Work, Build and Don’t Whine explores the iconography of women in the 20th century and how their roles changed from revolution to revolution.

It’s one of the most famous artworks of the Stalinist era, but few westerners would recognise it quite as readily as that unrealised avant-garde icon of the Bolshevik revolution, Tatlin’s Tower. Vera Mukhina’s 78-ft-high steel monument, Worker and Kolkhoz Woman, which has been celebrated on stamps and is the logo of Mosfilm, Russia’s oldest surviving film studio, was created to crown the Soviet pavilion at the 1937 Paris World’s Fair. It depicts a heroic couple whose arms are raised in unison, a man holding aloft the hammer, while a woman raises a sickle above her head. It is a prime example of social realism, the style imposed by Joseph Stalin as one ideologically befitting the art of the proletariat.

Mukhina, who died in 1953 (the same year as Stalin), was a winner of five Stalin prizes. Worker and Kolkhoz Woman was her most celebrated work, and a bronze model – on loan from Moscow’s Tretyakov State gallery, will feature in the exhibition Superwoman: Work, Build and Don’t Whine, at the Gallery for Russian Arts and Design (Grad). The exhibition, ambitious in its scope, explores the iconography of the Soviet woman from the October Revolution in 1917 to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Mukhina’s depiction of a proletariat man and woman, side by side and sharing equally the symbols invested in the ideals of Soviet communism (although note, it is still the man wielding the forceful hammer), encapsulates the drive for women to be fully engaged in building the communist state, alongside men. In the words of Stalin’s predecessor, Vladimir Lenin, in 1919: “To effect her complete emancipation and make her the equal of the man, it is necessary … for women to participate in common productive labour. Then woman will occupy the same position as men.” Of course, as the exhibition reminds us, the reality continued to be quite different. Moreover, reforms realised under Lenin, such as legalised abortion, were reversed under Stalin, although women’s access to higher education and entry into professions such as engineering was encouraged with zeal under Stalin’s five-year plans.

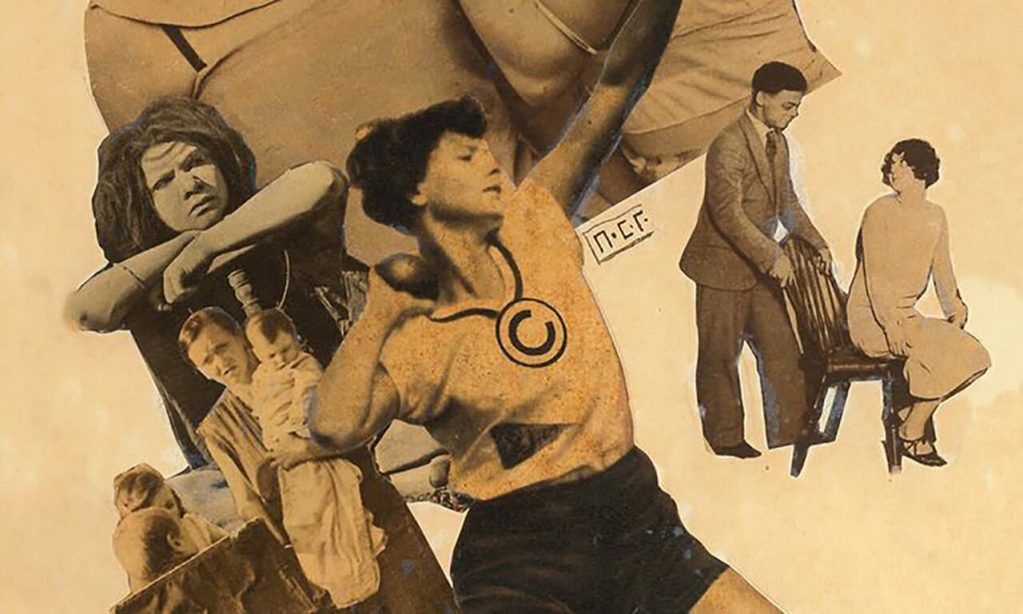

The title of the exhibition is taken from a poster by Aleksandr Deyneka, one of the leading proponents of Soviet social realism and an artist who was as decorated with honours as Mukhina. Work, Build and Don’t Whine – a title that was not in the least ironic when the piece was unveiled – is a 1930 poster depicting a discus-throwing sportswoman, aglow in the foreground of a scene otherwise dotted with indistinct male athletes.

Stylistically, Deyneka is a far cry from early Soviet posters by radical avant-garde artists such as Alexander Rodchenko, who, in the 1920s, was the most celebrated photographer and graphic artist to emerge post-revolution, and who worked to spread the message of Bolshevism. Rodchenko’s most famous poster is his brilliant and much spoofed 1924 photomontage for the Lengiz Publishing House, in which a young woman with cupped hand shouts out, her cry captioned in beautiful modernist typography. Under Stalin, Rodchenko was accused of “formalism”, an accusation that beset many avant-garde artists in the 1930s, and his work was duly censored. Artists such as Deyneka fulfilled the propaganda brief, but their posters, shorn of radicalism, are inevitably dull in comparison.

Rather than showcase the best of Soviet art, Grad highlights the art that promoted the idealised roles expected of women in their duty to the state; to show how these expectations shifted and changed, and how the unique burdens placed on women, as mothers and as workers, were heightened by rapid industrialisation and the long years of the cold war.