A Spanish master and underrated 20th-century giants of art.

It was a year dominated by paint, glorious paint – and wonderful female painters too, including a revelatory retrospective at Tate Modern of minimalist doyenne Agnes Martin.

It was the year, too, that 20th-century greats generally outdid the Old Masters: Richard Diebenkorn and Joseph Cornell at the Royal Academy, Peter Lanyon at the Courtauld, and the little-known but utterly fantastic minimalist-turned figurative painter Jo Baer at Camden Arts Centre. We also had the peerless Marlene Dumas at Tate Modern (OK, there were some kitschily bad paintings in the Dumas survey, but mostly it was great).

Still, having said that, if you’re looking for one single art highlight of the year, then it must be Goya. The Courtauld’s Witches and Old Women Album bought together a sketchbook of drawings for the first time since the artist’s death, and you can still see the Spanish artist’s knockout portraits at the National Gallery. As we see, Goya was much more than a court painter, but my, what a court painter he was.

As for contemporary art, well, as always, there was the Turner Prize, which this year went up to Glasgow (but, surprise, no Glasgow School of Art alumni). It was, as you might say, an uninspiring shortlist. It appears that in 2015 they couldn’t find an actual artist to give it to (art categories being so beginning of the last century – we really must catch up). Instead the gong went to architecture collective Assemble, and the £25,000 prize money had to be shared among its 18 members. Oh yes, and there was lots of fuss about Ai Weiwei’s Royal Academy survey, which, in the end, was good in parts, but not that good.

There was little that was actually mind-blowingly bad as such, but you can usually rely on some overambitious, anxious curating to piddle on something promising. The Whitechapel Gallery’s Adventures of the Black Square: Abstract art and Society 1915-2015, opened the year and featured some fantastic paintings – a Malevich (it was a black rectangle, mind, not a square), a couple of great Mondrians and a corner occupied by some Russian constructivists. But it was so elastically pulled this way and that it collapsed into an amorphous mess. What makes curators do this?

This year also saw a game of musical chairs among prominent museum directors. Out went Tate Britain’s Penelope Curtis, the National Gallery’s Nicholas Penny, and the National Portrait Gallery’s Sandy Nairne, while the British Museum’s Neil MacGregor is stepping down next spring to take up the inaugural directorship of Berlin’s new Humboldt Forum. MacGregor will no doubt be remembered as one of the British Museum’s truly outstanding directors, and he’s bought us some very memorable exhibitions – last year’s Germany exhibition, for one, which came with its own superb podcast series, and the outgoing year’s Defining Beauty and Celts.

So here are my art highs and lows: five major exhibitions that were memorably great, one that was positively dreary, and two to get you excited for next year. Did I forget anything?

Goya: The Portraits, National Gallery

Crackling with energy and life, sensual and humane, Goya’s portrait paintings appear like snapshots, depicting characters who might at just that moment have been interrupted by either the artist, or by us, walking into the room. What are they thinking? What are they about to say? Until 10 January.

Peter Lanyon, Courtauld Gallery

An underrated British painter associated with the St Ives school, Peter Lanyon’s gliding paintings from the late Fifties to his death in 1964 (from injuries sustained in a gliding accident), reached, well, giddy new heights. One senses that the tantalising freedom of the skies completely liberated him as an artist as he sought to capture in paint the vivid and bracing sensations of soaring above beach and cliff. The Courtauld’s tightly focused exhibition, which continues until 17 January, is unbeatably seductive and gloriously exhilarating.

Jo Baer, Camden Arts Centre

Still apparently going strong at 86, American painter Jo Baer was a hardcore minimalist until she embraced figuration in the mid-Seventies. Her canvases, which reflect an engagement with myth and symbolism, are fluid but restrained, her paint handling deft rather than carefree, yet with fleeting flourishes that bring it to life and capture a very earthy sense of humour. Hers are also paintings full of mystery. Her Camden exhibition, exploring myths and stories from the Giant’s Causeway (she lived in Ireland for a time), was, in its quietly beguiling way, a surprising highlight of the summer.

