A desiccated foray into a movement whose radicalism gave way to a strangling orthodoxy.

Art as negation. Art as a text. Art as indexing. Art as system. By the time you’re done with Conceptual Art in Britain 1964-1979, Tate Britain’s desiccated foray into a movement that rejected the precepts of the past – throwing out the visual, dispensing with the object, and concerning itself only with the self-reflexive idea – and quickly became the ossified orthodoxy, you’ll wonder just how an art movement so puritanically joyless, so relentlessly obtuse to the point of self-parody, could become the officially sanctioned lingua franca of the art world.

This is an arid survey of a movement that was certainly prone to aridity, but which could also be genuinely exciting, provocative, funny and self-aware. But there’s not much evidence of these attributes in this bleak survey. Keith Arnatt “eating his words” in a series of photographs where he appears as if he’s about to wolf down scrunched up sheets of paper (literally consuming and regurgitating words is something of a theme in conceptual art – see also John Latham) and Bruce Mclean’s familiar Pose Work for Plinths, in which he contorts his body over three plinths of differing sizes in a whimsical parody of the monumental figures of Henry Moore (with an accompanying dig at minimalism’s grids and boxes) are two works that inject levity and humour. Both are otherwise in short supply. But it’s not as if one is longing for a laugh a minute. Just some human connection will do. Instead we’re left circling and flaying amid screeds of documentation, in search of a beating pulse.

