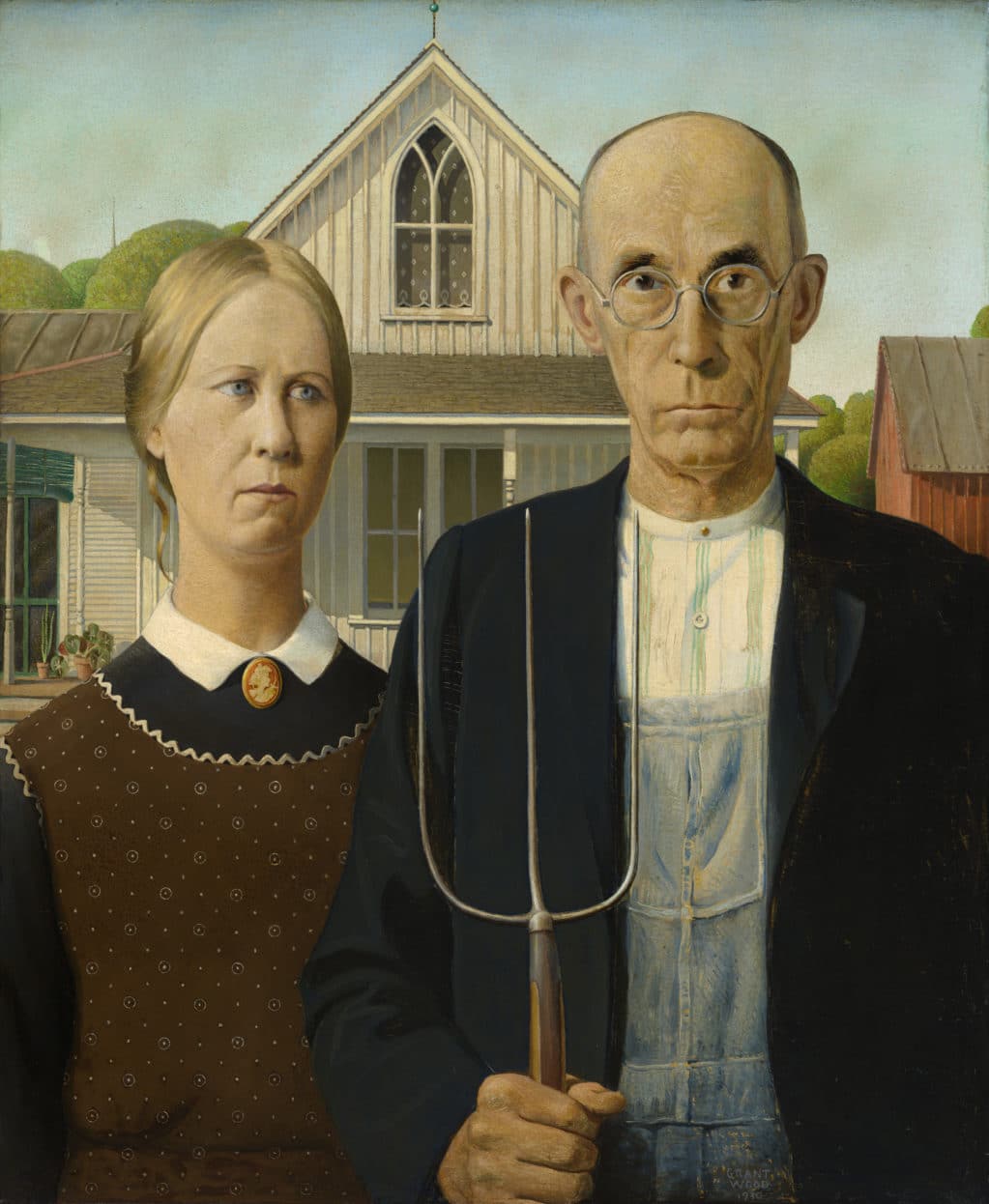

Is Grant Wood’s famous painting serious or comic? It is this ambiguity that has helped made it one of the most parodied images in art history?

Could the painting possibly be a paean, even in its mildly ironic way, to small-town America, to those simple, decent values ascribed to the US heartland? Or is it, as so often assumed, a straightforward satire? Is its intention to hold up to ridicule the small-minded provincialism of the American Midwest, and its hostility to outsiders?

