The enigmatic, conceptually driven works of an American neo-dadaist

Jasper Johns’ name will be forever linked to Robert Rauschenberg’s. They were partners in art and life during the time they made their most exciting work. They exchanged ideas fuelled by their discovery of Duchamp, and they were introduced to those ideas by another avant-garde couple, the composer John Cage and choreographer and dancer Merce Cunningham. These friendships led to many fruitful collaborations.

But in the Royal Academy’s vast exhibition you get almost no sense of these relationships, certainly not as you did at the excellent Rauschenberg retrospective at Tate Modern last year, and which was very much one of that exhibition’s strengths. This is a retrospective spanning six decades and with some 150 paintings and sculptures. But it still manages to exclude some key works, and not just the collaborations but some of Johns’ paintings, those mysterious Target paintings, for instance, that include compartmentalised casts of his own body parts and that of others.

Somehow the exhibition still manages to feel overstuffed. One understands the difficulty of securing loans – and the curators have managed some terrific loans, particularly from the Philadelphia Museum of Art – but despite this, it could still have done with some judicious editing.

Johns and Rauschenberg had met in 1954, the same year that Johns had his well-documented dream about painting the American flag. At the same time he wanted to work on things ‘the mind already knows’, which meant making art using familiar objects. In this way, the viewer’s perceptions might be teased, since the process of making art about familiar things would render them unfamiliar and strange, in exactly the same way that Duchamp’s readymades were rendered unfamiliar and strange by being decontextualised. The object could then be perceived as an abstract form, in addition to everything we might know about it and the associations it might throw up.

As first, Johns tried painting the flag with enamel paint, but found it dried too slowly for him to layer on the paint quickly enough. So he tried encaustic, an ancient method of mixing pigment with hot wax, which hardens and dries almost instantaneously, leaving a textured surface. His first American flag used encaustic with collaged newspaper, and underneath the bumpy and textured surface and the flurry of brush marks, you can faintly detect newsprint.

