A fine retrospective of a conceptual artist whose work offers more light and shade than her spoken words

Addressing a crowd of journalists gathered at the press launch of her major retrospective at the Guggenheim Bilbao, Yoko Ono begins by telling us how cynical she is. It’s quite a claim considering it’s just about the last thing you’d ever think to call her. Perhaps she’s finally tired of being dismissed as a naive idealist. But no, it’s just a roundabout way for her to express her astonishment at the extraordinary architecture of Frank Gehry’s glinting, titanium-clad masterpiece, which opened 16 years ago in this Basque city of northern Spain. Being “naturally cynical” she hadn’t, she said, quite believed any of the claims made for it until she saw it for herself. Now she wants to tell us that it’s the best museum in the world.

Ono has a way of beginning stories that you imagine can only end on a negative note. But, by some cognitive sleight of hand, a kind of irrepressible Panglossian optimism prevails. Another begins with her musician/producer son Sean Lennon. One time, she says, he came to see her at her Dakota apartment in Manhattan and during the whole visit she just couldn’t get him to talk to her. He could, she says, barely raise his eyes from his smartphone.

Naturally you’d think this would be a cue to lament society’s unhealthy attachment to technology at the detriment of nurturing proper relationships. But no, within the blink of an eye, she’s done a complete turnaround: she’s telling us how technology and social media is an extraordinary thing that will bring world peace because we’re all “communicating with each other now”. It is, she says, an opportunity to build a better world. I’d like to say her optimism is infectious, but you detect something closer to cognitive dissonance.

I’m wondering to what extent this is reflected in her work. I’m wondering just how much this darker, or at least more uneasily ambivalent, side to her manages to slip through unawares, cutting through all the talk of universal love and peace to produce layers of meaning which are more questioning, more unruly and more difficult to neatly package.

Some of her more recent work does nothing to counteract an overweening whimsy. I find her series of Wish Trees, in which she invites visitors to jot down their dreams and wishes on a piece of paper which they then hang on a tree, largely uninteresting as art. I find her Smilesfilm (which is not in this retrospective) in which she invited everyone on the planet to upload pictures of their smiling faces, a bit vacuous. But that doesn’t mean I find Ono uninteresting as an artist, nor her best work without power and resonance. And this retrospective provides an indepth insight more layered, more nuanced, more subtle, and finally more troubling, than either of those pieces.

