The writer was profoundly influenced by art and in turn influenced artists.

A sci-fi special would be incomplete without the profoundly influential figure of JG Ballard, a writer who, when he began his career in the late Fifties, fully subscribed to the notion that “sci-fi is the literature of the 20th century.” Unlike the “Hampstead novel,” he once said, “the sci-fi novel plays back the century to itself.”

But as much as he had embraced it, no one genre could really contain him. He was sui generis, and something of a visionary with it, acutely alive to the evolving hyper-real present and its dystopian possibilities. Environmental catastrophe, mass media, the fetishization of technology and consumerism, the physical, hyperrealised landscape of modernity – all these became for him urgent topics to address in fiction at a time when the British literary scene had barely noticed it was in the 20th century.

And his influence on other artists, particularly visual artists – unsurprising, since he himself was a profoundly cinematic writer – has been immense. Writing his obituary in 2009, Martin Amis wrote that Ballard had “very little interest in human beings in the conventional sense (and no ear for dialogue); he was remorselessly visual”.

It was the twinned inner “mindscapes” of Surrealism and psychoanalysis that made their enduring impact on Ballard very early on. He was drawn to the disquieting dreamscapes of De Chirico and Magritte and particularly to the highly eroticised paintings, with their somnambulant nudes and Freudian couplings of Eros and Thanatos, of Paul Delvaux.

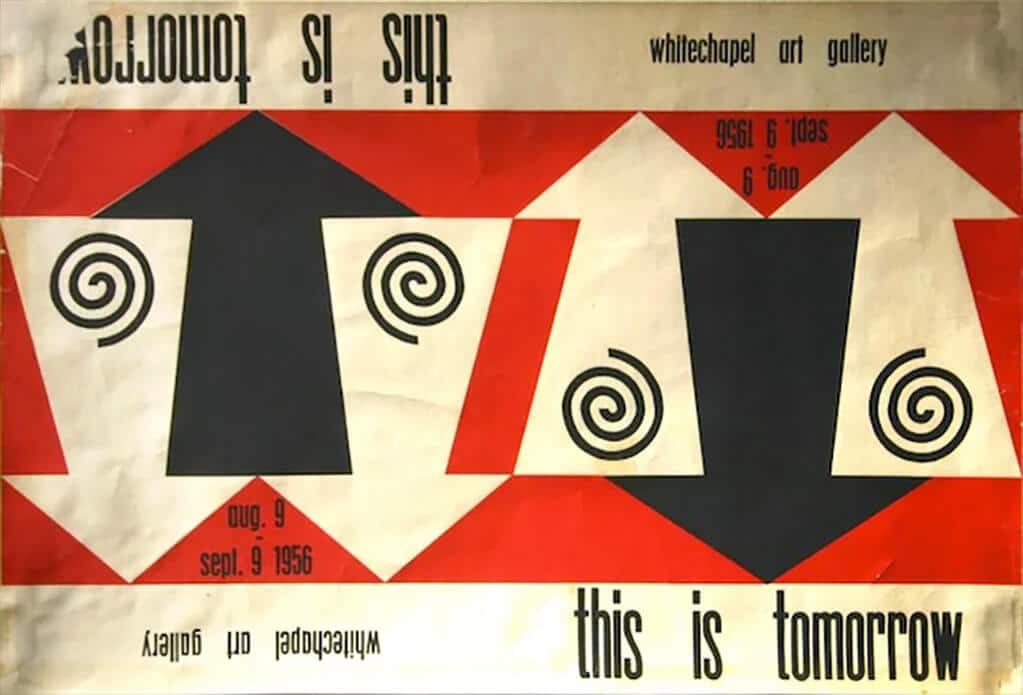

And when Ballard encountered British Pop art for the first time his excitement was considerable. He visited This is Tomorrow, the groundbreaking 1956 Whitechapel Gallery exhibition, featuring Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hamilton, and found that visual art was doing something British literary fiction wasn’t: it was addressing the world as it was being lived and experienced right now.

Ballard responded by making collages himself, connected to themes that were beginning to preoccupy him in his writing. Much later, in 1970, no doubt with Warhol’s Car Crash screenprints of the early Sixties fresh in the mind, he organised an exhibition of crashed cars at London’s avant-garde New Arts Lab, simply called Crashed Cars. The crushed vehicles were displayed without commentary and, as might have been anticipated, excited outraged responses and acts of vandalism. His novel Crash, in which the dark erotic impulse is tied to the pursuit of death in a car crash, followed in 1973.

Ballard’s striking visual sensibility has, in turn, proved an enduring influence to many younger artists – from French artist Dominique Gonzlez-Forester, whose ninth Tate Modern Turbine Hall installation suggested a flooded, swampy post apocalypse in the middle of London (a nod to Ballard’s 1962 novel The Drowned World, among other science fiction scenerios) to British artist Marc Quinn’s prints of dizzyingly hyper-real, colour-saturated and lushly overgrown botanic gardens (naming one series Drowned World).

More directly, Tacita Dean’s 2013 film JG explored Ballard’s fascination with artist Robert Smithson, and was inspired by her correspondence with the writer in his last years. Their letters explored the connections between Smithson’s great earthwork Spiral Jetty, 1970, built on the north-eastern shore of Utah’s Great Salt Lake (pictured below), and Ballard’s short story The Voices of Time, published 10 years earlier, in which the main character builds a mandala in a dried saline landscape. The collection featuring this story was found among Smithson’s belongings after his death in a plane crash in 1973. Like Ballard, Smithson was fascinated by the idea of entropy, and Ballard was in turn fascinated by Spiral Jetty, though Ballard’s twin obsessions encompassed psychological as well as environmental disintegration.

One might think of many other artists absorbed by Ballardian themes and ideas. Shortly after the writer’s death, a group show of Gagosian artists at Gagosian Britannia Street, including Ed Ruscha and the Chapman brothers among others, explored connections in homage to the late writer. But one artist whose work I think of more readily is Roger Hiorns’ Seizure, his glittering blue crystal growth overtaking the interior of an abandoned council flat in the Elephant and Castle. In Ballard’s 1966 post-apocalyptic novel The Crystal World, a mysterious force is mineralizing every surface of a jungle, including its animals. This eloquent environmental updating of the King Midas story seems poignantly fitting for an age in which anxiety and moral uncertainty haunt us.