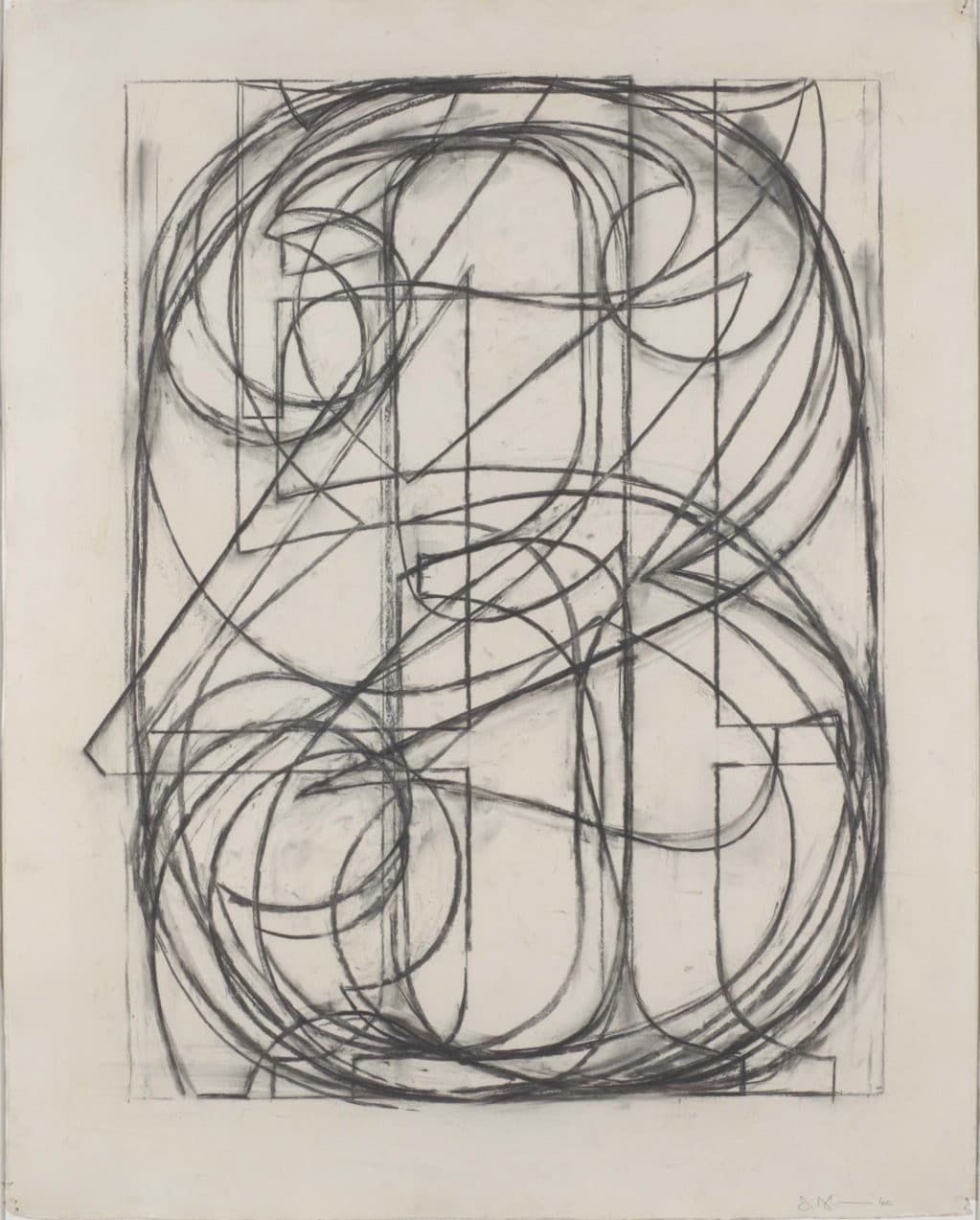

The question that was asked at the time was, Is this a flag, or a painting of a flag? The same might be asked of his target paintings, though one can certainly be less equivocal about his number motifs. A number is a number, even if it’s a painterly painting of a number, and even if you layer the numbers to deliberately obscure each one. This Johns often did in the most gorgeously painterly way, or as he does in his beautifully rendered drawing 0 through 9 (1960). Yet when you’re looking at a tangle of lines, some more faint than others, the image keeps shifting, so that you might discern the number 3 one moment, and then the zero. He is teasing our perceptions.

Like so many of his everyday motifs, Johns painted The Stars and Stripes again and again, in different media and sometimes choosing to recreate it in sculptural form, as in the three layered canvases of Three Flags. Neither his original flag, nor the 1958 Three Flags are in this exhibition, but it’s not really the specificity of each flag that matters (unless you’re a collector, or a museum) for Johns immediate concern is to do with signs and motifs and how our perceptions shift when reading them as they’re rendered in slightly unfamiliar ways.

Still, the artist who broke the dominance of abstract expressionism often deployed, just as Rauschenberg did, an expressive painterliness as a way of ‘quoting’ the dominant New York movement of that time. This referencing, as well as a focus on found objects and appropriated images, began the shift from modernism to postmodernism, a move that also saw neo-Dada eventually turn into consumer-obsessed Pop art and text-based conceptualism.

Johns is a far more conceptually driven and reflective artist than Rauschenberg ever was, though what Johns lacks and Rauschenberg possessed is an arresting visual eloquence. This becomes increasingly evident in this survey. Johns is a great draughtsman and a brilliant printmaker, but when he moves away from his readymade signs – the flags, the targets – to his own large-scale compositions, there can be a flatness and stiffness. And in a way, he’s simply not as radical an artist. He didn’t make art out of anything he could get his hands on in the way that Rauschenberg could, such as a series of cardboard boxes splayed out as an elegant and minimal relief. And there’s a different, darker mood at play.

It’s not a flatness, but a sombreness. Death rears its head several times, and there are intimations of drowning, of suffocation. An imprint of a hand reaches from the centre to the edges of a void-like circle in the 1963 painting Periscope (Hart Crane), named for the American poet who jumped off a steamship and drowned in the Gulf of Mexico aged just thirty-two. The last thing that was seen of the poet was an outstretched hand.

