From debauched scenes with Bacon and Freud to the gritty earth of the Thames Estuary, the paintings of Michael Andrews have a creeping sense of the uncanny

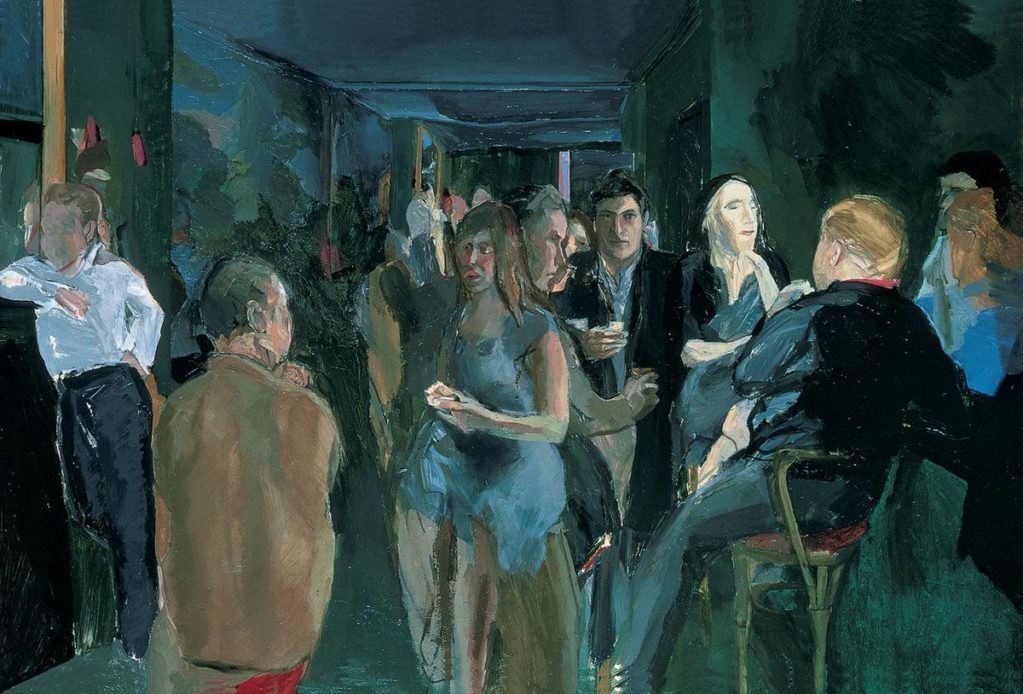

Henrietta Moraes, muse to Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, sits squarely in the centre of the picture. She’s chatting to John Deakin, aggressive drunk and gifted photographer whose most famous image is of a bare-chested Bacon with two carcass ‘wings’. All we can see of Deakin is his back, and amid the tight cluster of bodies there’s a wide chasm between him and Moreas. The distance is telling, since she later described him as a ‘horrible little man’, recalling his insistence she pose naked for him in bed with her legs wide apart (photos that were the basis of Bacon’s contorted paintings of her).

Meanwhile, Bacon, a semi-permanent fixture in the place, props up the bar with proprietor, landlady, Bacon model and ‘queen of Soho’, Muriel Belcher. Diametrically opposite, and echoing Bacon’s slouching posture, is Jeffrey Bernard, who is alone. Bernard’s profile is reflected in the mirror directly behind him, his whole head a shadowy smudge, suggesting his state of inebriation. The only figure in the room who looks at us directly, or rather at the artist, is Freud. An intensely alert and brooding presence, Freud cuts through the fuggy atmosphere with his familiar piercing gaze.

This 1962 painting, The Colony Room I by Michael Andrews, is a dour postwar equivalent of a 19th century atelier painting featuring a gathering of esteemed artist colleagues. It depicts the artist’s friends – Andrews was associated with the so-called London Group which also included Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff – at the Soho members club that was the epicentre of bohemian life for a small clique of artists and writers.

Andrews died in 1995, aged sixty-six, and was a notoriously slow painter, leaving behind only around 250 paintings. And so, from a relatively small output that spanned forty years, The Colony Room is probably Andrews’ best known work. Here it features at the start of a survey largely devoted to his last twenty-five years: the two decades that saw Andrews turn away from the figure and focus on landscape and nature. It’s also a period that, unlike the work of most of his contemporaries with their impastoed peaks and slabs, saw him move away from expressive brushwork. Dispensing with the brush and palette knife, Andrews worked instead with a spray gun filled with acrylic paint that stained the canvas rather than built up layers of oil, occasionally adding patches of sand and gritty earth to, for instance, his large Thames Estuary paintings (two of which are included here).

With this new method of working, Andrews concentrated on works in series, including his cycle of Light paintings (featuring the mysterious, often improbable travels of a hot-air balloon), his strikingly bold Australian Ayres Rock paintings, his exquisite paintings of shoals of fish, his Scottish deer-stalker paintings and his English landscapes.

We also find smaller studies for his arrestingly weird Parties cycle from the sixties (The Colony Room I is an early work kicking off the series), where, collage-like, disparate and fragmented figures, often strangely withered-looking like deflated balloons, feature in interior settings that are themselves oddly fragmented and compressed. Juxtaposing isolated moments of violence and hilarity, sexual abandon and existential isolation, these works possess a mind-warping, hallucinatory quality, both disorientating and disconcerting. They also show that Pop art didn’t entirely pass him by, as it did Freud, Bacon, Auerbach, and Kossoff.

Michael Andrews, Thames Painting: The Estuary (Mouth of the Thames), 1994-95, courtesy Pallant House

Some of the most arresting works in this exhibition are small studies for ambitious commissions that are not themselves included here, such as the two portrait heads that were studies for his masterly and, again, utterly strange 1966-9 painting The Lord Mayor’s Reception in Norwich Castle Keep on the eve of the installation of the first Chancellor of the University of East Anglia, to give its full title. In a sense the painting’s title is misleading, for this is no ordinary depiction of pomp and ceremony: there’s little sense of the figures in the finished work either relating to each other or to the space around them. They appear rather like trapped specimens under glass, particularly the two figures pressed against the picture plane at the bottom of the canvas. Blindly staring out at the viewer, they appear to break the fourth wall of this uneasy theatrical tableau. As for the studies themselves, there’s something achingly tender about these oddly frozen faces that suggest faded newspaper cut-outs, uprooted from any context.

What really stands out about Andrews, above any of his peers, in fact, is what an unusual eye he had, so that even his most seemingly conventional and conservative landscapes have a creeping sense of the uncanny. Their strange angles and improbable perspectives often suggest the scene is being viewed by some spectral being unconstrained by the normal rules of physics. We see this particularly in his hot-air balloon paintings, which are inspired by the Zen Buddhist philosophy he was reading at the time. And most starkly in Cabin (1975), which depicts the front end of a passenger jet impossibly observed from above.

One guesses that the later paintings, of deer-hunting and old-fashioned English country scenes, must have marginalised him somewhat in the art world, especially in relation to his high-profile contemporaries. On the face of it, they appear rather too concerned with the leisured pursuits of the upper middle-class, as opposed to the rough and shadier sides of life that still excited his Colony Room pals. But in fact they retain enough of an oddness to still captivate. And technically he was simply a tremendous painter, far more talented in this regard than Bacon.

Under the radar for too long, and with so many paintings in private collections, little has been seen of Andrews since his posthumous Tate Britain retrospective in 2001, so this is an inestimably welcome survey.