Folk art from Africa and the Pacific changed the modern world by pushing Western artists to be more confrontational

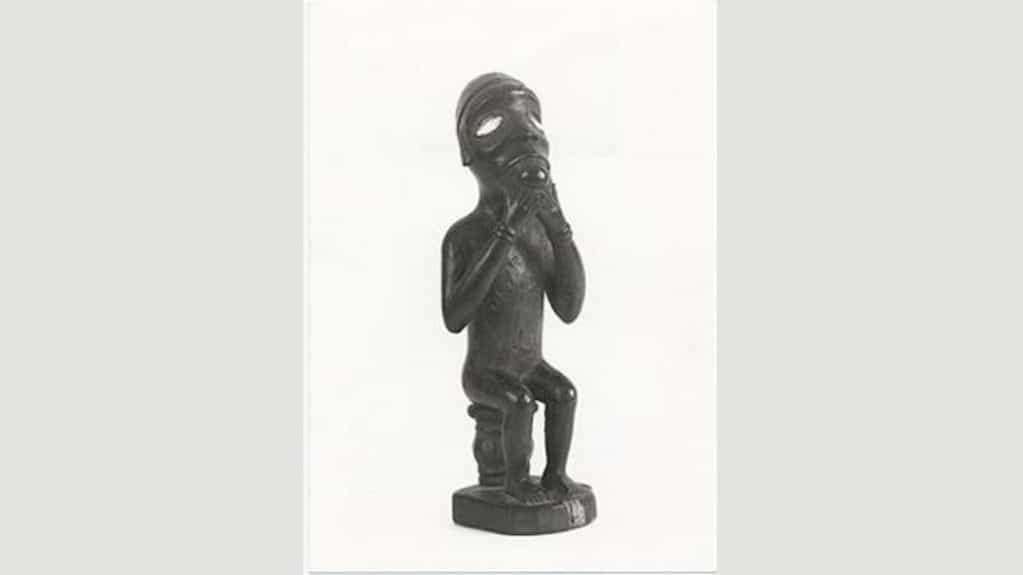

A small seated figurine from the Vili people of what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo was instrumental in the lives of two of the greatest artists of the 20th Century. The carved figure in wood, with its large upturned face, long torso, disproportionately short legs and tiny feet and hands, was purchased in a curio shop in Paris by Henri Matisse in 1906. The French artist, who liked to fill his studio with exotic trinkets and objets d’art, objects that would then appear in his paintings, paid a pittance for it.

Yet when he showed it to Pablo Picasso at the home of the art patron and avant-garde writer Gertrude Stein, its impact on the young Spaniard was profound, just as it was, though to an arguably lesser extent, on Matisse when the compact but powerful figure had fortuitously caught his eye.

For Picasso, his appetite whetted, visits to the African section of the ethnographic museum at the Palais du Trocadéro inevitably followed. And so precocious was the 24-year-old artist that it seemed that he had already absorbed all that European art had to offer. Hungry for something radically different, something almost entirely new to the Western gaze that might provide fresh and dynamic impetus to his feverish creative energies, Picasso became captivated by the dramatic masks, totems, fetishes and carved figures on display, just as he had with the Iberian stone sculptures of ancient Spain which he also sourced as material. Here, however, was something altogether different, altogether more dynamic and visceral.

When, after hundreds of preparatory paintings and drawings, he finally unveiled his breakthrough proto-Cubist masterpiece, the 8 sq ft Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, even his most avant-garde friends were shocked. Surely he had gone too far. What confronted them in his Montmartre studio, in that late Summer of 1907 (though the painting wasn’t exhibited publicly until 1916) was brutal and disconcerting. Five women, three of whom stare back at the viewer with huge, fierce eyes, were arranged in various confrontational poses and aggressively sexualised attitudes. The three women to the right have the smooth, though now distorted, features he took from Iberian carved heads, while the two ‘Africanised’ women to the left have the dark facial markings that resemble scarified flesh, or perhaps the texture and hue of roughly hacked wood. Their faces are all somewhat mask-like.

But it wasn’t just the small Congolese figure that had provided the spur and turning point for Picasso’s work – and you can see this figure currently in the Royal Academy’s exhibition Matisse in the Studio, along with other objects Matisse kept that informed his painting and sculpture. It was the companionable rivalry provided by this new relationship with the older French artist, for Matisse was, at that point, the far more experimental and radical artist – the leading Fauve, or ‘Wild Beast’.

Matisse had painted his multi-coloured, dream-pastoral Le Bonheur de Vivre in 1906, the year he bought the African figurine and the year the two artists met (and he was soon experimenting with his own ‘Africanised’ nudes), and Les Demoiselles was painted partly in answer to it. Picasso was intent on painting something even more radical and daring, a work that would leave its mark, which, for the last 110 years it certainly has.

But Matisse wasn’t the first artist to appropriate non-Western art. Primitivism, as it came to be known, was beginning to be embraced by artists in France at the end of the 19th Century, though some of its roots go back further, to the pastoral paintings of a golden age of the Neo-Classical period. And although fundamental to it, it wasn’t only non-Western artefacts that were of interest. Children’s art, and later the art of the mentally ill, so-called outsider art and folk art were significant contributions to the evolution of modernism, not just in visual art but in music too.

Back to basics

Matisse himself was always fascinated by the drawings of his own children and saw within them possibilities for the direction of his own work. That interest, too, was followed through by Picasso, who later famously remarked that, “Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once he grows up.”

