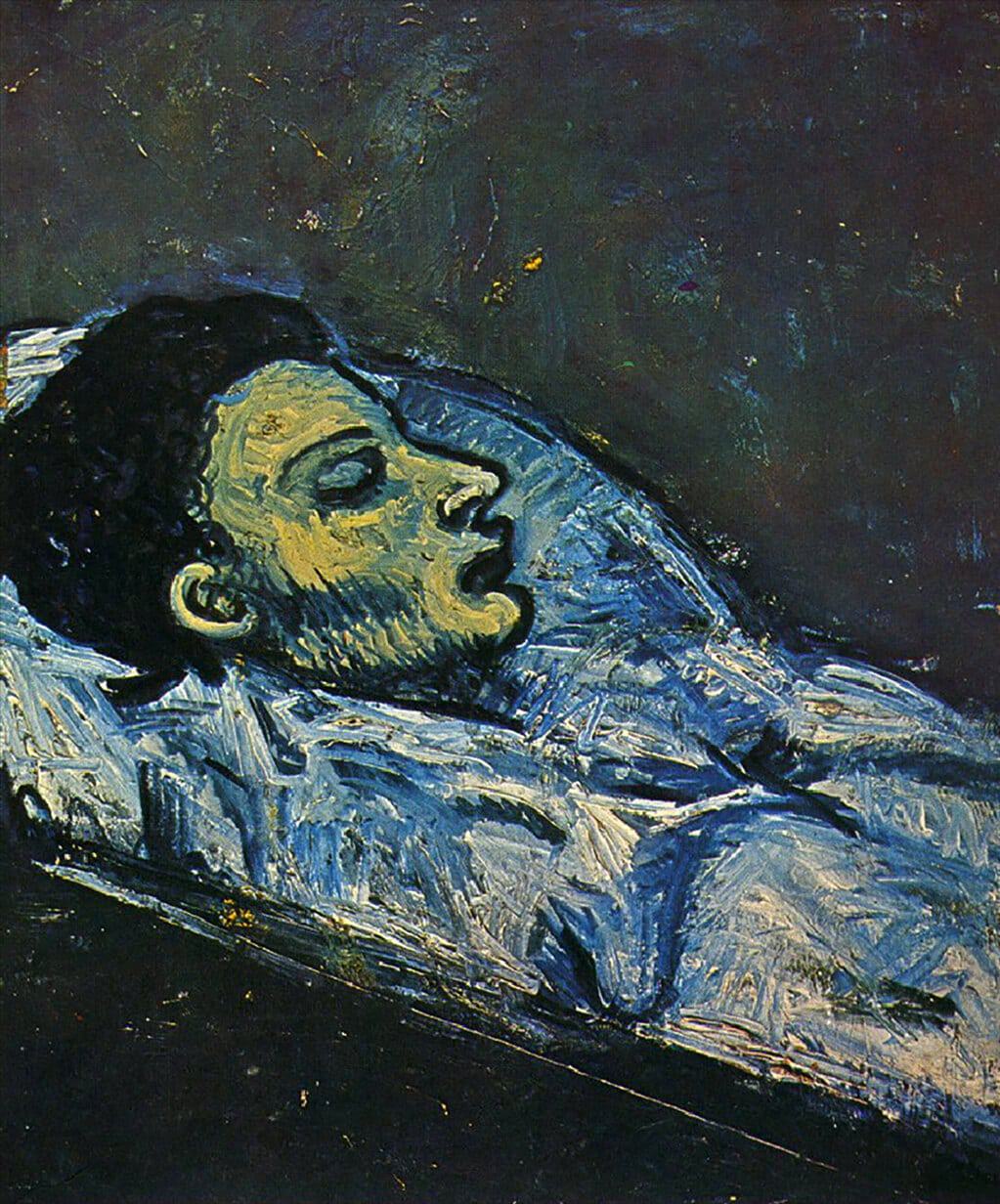

Casagemas’s later suicide over the end of his love affair with the provocatively posing young women, would, understandably, have a huge impact on Picasso – they had travelled to Paris together and were extremely close. It also precipitated his Symbolist Blue Period, with its focus on society‘s most down-trodden members. The death was also a subject that Picasso would return to, painting the head of his friend as he lay swaddled in his coffin, in a series of strange and arresting images, two of which we have here.

But the purpose of Picasso’s initial visit to Paris hadn’t only been to cover the fair as a journalist. His painting Last Moments had been selected to hang in the Spanish section in the Grand Palais. The finished work no longer survives, but a study shows a priest at the bedside of a dying woman. This subdued, melancholy work had been shown five months earlier in a group exhibition in Barcelona. With its pious theme it reveals little of how the exuberant nightlife of Paris – the bars, the brothels, the popular entertainments and the streetlife – would soon capture Picasso’s imagination.

He depicted this heady new life not just with vibrant colour, but with the fragmenting forms of the avant-garde French art he was newly exposed to. And as early as 1900 his colours were extraordinary: vivid and often jarring. The Embrace, 1900, may have been inspired by a painting by Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen, an early influence, but Picasso’s rather acid palette bears little relation to the original.

