A surprisingly moving encounter with artists in front of the lens

One’s first thought on hearing of Tate Modern’s current photographic survey might be, “Yeah, that sounds a bit worthy and dull.” Like a bad dream in which a false exit just leads through to a descending circle of labyrinthine corridors, I anticipated room after room of grainy photos of 70s happenings – and Bruce Nauman doing his finger exercises in his studio – with little hope of a fast escape.

This just goes to show we should never judge an exhibition by its title, since my first two thoughts on actually seeing it were, “I could spend all day here, and I want to come back.” (Which I did). Incidentally, my first thought on leaving the exhibition was, “Why are these big thematic surveys so much better at Tate Modern than at Tate Britain?” (There are a number of possible reasons, which I won’t dwell on here, including curatorial over-ambition undermined by the comparative paucity – the painful patchiness – of its British collection).

But back to Performing for the Camera and what it is and what it is isn’t. It isn’t just about happenings and performance from the 60s and 70s, though those are the two decades that saw the explosion of performance and grainy black and white stills in which artists ‘explored the body’ – though, somewhat surprisingly, some major figures and works from the highpoint of documented performance are missing. Why no sign of Chris Burden’s actions of self-torture, in which he subjected his body to shootings, nailings and various depredations? And, indeed, where’s Bruce Nauman’s more cerebral and witty pieces – I’m thinking Self-Portrait as a Fountain, a wonderfully layered, punning take on Duchamp’s Fountain?

