An extraordinary new exhibition at The Hague's Gemeentemuseum follows the arc of the abstract expressionist's career from beginning to end

Mark Rothko was an abstract artist who didn’t see himself as an abstract artist — or at least not in any ‘formalist’ sense. If a critic called him a ‘colourist’, he would bristle; if they admired his sense of composition, he would complain that this was not what he was about at all. His was an art of deep content, his subject an invocation of the religious, the tragic, the mythic. “The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them,” he once said. “And if you, as you say, are moved only by their colour relationships, then you miss the point.”

But you don’t have to go all the way to the Rothko Chapel in Houston, which houses the artist’s 14 monumental black paintings, to get the sense of a religious encounter. At The Hague’s Gemeentemuseum an extraordinary one-off exhibition follows the arc of his late-blooming career through to its end, the end being not a brooding black painting but one final burst of rich colour — a bright red canvas that follows a long parade of increasingly sombre paintings. It was painted just before his suicide, aged 66, its colour noted as a signal of his intentions — his body was found shortly after in a pool of blood. He’d cut his wrists in his New York studio.

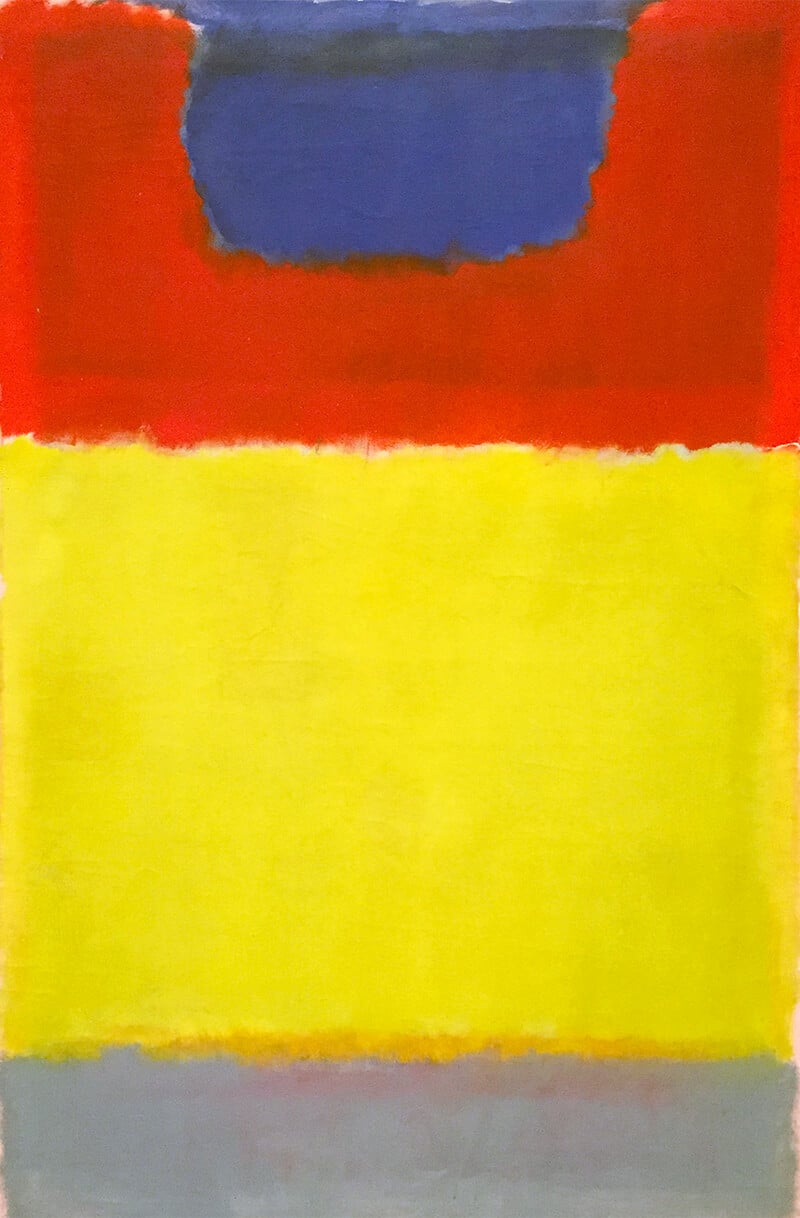

At the Gemeentemuseum, Rothko’s strict stipulations about the lighting and the low hang have also been observed, but in these 40 or so paintings, all on loan from the National Gallery of Art, Washington, you also get a chance to observe how Marcus Rothkowitz becomes Rothko, the mythic superman of mystical abstraction. He was already in his late thirties by the time he officially changed his name to that slightly anglicised one; and by the time his “classic style” finally emerges in the 1950s, the period of his floating horizontal bars shimmering against shimmery backdrops, he’s already in his late forties.

Viewing the early paintings (which are seen very rarely in one-off displays), one gets a proper sense of the blood-and-sweat struggle to get there. His early figurative paintings are often awkward, with a naïf sweetness that is almost cloying. His human figures are doll-like. They stare past you with blank, beady eyes. This is the American Ashcan School mixed with surrealism-lite and with the merest hint of German expressionism — but denuded of its punch or passion, or indeed purpose.

Just one example of his New York subway series is here: Underground Fantasy, c.1940 (pictured), which features six elongated figures standing on a platform, looking a bit like ancient Egyptian figures in 1940s dress. Hints of pink and yellow relieve the brown and magnolia drabness. Rothko has not yet found his feet as a ‘colourist’, but the soft palette and blurred edges of his later abstractions are already in place.

