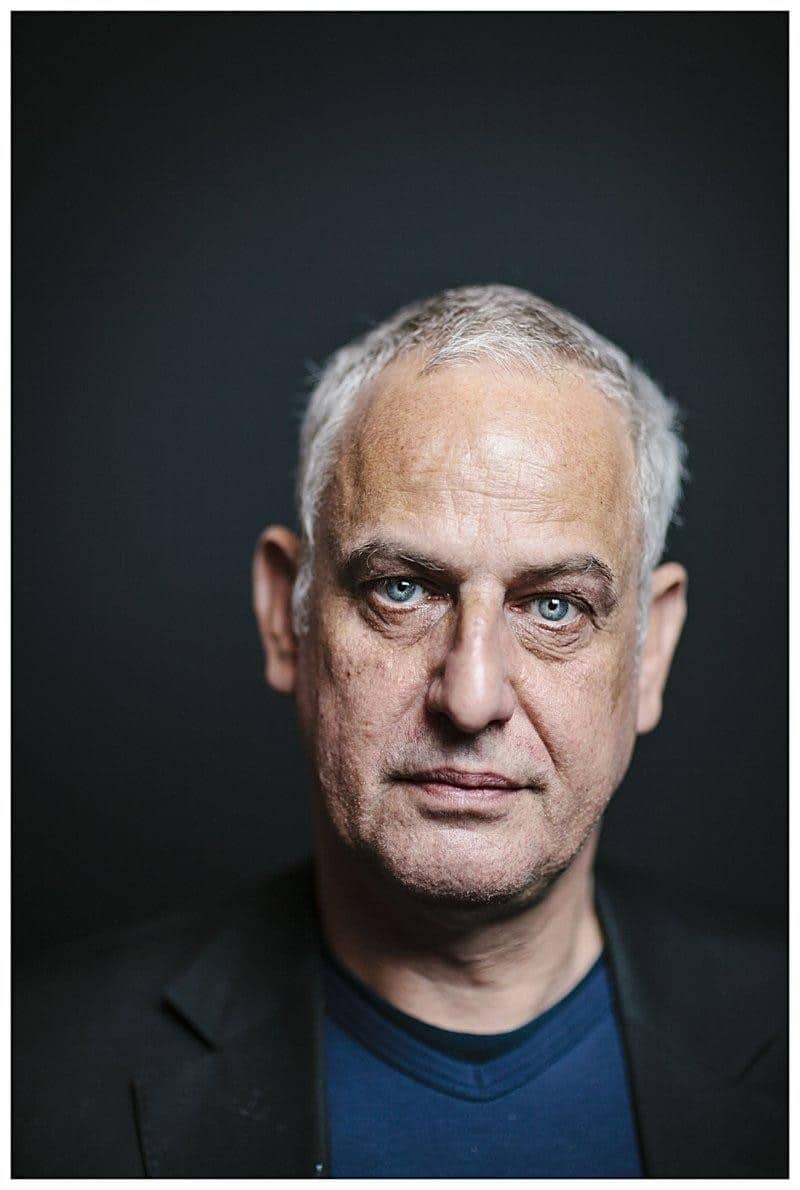

The influential Belgian artist currently has a display of his portraits, 'Glasses', at the National Portrait Gallery, while a major James Ensor exhibition he's curated opens at the Royal Academy

Belgian artist Luc Tuymans is one of the most influential painters working today. His subjects range from devastating historical events, such as the Holocaust or the politics of the Belgian Congo, to the inconsequential – wallpaper patterns, Christmas decorations, everyday objects.

A main body of his work is also portraits, usually of historical figures, or anonymous figures gleaned from photographs, often found in books such as medical textbooks.

His disquieting paintings are often strangely cropped and their surfaces pallid, as if they’ve been bleached-out. These are paintings that play on ideas of memory and history.

Tuymans is a also a prolific curator and in 2015 curated an exhibition of contemporary Belgian abstract art for Parasol Unit, London. His exhibition of the work of the Belgian painter James Ensor (1860-1949) at the Royal Academy opens later this month.