Grant Wood’s American Gothic is a painting that’s puzzled generations who’ve stopped to wonder at the real meaning behind it. We all know it: a close-cropped portrait of a grim-faced Iowan couple in front of their scrupulously neat, gothic-arched, timber house – in a style also called Carpenter’s Gothic for its homespun take on Victorian Gothic architecture, and for which the painting is named.

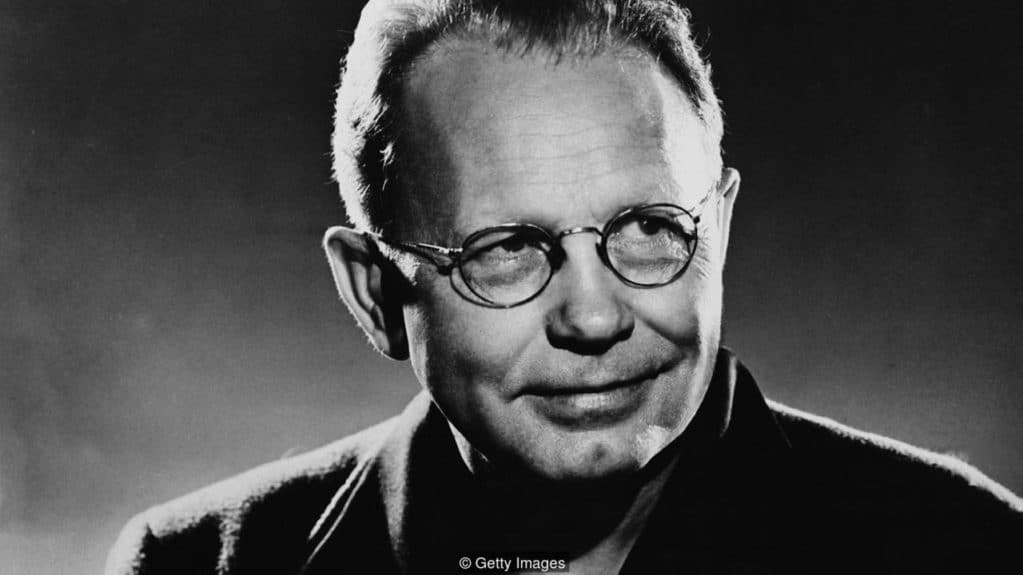

It was painted in 1930, when US artists were inspired to paint realist scenes of rural America during the Depression, rejecting European modernist influences for a decidedly home-grown, often folksy authenticity, in a style that became known as Regionalism. This February, the painting will travel outside of North America for the first time, as the centrepiece of the Royal Academy in London’s exhibition America After the Fall: Painting in the 1930s, where it will be shown alongside both Regionalist and modernist works.

The striking couple are identified either as a homesteading farmer and his wife, or as a daughter with her taciturn and over-protective father. Wood’s sister, Nan, who posed for the picture, always insisted the two were father and daughter, perhaps finding the age gap too unseemly. The relationship has always remained interestingly ambivalent.

Unlike her elder companion’s fixed stare, the woman doesn’t meet our gaze, but, slightly squint-eyed under that furrowed-brow, glances off to the side. Her expression is actually difficult to determine. She looks sorrowful, or perhaps fretful, or perhaps stoic, or even perhaps simply sour-faced, though her straitlaced Puritan primness is subtly undermined by an escaping coil of hair at the nape of her neck. As if holding guard against those anticipated intruders – as likely as not, protecting his daughter-wife’s virtue, though she doesn’t seem particularly happy about it – the man grips a pitchfork in a warrior-like fashion. And it’s this devilish motif that lends the work its ambivalent, uneasy comedy. Without it, the mood of American Gothic would certainly feel a little more plaintive, and a little less like the theatrical tableau it is, for the scene isn’t in any sense ‘real’. Everything about it is an artful set-up.

First of all, Nan never actually posed with the man in the picture, nor are they in any way related. Wood had spotted the house during a drive to the town of Eldon in Iowa. It immediately gave him an idea. “That idea was to find two people who, by their severely straight-laced characters, would fit into such a home,” he later explained. So the impetus for the painting is a story-telling one, and a resolutely anti-modernist one.

