The Medium is the message in Hamilton's political works.

Richard Hamilton, the true father of Pop art and spiritual descendant of Duchamp, is not a particularly prolific artist. Rather, he sticks to an idea and works on it over several editions and in different media, so that we get a large body of work repeating the same image in paint, in collage, in photography and in mixed media. For Hamilton, now 87, in so much of what he has done over the decades the key idea cannot be conveyed by a single unique work of art, because the key idea is often to do with the multiplicity of images: in other words, the medium is the message.

Modern Moral Matters, the title of the Serpentine Gallery’s survey of Hamilton’s small body of “political” works, is named after Hogarth. But Hamilton’s intelligence is too coolly detached to be deployed as satire. And, more crucially, since all his images are mediated through news sources, often we just don’t know what to make of Hamilton’s position: is he simply making a strident political point or merely commenting on how the media uses and manipulates images? You may come to the conclusion that it’s got to be both, but still, there is often room for some uncomfortable ambivalence.

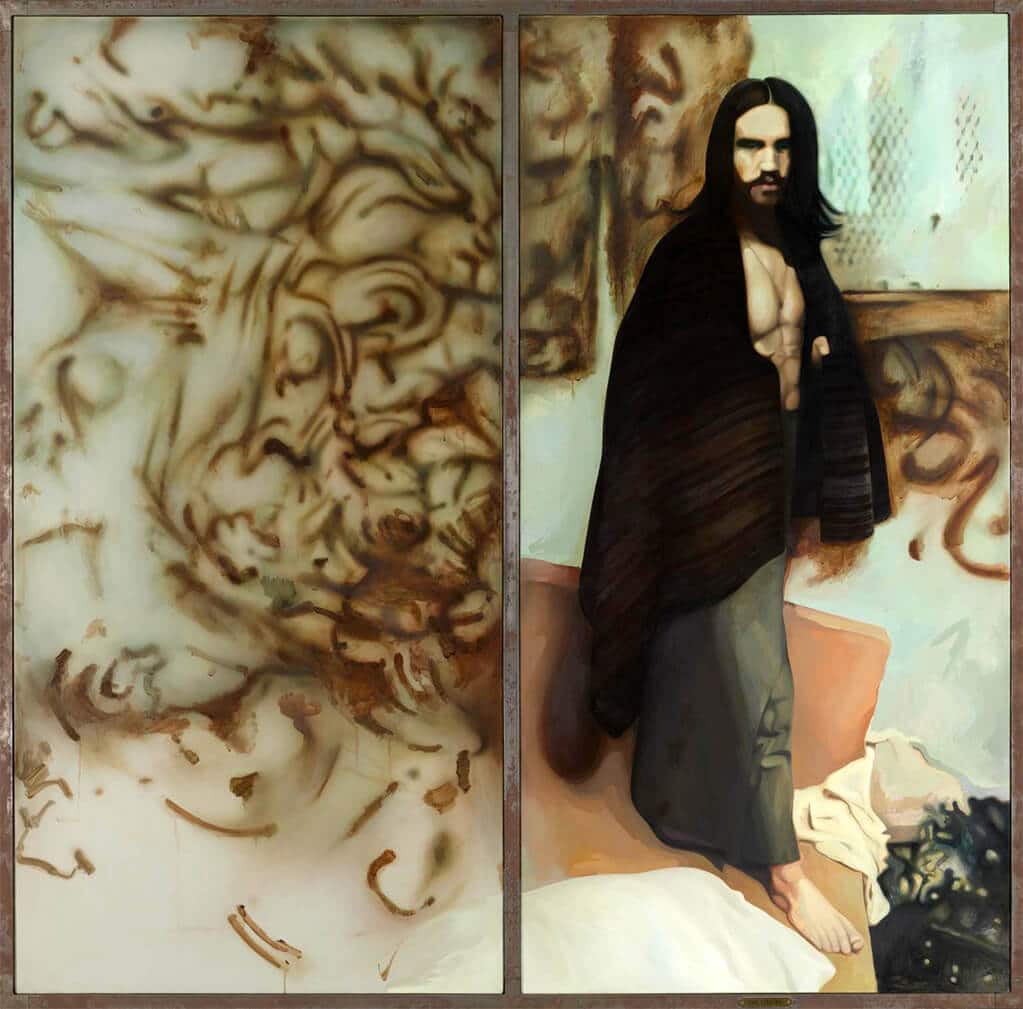

Take, for instance, his series of Northern Ireland paintings, the three large paintings, and their off-shoots, that come under the title of The Citizen (pictured), The Subject and The State. These were produced over the course of a decade, beginning with The Citizen, a painting of IRA prisoner Bobby Sands, which Hamilton began shortly after Sand’s hunger-strike induced death in the Maze Prison. This diptych features one canvas daubed with swirls of brown paint, which can be appreciated as a bit of abstract expressionism, but of course refers to the period of “dirty protest” in the early Eighties when IRA prisoners draped themselves in blankets instead of wearing prison clothes, refused to wash, and smeared their excrement on to the walls of their cells. The other side features Sands himself, looking messianic: bare-footed, blanket-shawled, long-haired and bearded – Christ, but crossed with Charles Manson.

So what can we understand of Hamilton’s position from this troubling image? Is Sands a political martyr or a dangerous terrorist? Sands’s status as a charismatic figurehead is upheld, but so is the moral ambivalance of the liberal left. And is Hamilton mocking the liberal left position or supporting it? Or perhaps the ambivalence is merely this viewer’s projection, and Hamilton’s position is rather more trenchant. After all, the marching Orangeman in The Subject and the young squaddie in The State are not individualised personae who hold our attention half as much as the messianic Sands.

A less disconcerting body of work, but one even more suggestive of their times, is a series of images that Hamilton made in the late Sixties following the arrest, for the possession of cannabis, of Mick Jagger and art dealer Robert Fraser. Swingeing London (pictured) shows the two men handcuffed to each other and attempting to cover their faces as they are led away in a police van. This image is repeated over several works, though, unlike Warhol, in different media. And there’s also a collage featuring cut-out newspaper stories of Jagger’s appearance in court, with each story dwelling at length on Jagger’s literal appearance: the print shirt, the colour of his tie, the cut of his trousers. The image is the story, but while Hamilton highlights just what’s wrong with this kind of vapid news coverage, he also unambivalently celebrates the power of the image.

There are two works which begin and end this exhibition which, rather than beguile with their clever shifting subtleties, as Hamilton’s best work can, irritate with their crassness. Treatment Room, 1983-84, features a sterile-looking room, complete with a bed and TV screen. The TV is placed above the bed, just like at the dentist‘s: Thatcher is addressing the viewer/ patient, but the sound is turned down. Among other things, Hamilton is again making a point about the power of the image over content – though this work contains an element of agit-prop that makes the work, rather than Thatcher’s brand of harsh medicine, hard to swallow.

Even worse is Shock and Awe, 2007-08, in which a gun-toting Tony Blair is dressed as a cowboy against an exploding backdrop. It’s a bit like Warhol’s Silver Elvis, though not half as appetising. In fact, it’s about as interesting, layered and subtle as reading a hundred protest placards bearing the word “Bliar”.