The beguiling tone poems of an American artist

Whimsical, twee, sentimental. For those who love Joseph Cornell’s boxes, it’s hard to imagine that there are those who just don’t. “What? You mean you don’t like Cornell’s boxes because you think they’re whimsical? Twee? Sentimental?”

These rare people include one or two art critics I’ve known, and the incredulous reaction is my own. But he could be all of those things, of course; and as Robert Hughes reminded us on the occasion of Cornell’s 1980 survey at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, “There is a treacherous line between sentiment and sentimentality, particularly in [Cornell’s] evocations of his Edwardian childhood.”

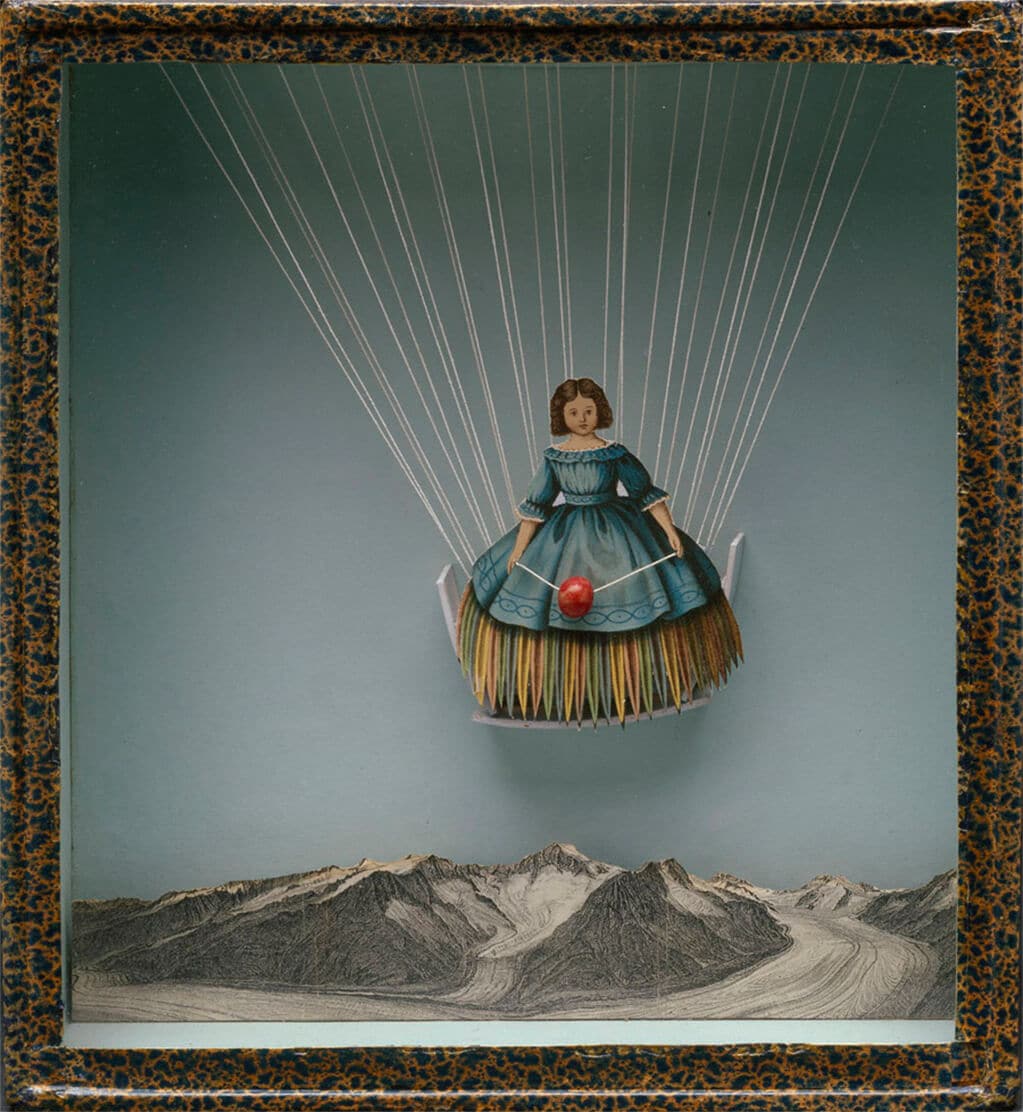

In the Royal Academy’s survey that treacherous line only occasionally comes into focus. A cut-out girl (pictured), serene, weightless, borne up on white cotton threads as she daintily floats over the Alps in crinoline that echoes the shape of a hot-air balloon, is surely one such piece that skirts that line and wobbles. The work was made in homage to the dancer Tilly Losch, one of several of the artist’s pashes on ballerinas and stage starlets. And often these are the least successful of his works.

Still, it’s an exquisite eye for form and juxtaposition that steers us clear on the whole, and even when it doesn’t there’s nothing cloying about it. This is sentimentality that isn’t heavily perfumed. It scents the air; it won’t choke you.

And what of the much talked of absence of sex that Hughes also drew our attention to, despite all those evocations of the divine, the sensual but untouchable, female? Cast your eye back to the balloon girl, and the cherry red bead dangling by a string between her fingers. Does it hint at the thrillingly Freudian? The darkly suggestive? Sex and surrealism went hand in hand for European artists such as Duchamp and Max Ernst, the murky, subterranean passions of the unconscious the meat and drink of that movement, to which Cornell was attached through friendship and influence.

Pharmacy, 1943, predating Damien Hirst by five decades; courtesy The Joseph and Robert Cornell Memorial Foundation

And yet Cornell seems decidedly pre-sex, not in the sense of its complete absence, but in its fragile burgeoning, in its on the cuspness, its lack of maturity. Neither absent nor repressed, the hints of sex to be found in Cornell’s juxtapositions, as well as in his obsessive romantic longings at far remove, present a state of perpetual pre-adolescence.

Cornell’s biography is well enough known not to recount it at length here. Suffice to say, here is an artist who wandered the cosmopolitan centres of Europe – encountering a refined fairyland – in his mind, but who’d travelled no further than Maine, and had apparently never spent a night away from home. He was not an outsider in the sense that he genuinely stood outside the art world, for he had many an acquaintance within it and a high-profile New York gallery to represent him. But in a very real sense he still stood outside it – emotionally rather than artistically dislocated. However, he also had a sophisticated insider’s insight into his work, once writing that he wasn’t interested in expressing the “black magic” of the Surrealists, but in cultivating “white magic”.

The best pieces are the cabinets of repeated motifs: the white grids of his “Dovecoates” series, with their sequence of balls or wooden cubes; and his “Medici” series, where we find a tiny inky portrait, times 20, by a follower of Caravaggio, accompanied by 20 inky balls. The inky balls somewhat suggest the perfect, pared-down Mannerist head of the subject, which in turn resembles an egg in its shell. One thinks also of Koons’ weird couplings of blue balls and classical statuary and Warhol’s repeated inky screenprints. The Pharmacy cabinets, too (see picture), with their vials of coloured pigments, shells, butterfly wings, which predate Damien Hirst by five decades. None, however, express the lyrical “tone poetry” of Cornell.

What speaks powerfully is a psychological dimension to the work. It would be odd not to note this, for that strange sense of dislocation and arrested development feel so present.