Masterful and pioneering: the American artist’s kinetic sculptures

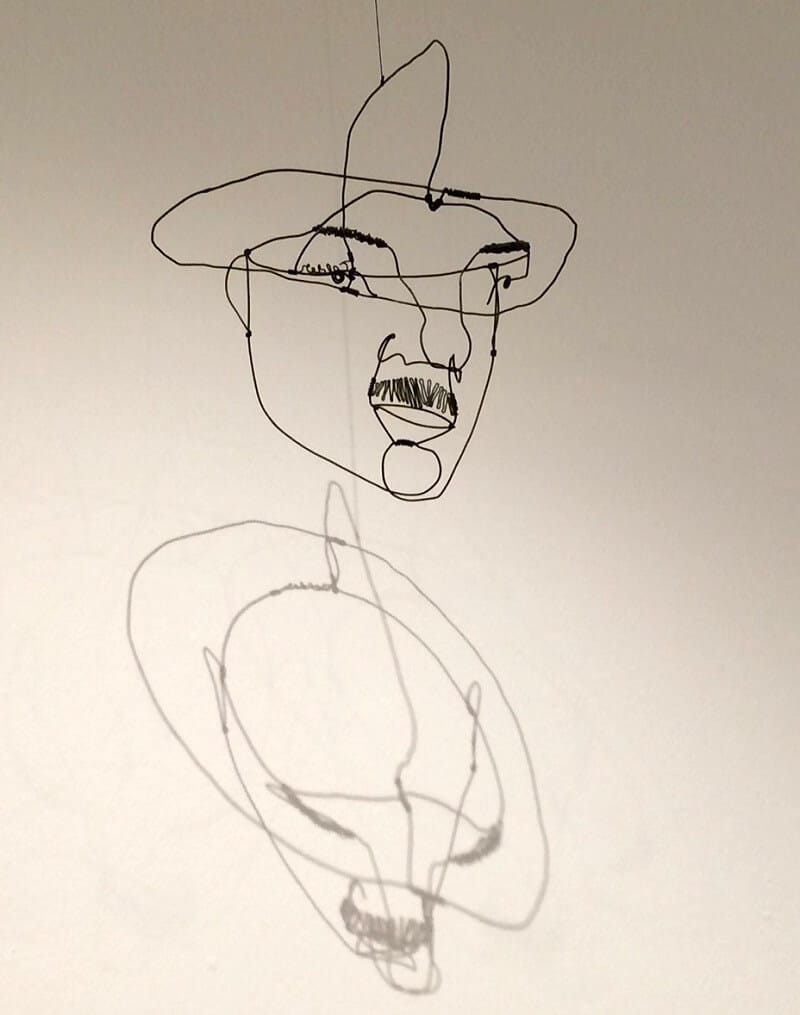

Sculpture that moves with the gentlest current of air! Sculpture that makes you want to do a little tap dance of joy! Or maybe the Charleston – swing a leg to those sizzling Jazz Age colours and shapes and rhythms. Look, that’s the queen of the Charleston right there – the “Black Pearl” of the Revue Nègre, Josephine Baker. She’s a freestyle 3D doodle in space, fashioned out of wire: spiral cones for pert breasts, that sinuous waist described by a single serpentine line. What a callipygous shimmy. And who’s that with the Chaplin moustache? Why, it’s the head of Fernand Léger (pictured), casting anamorphic shadows on the wall. Léger not only put the glam into machine-age modernism but the immaculate sheen of pneumatic Tubism into dour Cubism.

Alexander Calder was an American in Paris, depicting the characters he met in the city’s adventurous avant-garde circles. These “open” linear sculptures, hanging off walls and suspended from ceilings like coat hangers, came to be known as his “drawings in space”. With lengths of wire he had the fine facility of Matisse for agile, voluptuous, volumetric form.

Arriving in Paris in 1926, a relative late-starter at 28, he soon, however, became the P.T Barnum of the artistic elite. Carrying his valises filled with tricks and sophisticated toys – circus figures fashioned from wire, wood, cork stoppers, clothes pegs and rubber and fabric – his travelling Cirque Calder was taken from one fashionable salon to another, and performed for friends, including Duchamp, Miró and Mondrian.

Mondrian’s by-now bitter rival Van Doesburg was especially enchanted, and though it was Mondrian who would ultimately shape the younger artist’s future, Duchamp’s rotating spirals and Miró’s colourful biomorphic forms certainly both had their impact. One even thinks too of Klee’s exquisite and touchingly comedic Tightrope Walker when it comes to Calder’s finely balanced pieces (Calder called one 1936 work – its delicate wire loops and spirals balanced precariously on a wire strung between two tripod-legged forms – Tightrope).

From his earliest beginnings in Philadelphia, Calder’s future seemed set. His mother was a painter, his father and grandfather (both called Alexander) were successful, even eminent sculptors (one of his father’s most prominent commissions was a stone carving of George Washington, graced by the figures of Wisdom and Justice, on Washington Square Arch). But when he came of age Calder, counter-intuitively, left behind his childhood fascination with art-making to train as a mechanical engineer. After graduation he moved between various jobs, settling for a while as an illustrator. By the time he left for Paris, equipped with his engineering know-how, he was ready to create the complex mechanical circus that would intrigue his artistic friends.

Out of the joyously ramshackle circus came the intricate wire sculptures, first of acrobats and strongmen, then, as we find in Tate’s beautifully designed, spacious survey, his quirky portraits. We see how he moved from a folksy junkyard aesthetic to his more refined and airy sculpture-drawings. But it was only when he visited Mondrian’s Paris studio for the first time that Calder’s breakthrough occurred, and it steered him away from the figurative to his elegantly restrained, hanging abstract forms. Calder was struck by the coloured cardboard rectangles that Mondrian attached to his walls as compositional aids. In fact, he even suggested it might be interesting to make them move. Au contraire. Mondrian replied that his paintings were already “very fast”.

What finally came about wasn’t “very fast” at all, but brightly coloured motorised globes within circular frames that moved slowly, suggesting planetary motion, or more spikily geometric pieces suggesting cosmic constellations. When A Universe, 1934, was first exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Calder was told that Albert Einstein stood watching it for 40 minutes as it went through its 90 cycles of movement before it began to repeat itself. A Universe is one of the very few works stuck behind glass in this exhibition, and it’s now far too fragile to set its motor. Instead we have films of some of the mechanised pieces in elegant flow.

But even with Calder’s later mobiles (it was Duchamp who invented the term for them; “stabiles” describe those fixed to the floor) the natural world is never far away. The matt-black Vertical Foliage, 1941, hints at a dancing, twirling silhouette of a branch with sprigs in full leaf. And there’s the even more surprisingly sombre Black Widow, 1948 (pictured), its paddle-shaped black fronds punctured like Swiss cheese. This last, a rare loan, is a 3.5-metre sculpture which normally hangs in the central space of the Institute of Architects of Brazil in São Paulo. Here it hangs alone in the final room of this rich and revelatory survey.

There are none of Calder’s rather muddy early single-media paintings in this exhibition – he was certainly never going to be an innovative artist on canvas. But his sculptural evolution, as we see, was both masterful and pioneering.