What was taken from each category of art produced from these non-conventional sources, was a sense of spontaneity, of innocence, of a creative impulse not suffocated by academic fine art training or indeed by Western values, which were beginning to be seen in some intellectual and avant-garde circles as corrupt and decadent or as simply a spent force. The unmediated, the unspoiled and the authentic was what was now prized, and that included art that expressed the artist’s inner world, or what emerged in the 20th Century as the unconscious. Art, in other words, unfettered by the supposed artificial values of bourgeois society.

Though naivety and lack of sophistication was hardly true of either African art or art from other non-Western cultures, artists were struck by a directness, a pared-down simplicity and a non-naturalism that they discovered in these objects. But no thought was given to what these artefacts might actually mean, nor to any understanding of the unique cultures from which they derived. The politics of colonialism was not even in its infancy.

The Trocadéro museum, which had so impressed Picasso, had opened in 1878, with artefacts plundered from the French colonies. Today’s curators, including those of the Royal Academy’s Matisse exhibition in which African masks and figures from the artist’s collection appear, at least seek to acknowledge and redress this to a small extent. A similar effort was made earlier this year for Picasso Primitif at the Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, an exhibition exploring Picasso’s life-long relationship to African art. The sculptures, from West and Central Africa, were given as much space and importance as Picasso’s own work and one could appreciate at first hand the close correspondence between the works.

Meanwhile, the Art Institute of Chicago has an exhibition that looks at the creative process of an artist who was profoundly influenced by art from French Polynesia and who in turn was a particular influence on Matisse – those colour-saturated dream-like pastoral paintings again, including the early Le Bonheur de Vivre mentioned above. Paul Gauguin, perhaps the quintessential European artist to ‘go native’, first in Martinique, then in Tahiti, where he died in 1903 aged 54, had long felt a disgust at Western civilisation, its perceived inauthenticity and spiritual emptiness.

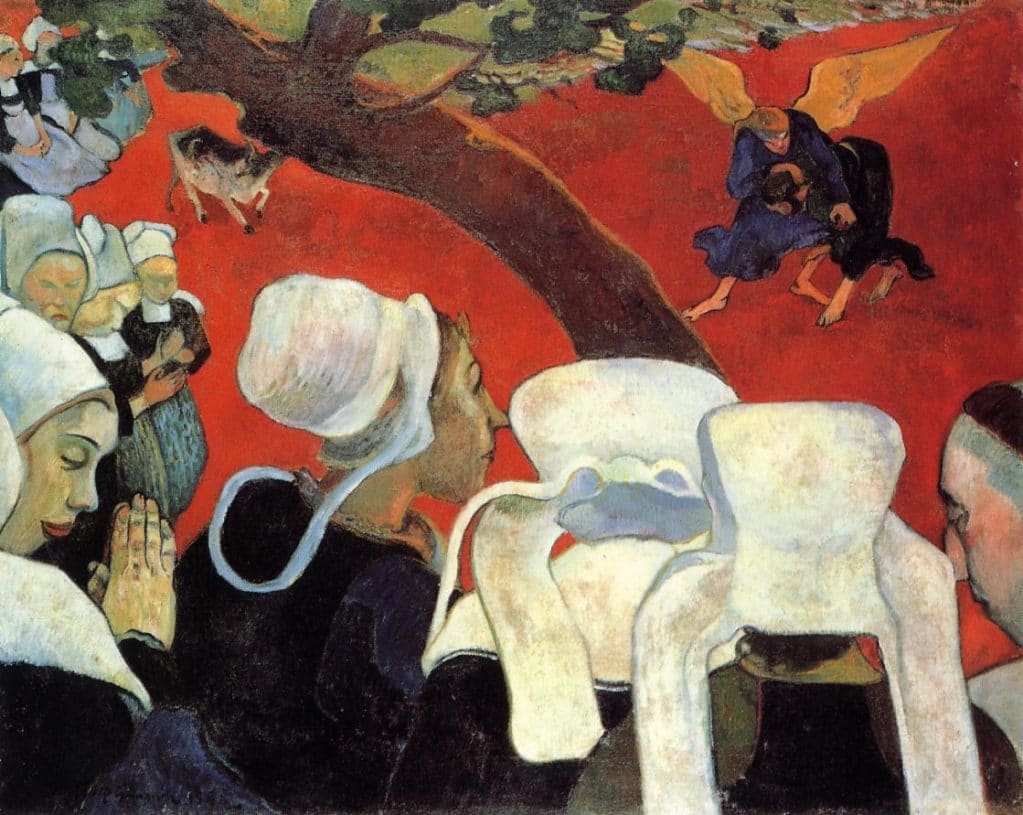

Gauguin, Vision After the Sermon (Jacob Wrestling With the Angel), 1988, Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

Even before he left European shores for good he had lived in an artist’s colony in Brittany, painting the deeply religious peasant women in traditional Breton dress. These paintings, such as Vision After the Sermon (Jacob Wrestling with the Angel), 1888, possess a rather unsettling and erotic sense of the numinous, as do his Tahiti paintings, with their piquant mix of sex and death. Gauguin: Artist as Alchemist shows us an artist fully immersed in the life from which his art was born.

The significance of non-European art on the avant-garde and on 20th-Century art modernism can’t be overestimated. It goes far beyond these three prominent artists, though all three were particularly instrumental in spreading its impact, from the Surrealists to Jackson Pollock. And even nearer our own time, seemingly long after the fascination with the primitif had been exhausted, the ritualised performance-land art of Ana Mendieta and the energetic postmodern faux-tribal paintings of Jean-Michel Basquiat saw that it certainly hadn’t.