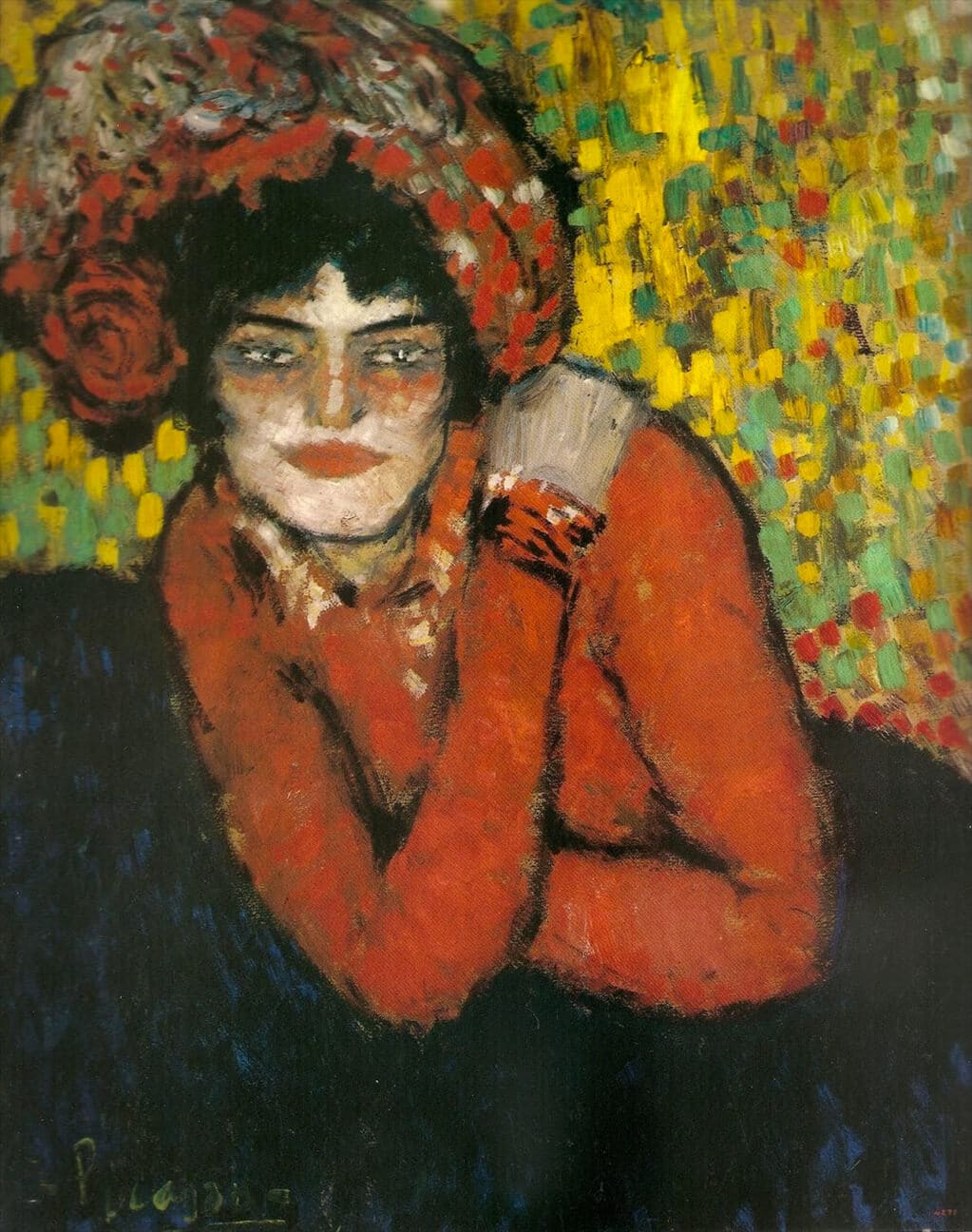

By the time of his semi-permanent move to Paris the following year – where, like many of his fellow artists he eked out an impoverished living in the artists’ quarters of Montmartre and painted on throwaway cardboard instead of expensive canvas – the influence of artists such as Toulouse-Lautrec, as well as the Post-Impressionism of Van Gogh, Cezanne, Gauguin and Seuret is more than evident: can-can girls painted with thin, febrile brushstrokes; the graphic, sinuous lines of the attenuated forms of cabaret singers; the glazed and insouciance stares of prostitutes painted with the dashes and dots of Pointillism.

The cool, ethereal paintings of his Blue Period seems to offer a radical change of mood, but Picasso’s path, is, in fact, anything but linear. A brilliant 1905 painting Portrait of Benedetta Canals takes us back to his Spanish, realist roots, which, in fact, coincides with his so-called Rose Period – or as the exhibition’s curators of this exhibition prefer, his Bohemian Period – with its lithe and melancholy troop of circus performers.

We leave this exhibition on the radical cusp of Cubism, just seven years after Picasso’s first visit to the city. Sketches for the 1907 groundbreaking masterpiece Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (you’ll have to go to New York’s MOMA to see the actually painting) which, with its violent distortion of form and flattened depth of field, introduce us to the beginnings of Cubism, complete this elegantly focused and illuminating survey.