Wood came to paint the picture in his late thirties, having, in his twenties, spent some time studying painting in Paris, the centre of avant-garde art, and in Munich. Having become familiar with modern painting, he himself had painted in an Impressionist manner, but on his return to the Midwest he was soon to reject all he had seen and learned. He would adopt the detailed, realist style of 15th-Century Flemish painter Van Eyck, and he would embrace Regionalism, but with his own character-driven twist. Despite going back to earlier European traditions, Wood really felt that what he and the Regionalists were doing was finally liberating American art from cultural colonialism, which is something only the later Abstract Expressionists, who embraced modernism full-tilt, would be championed for doing. American Gothic has become an American icon, but Regionalism itself would never be thought of as a significant movement in the canon of US art history.

Wood must have learnt all about plein-air painting in Paris, but the couple in American Gothic were painted separately, and neither sitter was painted in front of the house. The farmer, as you might have already guessed, isn’t actually a farmer, but a certain Dr Bryon McKeeby, a well-to-do dentist from Cedar Rapids, where Wood lived with his mother and sister. The couple’s clothing too has been carefully handpicked by the artist, and the woman’s dress is distinctly old-fashioned, so the first viewers of the painting would have quickly noted the air of nostalgia – though, with the painting’s hard lines and surfaces, there’s little accompanying sentimentality.

In addition, both their faces, Nan’s in particular, have been thinned and elongated, as has the prominent gothic window and roof. And, if you look carefully, you might even detect something funereal about the scene, beyond the tombstone features of the couple. It’s subtly suggested by the woman’s primly buttoned black dress, which she wears under her rickrack-trimmed apron, in the man’s smart black overcoat, which contrasts with his overalls, and by the drawn blinds of the window below the arched one. Why are they closed on such a bright day?

Regarding the painting’s comic tone, Wood himself gave contradictory accounts. “There is satire in it,” he once said, “but only as there is satire in any realistic statement.” Perhaps it is this ambiguity that has made the painting endure as the most iconic, and of course the most parodied, in US history. Gertrude Stein, insisted that the painting was a “devastating satire.” The modernist writer and avid collector of Picasso and Matisse even went as far as to describe Wood, apparently without a hint of irony herself, as the “foremost American painter.” Others despised it for its ‘fake-folkery’. Clement Greenberg, the towering art critic who championed Jackson Pollock, also chipped in and opined that Wood is “among the notable vulgarisers of our period.”

As with the Louvre’s Mona Lisa, which has also had its share of cartoon iconoclasts, American Gothic is a star attraction at the Art Institute of Chicago, where it’s been since winning a bronze medal and $300 in a painting competition the year it was painted. But its inclusion in the collection wasn’t immediately welcome. An official at the museum snortingly described it as “a comic Valentine”.

With the advent of mass media the two characters have taken on a life of their own, appearing in everything from TV commercials for cornflakes and several US sitcoms, to a cameo appearance as a pair of creepy puritans in The Rocky Horror Picture Show. And there’s hardly a president and his first lady whose heads haven’t been transposed onto the pair. Most recently, in the UK’s Spectator magazine, Donald and Melania looked impassively out as the house and barn behind them burned.

One of the most powerful riffs on the painting doesn’t have any comic undertow, however. Instead, Gordon Parks’ 1942 photograph of Ella Watson, a black office cleaner, makes searingly visible the previously invisible.

Watson, who stands on her own, is framed by a huge broom, which she holds, and a mop, to the side, in place of the male figure, which now takes on a ghostly absence. The backdrop isn’t a house but the US flag. (Watson’s job was to scrub the floors of a federal government building in Washington DC – she is at work). Wearing round-rimmed spectacles, her painfully thin, androgynous figure appears to stand in for both characters in Wood’s painting. Subverting the whiteness of that enduring painting, Parks’ photograph, which later appeared on the cover of the Washington Post, is an astonishingly poignant image. (Incidentally, Parks himself would later become a pioneering director of the first Blaxploitation films and in 1984 made the first film adaptation of 12 Years a Slave.)

It is the slipperiness of American Gothic that makes it continue to resonate so powerfully. The painting is ambiguous enough to speak to each generation on their own terms.