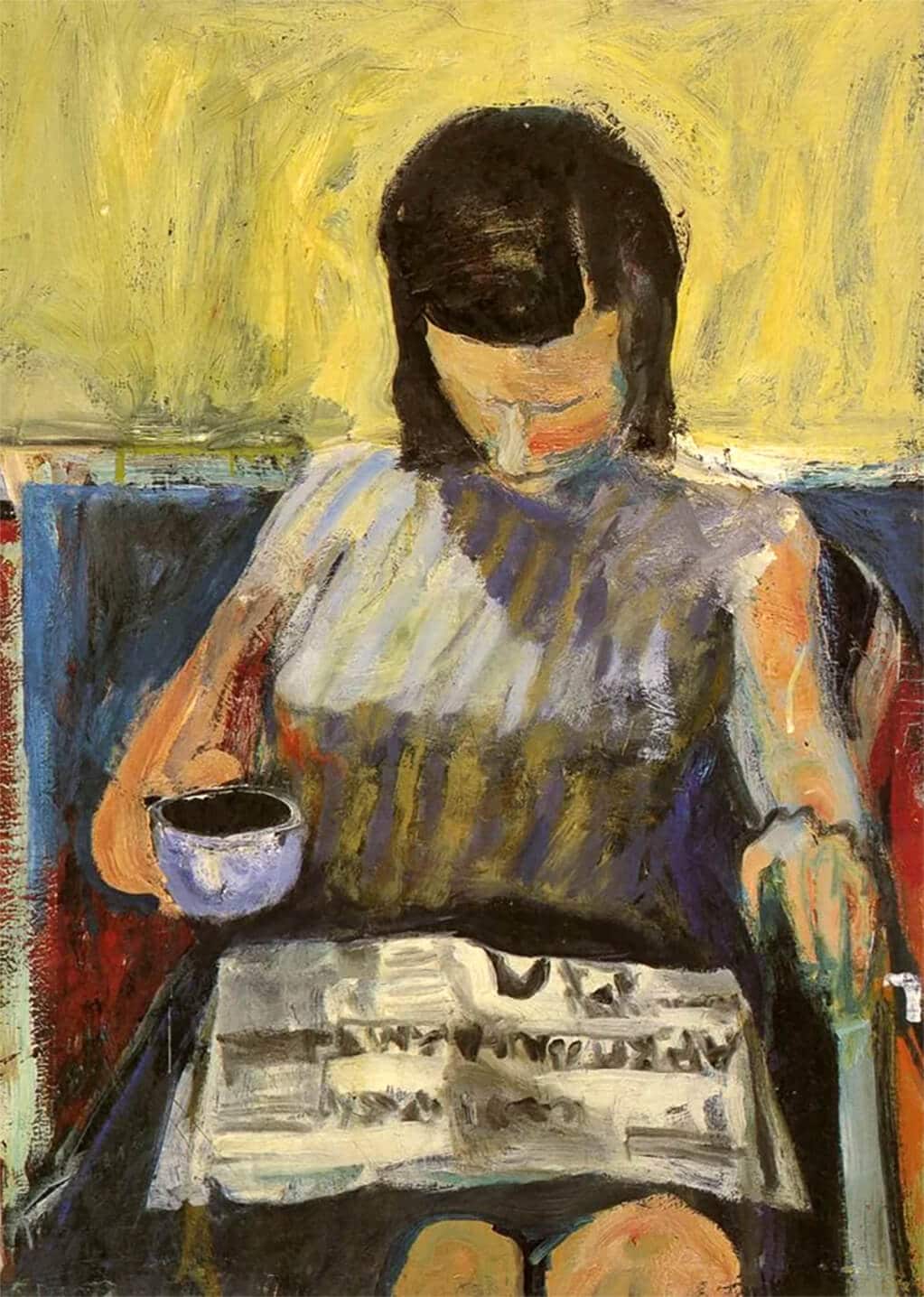

Richard Diebenkorn, Royal Academy

This West Coast painter was a contemporary of the abstract expressionists, but was doing his own thing in Berkeley and then in San Francisco Bay’s Ocean Park, embracing figurative and landscape painting at a time when abstraction was the way to go. He wasn’t much of a draughtsman, but boy could he paint. He was an American fully conversant with 19th-century French painting, but who particularly absorbed the lessons of the great decorative modernist Matisse. And what a stunning hang in the Royal Academy’s Sackler Galleries.

Defining Beauty: The Body in Ancient Greek Art, British Museum

The Greeks, they knew a thing or two about beauty. They pondered its laws and mathematical dimensions, but somehow they produced sculpture that was more than the sum of its precisely measured parts. Defining Beauty was a superbly illuminating exhibition looking at the evolution of idealised realism in classical sculpture, with figures in marble and bronze that highlighted movement and the dynamism of the human body. What’s more, this was an exhibition that managed to make it all seem so fresh, so vividly alive, yet it all remained just a bit wild and strange.

Bottom of the class

Carsten Höller, Hayward Gallery

Slides, swings, roundabouts. Depressing. Go to a fun fair.

Two to put in your diary right now

He was an ousider, a rebel, an artist with a Jesus complex – the man of many masks is bought to you by fellow Belgian Luc Tuymans. From 29 October.

Robert Rauschenberg, Tate Modern

Big, dirty, hulking combines – the late, great American Duchampian and Pop precursor has an overdue survey. Yes. From 1 December.