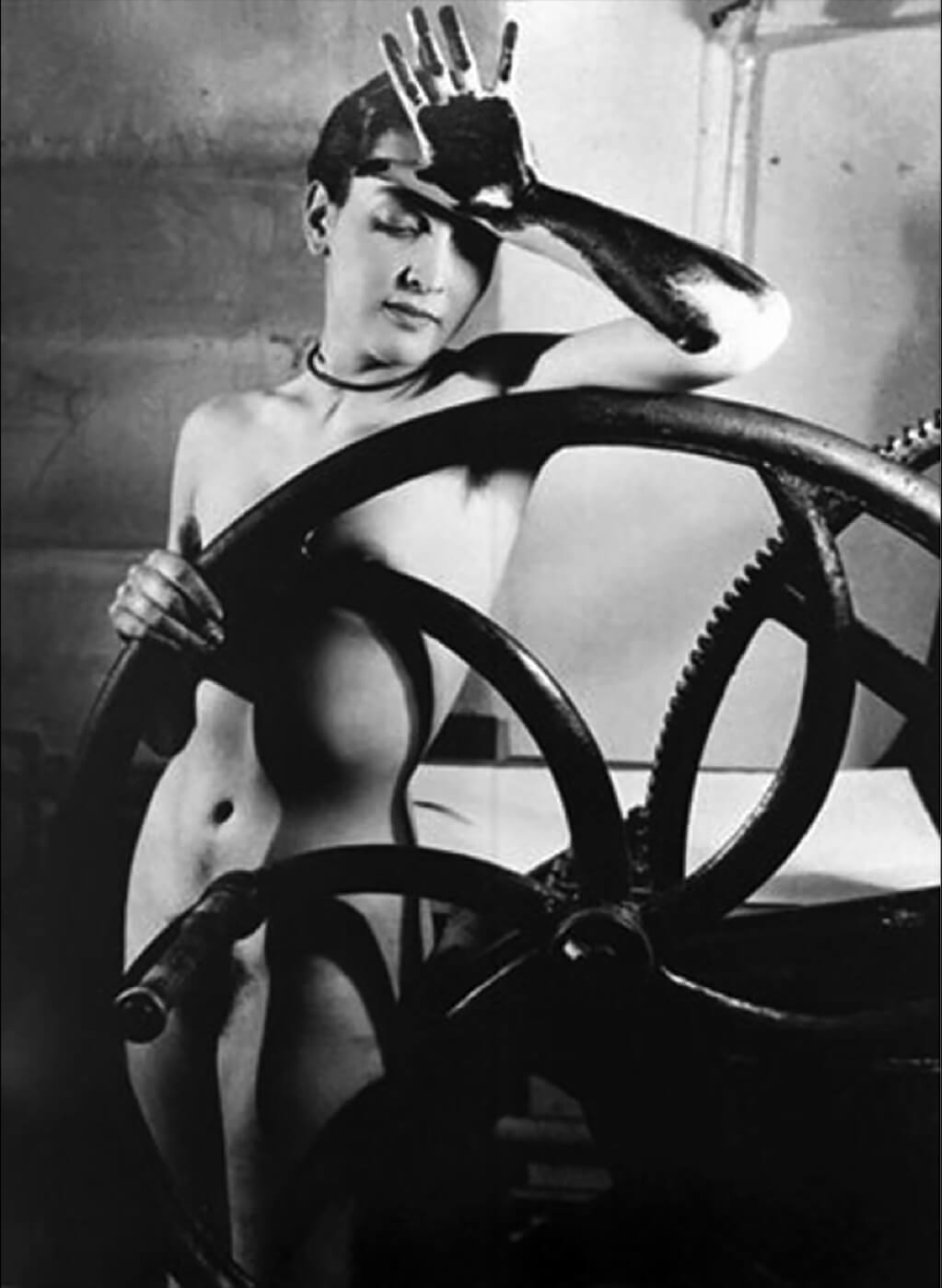

Duchamp himself makes an appearance here, notably photographed by Man Ray (in the guise of the biblical Adam and as female alter-ego Rrose Sélavy). Man Ray provides some of the most arresting images here, including his wonderful surreal portrait of Surrealist Méret Oppenheim (she of the suggestive furry cup – the innocently named Object of 1936) posing with a printing-press wheel whose generously proportioned handle stands in for an erect penis. So the concept of performing for the camera, with its focus on the body and identity as a tool for art, is here necessarily a rich and expansive one, though thankfully not exhaustive. In fact, the exhibition brings together over 500 images spanning 150 years, and, what’s more, excludes video. If it didn’t it might well require three separate trips.

So, this is a huge exhibition which must have greatly exercised the editing skills of the curators (Tate’s photography curator Simon Baker and assistant curator Fiontán Moran). As well as works covering the whole of the last century, we have works from the 19th. The earliest is a ‘performance’ self-portrait by photography pioneer Hippolyte Bayard, bitter rival to Louis Daguerre.

Bayard invented a process called ‘direct positive printing’, but was robbed of his legacy when a friend of Daguerre persuaded him to postpone revealing his technique to the French Academy of Sciences. This Bayard only did in 1840 – too late, it seems, to capitalise on his invention. His Self-Portrait as a Drowned Man, taken that year and using the technique he had developed, is a reaction to this injustice: slumped and stripped to the waist, he plays the part of a man who has resorted to suicide owing to the neglect of his great invention. A ‘suicide note’ written on the back of the image gives his reasons, though in fact Bayard didn’t die until 1887, well into his eighties, and he’d lived long enough to see photography develop as a medium for exploring guises and disguises.

Indeed, among other such early images is one controversial work by American photographer F. Holland Day. Emaciated (he starved himself for the role) and wearing a crown of thorns, Day poses as Christ on the cross in an 1898 work titled The Seven Words. Beneath, in captioned titles for each of the seven images, are the last words of Christ. When modernism emerged, Day’s pictorial style went out of fashion, but his inclusion in museum displays such as this one is certainly making many more curators take an interest.

Meanwhile, among the usual but highly welcome suspects are Claude Cahun (playing with gender), Yves Klein (leaping into the void; deploying live women as ‘paintbrushes’), Cindy Sherman (faux film stills), Robert Mapplethorpe (bad boy in leather jacket wielding a knife), Joseph Beuys, Andy Warhol, Jeff Koons (all three depicting themselves as if on movie and magazine posters in a section called Public Relations), Francesca Woodman (disappearing into the fabric of her surroundings), Lynda Benglis (armed with plenty of attitude and a gigantic swinging dildo), and Hannah Wilke (a goddess-messiah in sexy slingbacks).