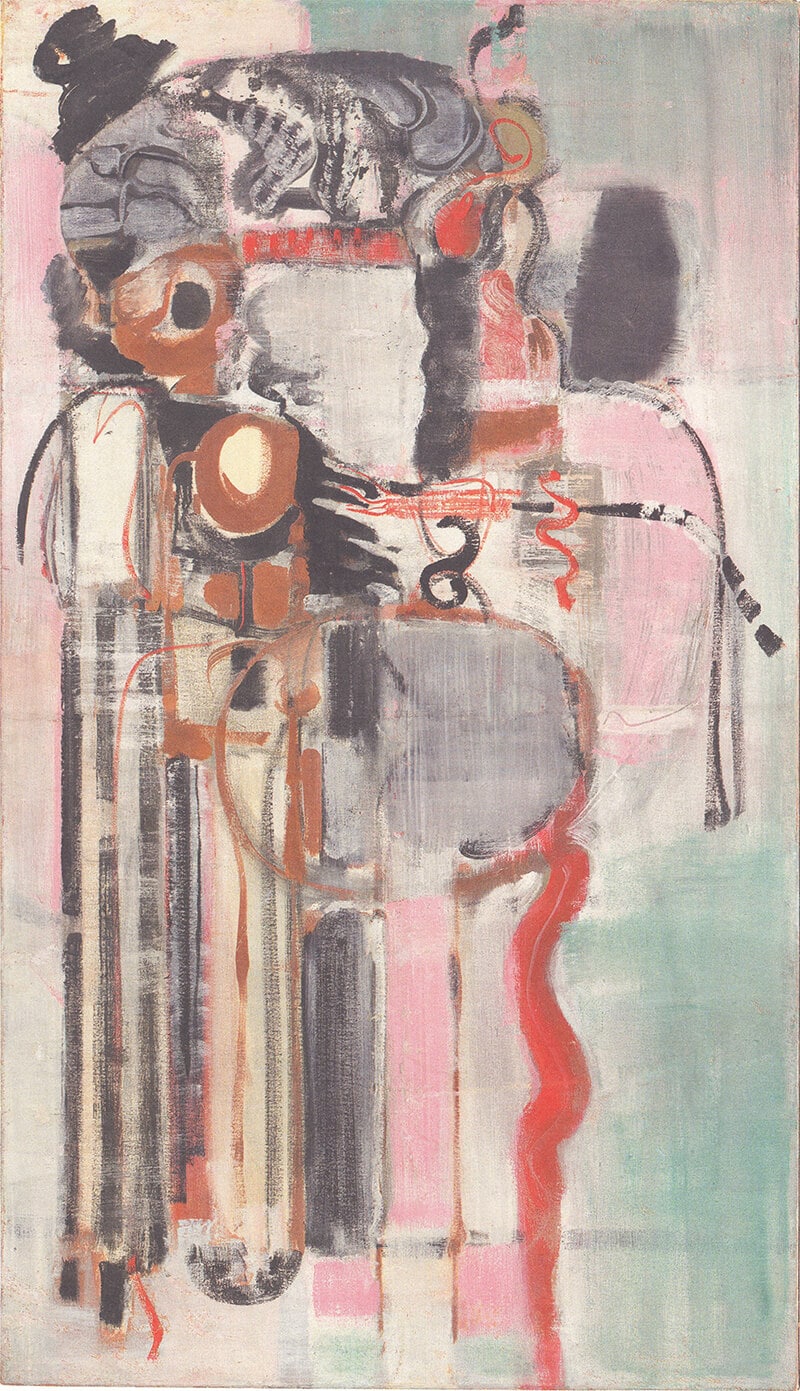

Absorbing literary themes from Greek mythology to Nietzsche, Freud and Jung, Rothko moves into fully fledged surrealism. But this period of work doesn’t entirely convince either. It feels mechanical, a little studied, a bit too academic. It’s as if he doesn’t feel entirely at ease with his forays into the subconscious. He is like a cautious man, dipping a toe before taking the plunge, only to find himself bobbing along in shallow waters but still clutching a life-raft. Unlike the intuitive Pollock, Rothko is a bookish intellectual and perhaps overthinking is one of the obstacles he has yet to overcome.

By the mid-1940s another shift occurs – a breakthrough – and we have the softly layered ‘multiforms’. These finally begin to pulsate with a life of their own. The early multiforms, with their frothy, seductive colours and tentative, amorphous shapes are all ‘Untitled’, while the later ones are simply numbered (one zingy vertical canvas, whose horizontal bars and stripes sing out in buzzy acid greens, yellows and reds, is either No. 7 or No. 11, according to the catalogue and label). And as you proceed the canvases get bigger until the paintings eventually tower over you.

In one gallery he is paired with Mondrian, of which the Gemeentemuseum has the world’s largest collection. He and Rothko never met, though the celebrated Dutchman, by then the most collectible abstract artist in the world, had moved to New York in 1940. But Rothko was almost certainly influenced by him, taking something of Mondrian’s cool precision and horizontal and vertical structuring. ‘Blurry Mondrians’ was how some critics described his paintings. On a kind of memorial wall, the unfinished Victory Boogie-Woogie (Mondrian’s last work) hangs next to Rothko’s last painting, stained with that surprising blush of red. Despite its colour, it’s actually a rather austere, solemn painting – much smaller than any of his other late paintings – while Boogie-Woogie’s syncopated rhythms are the opposite.

A selection of huge Seagram murals – in a blaze of dark reds, maroons and inky blues – offers a fitting finale. They grab you by the neck and stun you with a velvet cosh. This revelatory show isn’t travelling, so expect it to be the most comprehensive exhibition you’ll see of the artist in Europe for some time.