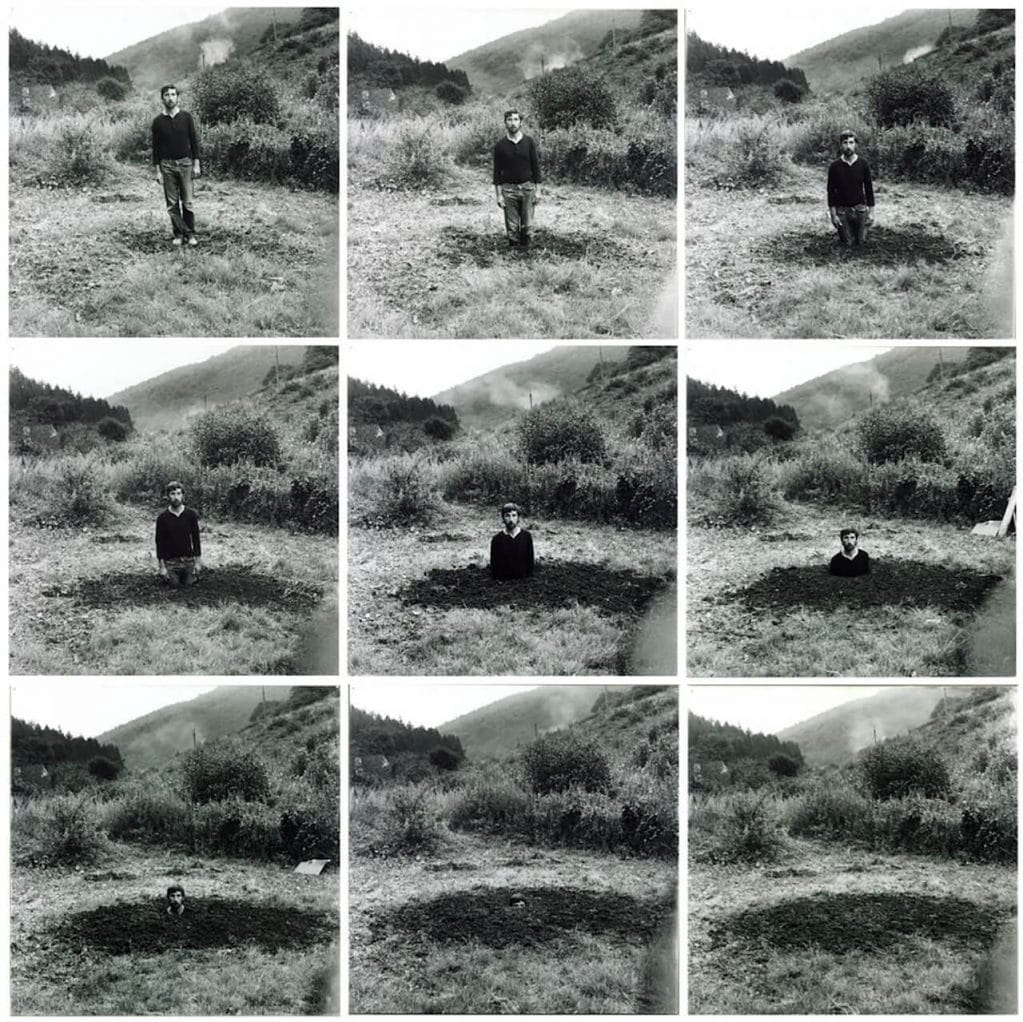

That said, one of the better pieces in the exhibition is Arnatt’s Self-Burial (above), in which nine photographs of the blank-faced artist show him standing on a mound of fresh earth at different stages of his burial. He cuts a quietly absurd figure, like one of Beckett’s hapless characters. The last photograph simply shows the mound of earth: going, going, gone.

What must have given this work its disruptive potency is the manner of its debut as a television ‘intervention’. In 1969, unannounced and with no commentary, Arnatt’s images were broadcast on German television, displayed for a few seconds, and then repeated the following evening, as prime time viewing. Cryptic, jarring, delightfully comic and poetically poignant. If that piece were shown today audiences – at least perhaps British ones – would wonder what was being sold to them. Some kooky hipster clothing range, no doubt.

So why is this exhibition so downright tedious? Well, conceptualism is kind of tough, you might say. It’s hard work and you’ve got to tough it out. Much of the time it’s an endurance test. Rise to the challenge. That’s one argument at least. But is that the only problem here? Or is it perhaps that British conceptualism was always a little weak compared to its American counterpart? Well, I’m not sure I can think of one really great British conceptualist with the intellectual chops to compare to, say, Sol LeWitt or Joseph Kosuth (both pop up briefly here, in fact), though I don’t speak as an unqualified fan of either.

But that’s not really it either, or not wholly it. The real problem is simply a curatorial one.

Why is there an inordinate amount of room given to Art and Language? It’s hard to fathom. The group, who in their heyday published their own journal called Art-Language, were influential, of course. Their historical importance is not in doubt. But they weren’t the only gig in town, even if they did have more interchangeable members than The Fall, and possibly just as many fist-fights and fallings out. Those vitrines filled with critical theory handouts, screeds and screeds of it, all looking badly Xeroxed and occasionally accompanied by a smudgy grey-scale image, proudly bear the studied aesthetic of impenetrability. Who would, or could, read this stuff? This is a world of such self-referential insularity that just being in the same room makes me feel like I’m being buried alive. I think I know how Arnatt felt.

What the curator, Andrew Wilson, has done, is narrowed the arena in which conceptual art played out, so that it’s been artificially shorn of video and performance, which are both perfectly natural overlaps. Even Gilbert and George find themselves stuffed in a vitrine, their Living Sculpture reduced to a few bits of ‘documentation’. What really is the point of that?

And everywhere else, too, the sanitisation of the unruly has taken place. Mary Kelly’s Post-Partum Document, in which she coolly observed her relationship with her son, from his birth to aged six, isn’t accompanied by those grubby nappies that caused uproar when the work was first shown at the ICA in the mid-70s, and we only get a fraction of the piece. You might conclude that Roelof Louw’s Soul City, the depleting pyramid of fresh oranges that visitors encounter when they first enter the exhibition, plays a kind of deception. This is an exhibition largely in monochrome, literally and metaphorically, and if it possesses any soul, it sure feels shrivelled up.