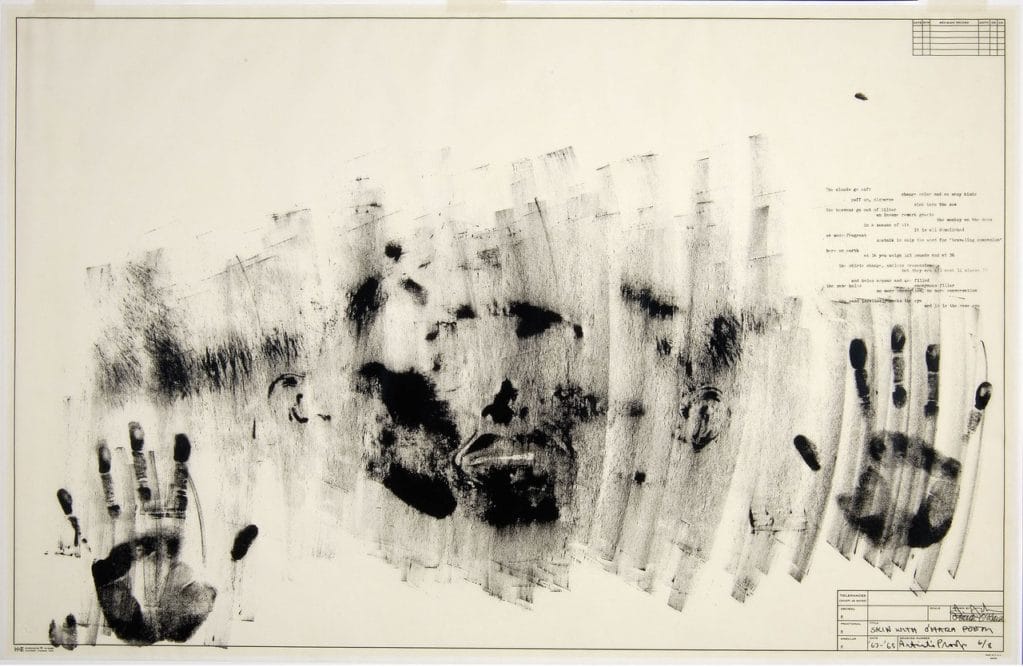

Hands keep cropping up, including in the ghostly smeared imprints of the artist’s hands and face of the faintly disturbing Skin with O’Hara Poem, 1964–65. This is one of a series of works in which Johns had applied baby oil to his head and hands and pressed them onto a sheet of paper to leave an invisible imprint. Charcoal applied with the repetitious and mechanical motions of his arm revealed the image. We glimpse a figure trapped for eternity in his own artwork. And in one corner there’s the text of a Frank O’Hara poem: “The clouds go soft / change colour and so many kinds / puff up, disperse / sink into the sea.”

One of his most recent bodies of work is the wonderful and beguiling Regrets. Fifteen small prints from the series are arranged grid-like on one wall. Johns began the series in 2011, the year his friend Cy Twombly died, and the prints depict a skull, which actually resembles the shape of Johns’ own elderly jowly face, resting on something that looks like a tombstone. But the image emerged completely fortuitously.

What the drawing actually is is a picture of Lucian Freud, sitting on a bed and with his head in his hands. The source of the image is a battered photograph of Freud taken in the fifties by John Deakin for Francis Bacon, so that Bacon could use the image as his own painting source. Johns spotted the photo in a Christie’s catalogue, hardly knowing where it would lead him. Only when he doubled his drawing like a Rorschach, with the right hand image mirroring the left, was the skull and tombstone revealed amid the mosaic of shapes. With a kind of morbid wit, on each of the prints Johns has rubberstamped his signature sign-off, ‘Regrets, Jasper Johns’. Away from his work, and more prosaically, he uses the stamp instead of a handwritten note to decline invitations. The exhibition of this most enigmatic of artists ends on this elegiac high note.