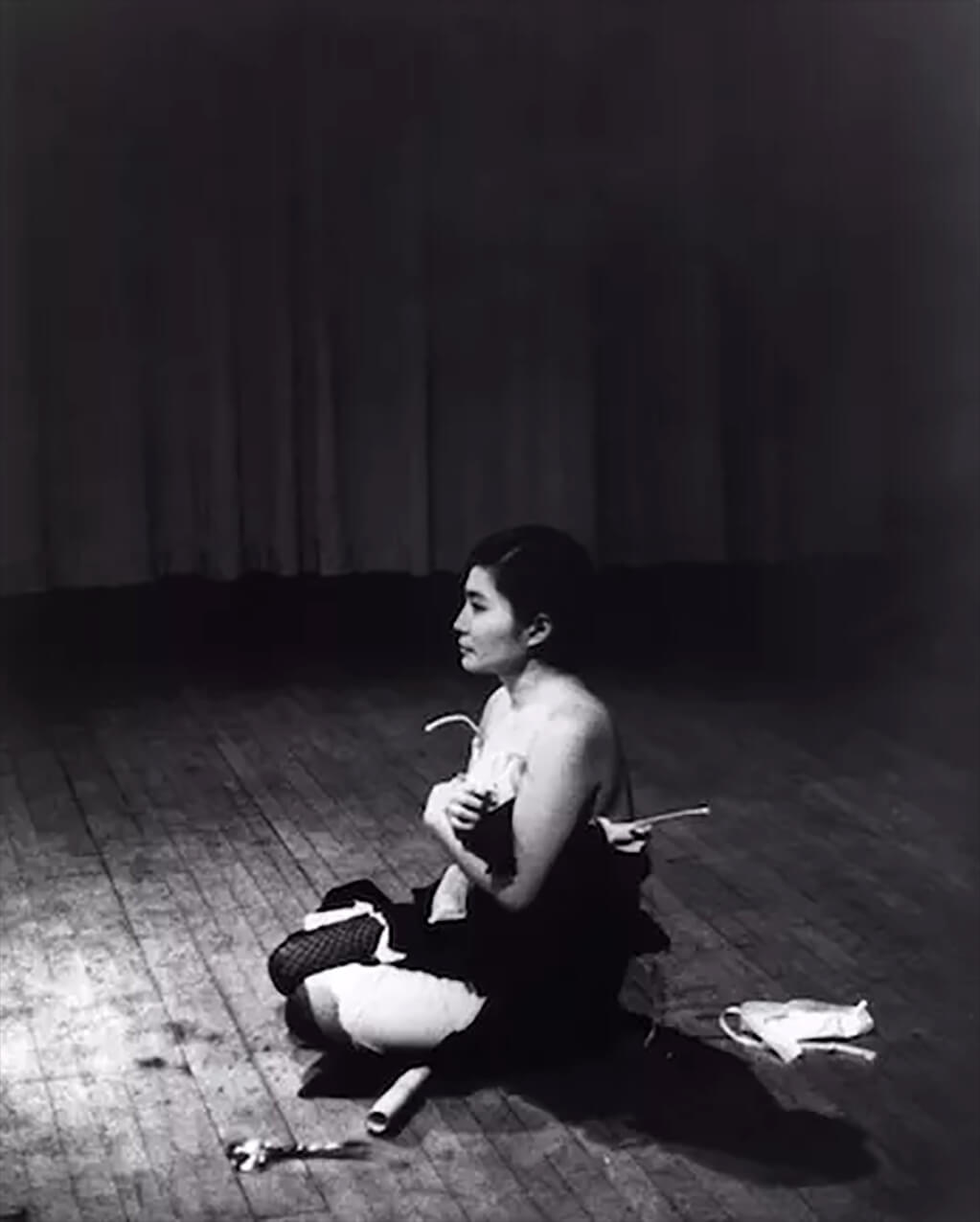

Ono’s most famous work, and certainly among her most powerful, is probably the 1964 Cut Piece, first performed in Tokyo, then at Carnegie Hall in New York in 1965 (pictured). For this, she invited members of the audience, both men and women, to cut through sections of her dress with a pair of scissors as she sat quietly on the floor of the stage, her expression impassive throughout. The New York audience behave respectfully, leaving her bra and knickers intact. Yet as we see her dress tugged and pulled by a succession of strange hands with sharp implements, the expectant erotic charge gives way to something not just more troubling, with its potential for violence, but more searingly poignant. Her passive surrender, her vulnerability, become a universal metaphor. We may view the piece as pioneering feminist art – although Ono has said that this is not really where the work began for her, but rather as an expression of Buddhist feminine acceptance – but I think of it as both a work about gender and as something which goes beyond the specifics of gender. It’s a piece of distilled Beckettian poetry.

The exhibition’s title, Half-A-Wind-Show, is named after her solo exhibition at the Lisson Gallery in 1967, where she first showed her installation Half-a-Room, a living room in which all the objects are shorn in half – half a female shoe, half a male shoe, half a bookshelf, half a glasses case, etc. Perhaps it’s a rather blunt statement about lives half-fulfilled or half-lived, but nonetheless it’s a visually strong piece. A similar installation, Balance Piece, 1997/2010, is a display of domestic appliances that hang mid-air, “pulled” by the giant magnate on the other side of the wall. Her work seems to anticipate many of the strange domestic appliance installations of Mona Hatoum.

Here too is the ladder that John Lennon climbed in Ceiling Painting, Yes Painting, 1966, at the groovy Indica Gallery in Mayfair. Reading the tiny inscription “Yes” on the ceiling with the dangling magnifying glass provided, made him feel like he’d found a kindred spirit even before they’d met. It was this that made Lennon, according to legend, bite the apple on the Plexiglass plinth nearby.

Deeply evocative but less well-known is Wrapping Piece for London (Wrapped Chair), 1966, which immediately reminds me of one of Sarah Lucas’s abject chairs with stuffed tights. The chair is bound tightly in gauze and painted white. There are hints of a feminine form in the bulges beneath the ragged cloth. It’s an incredibly strong piece.

The following year Ono managed to wrap one of the Trafalgar Square lions, an act reminiscent of what Christo and Jeanne-Claude, those monument-wrapping doyens, were already doing. She only got away with it because she said she was making a film (such is the power of the media to trump authority). In the photographs you see the curious crowds gather to witness this politically subversive action.

Another wrapping piece is far more visceral and violent, and seems to form part of a personal memorial. Sack with Baby, 1993 is part of a series of objects from Family Album (Blood Objects), in which bronze casts of ordinary objects sit on a glass plinth. The baby-shaped sack is splattered with blood-red paint, as are all the other objects. On a glass plinth right next to Sack with Baby are bent coat hangers, similarly splattered.

In a later work called Vertical Memory, 1997, you read of her abortions in a compelling text piece outlining significant episodes of her life over which a man has presided in a position of authority, including the doctor who performed her abortions. Above each of these short, stark statements we find the same cropped and blurred, sinister-looking photograph of a man in glasses looking down. The image is, in fact, an amalgam of photographs of John Lennon, her son Sean, and her father, three of the most important men to have featured in her life. But there’s no tenderness to the piece. Ono presents a story in which her actions are contingent in each case on the male authority figure, except for the final piece in which she rejects a given instruction.

Among my own favourite works are White Chess Set, 1966/2013, a game that is impossible to play since all the chess pieces are white, so there can be no winners, no losers, no stalemate; Touch Poem, No.5, 1960, an eloquently tactile book featuring coils of human hair; and the Museum of Modern (F)art, 1971, for which Ono took out in an ad in the Village Voice to announce her exhibition at MoMA. Accompanying it is an amusing film in which random New Yorkers are asked if they’d seen it yet, though the exhibition didn’t actually exist and the ad was placed only to highlight the fact that so few female artists got to show within its hallowed walls.

The retrospective is curated by John Hendricks, an expert in Fluxus, the Sixties conceptual art movement of which Ono was a leading member, and it features some 200 works. In parallel to her career as a visual artist, Ono has recorded countless albums and performed live in a multitude of collaborations, most recently with Lady Gaga, Iggy Pop and Antony Hegarty. The filmed concerts, along with her recordings, make up the last room of the exhibition. Her voice – it’s admittedly thin and she seems not to have too much vocal control, but mostly she makes rhythmic plosive sounds – may not be music to everyone’s ears, but Ono is a fearless and generous artist and this is a fine retrospective of a career spanning over 50 years.