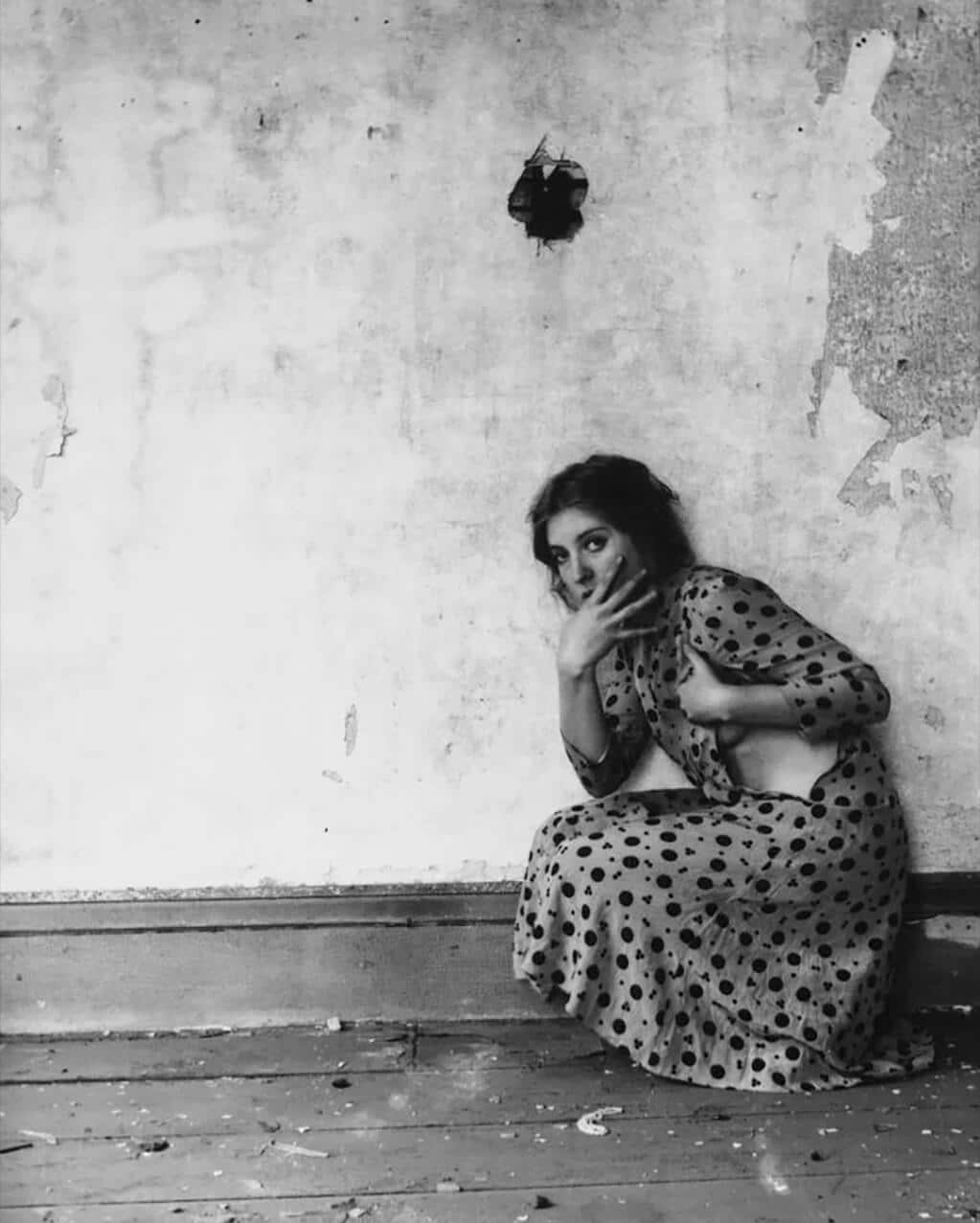

But it’s also great that we’re introduced to artists who are not so well-known. I was particularly moved – and this is an exhibition surprisingly full of visceral moments – by Masahisa Fukase’s sequence of photographs (1991). Taken over the course of a year in the aftermath of a divorce, we see his head submerged in water in his bath tub, or bobbing above its surface, perhaps refracted or fractured (drowning once again a theme). What we feel is a man utterly stripped, vulnerable, raw. A man who suddenly feels his age. Goddamit, he looks in such pain.

There are in fact many arresting, and intensely emotionally engaging moments – sad, tender, funny, funny-sad – throughout this vast and superb survey.