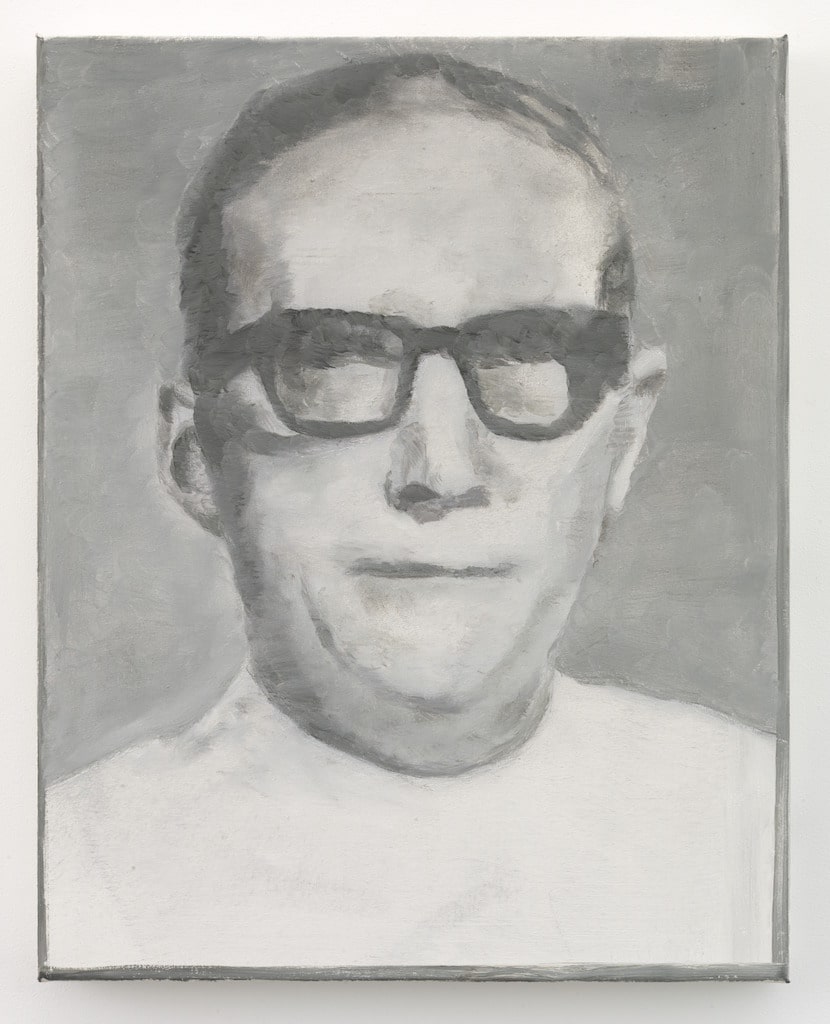

A display of his own portraits of people wearing glasses is currently on show at the National Portrait Gallery.

Tell us about ‘Glasses’ at the National Portrait Gallery.

It came about accidentally. In 2013, I was invited by the Menil Collection in Houston, Texas, to make a survey of 32 portraits, and to combine them with their collection. And I realised I had a lot of portraits with glasses and I hadn’t realised it and that to me was interesting. In the end, the director of the Collection didn’t want to do this but I kept the idea and I did a smaller version of it in Antwerp. And now it’s travelled to the National Portrait Gallery in a smaller version still.

It’s very small indeed. Just six paintings.

For me, it was really interesting to do just one space instead of spreading it over more spaces. It makes it more intense and I think more poignant. Less is more in a sense. And then, money-wise, the cost of transportation – these are also the things that limit you.

Do you usually work from photographs for your portraits?

Mostly I do. All the portraits in the display are from photographs, whereas their permanent collection is all made from life models. But we are now living in a different world and the portraits I’ve made are much more anonymous and distant and detached.

In the past you’ve talked about the struggle to maintain this psychological distance and detachment in your painting, and this made you abandon painting for some time. Tell us about that period.

I started as a painter, but I actually stopped painting in about 1980, because it became too existential, too tormenting, too suffocating. I thought there was no room, no real distance. And then by coincidence a friend of mine put a Super 8 camera in my hands, and so I started filming. And I concentrated on film for five years. From Super 8 I went to 16mm. In the end I was working with a 35mm camera and a crew and trying to make a film – a movie, not an art film.

Eventually, I went back to painting, and the filming informed the painting practice. The lens had actually given me enough distance to, in fact, come to better realise or conceptualise imagery from a distance. In that sense film practice and painting are very similar because they’re both about the approach to the image and not about the image ‘in the moment’, like you have in photography, which I’d be pretty bad at because I’d always be too late.

So what draws you to paint these ‘distancing’ faces so often?

Well, the idea of the space is the idea of the void, and the idea of the void is something intriguing to me. And if you see the show, especially one painting, you will see. That painting is called Diagnostic Portrait II. It shows you an image of a man out of a medical handbook called The Diagnostic View. What I did is crop the image in a specific way and sort of shifted the eyes, so that there is no empathy. You can’t relate to it as a spectator, because it’s just this hardened shell you’re looking at. There’s a complete denial of the idea of psychology, which makes it even harder to sort of grasp. Everything is treated with a certain cruel indifference.

Tell us about the Royal Academy’s James Ensor exhibition, which you’ve curated. He’s the artist famous for painting strange masked faces.

The beauty of the show is that it’s quite concise. We only went for high quality works. The Intrigue is the key work and it’s also the title of the show and it has the same intensity and element of danger as his most famous painting, The Entry of Christ into Brussels, which is a more grandiose, cinemascopic painting. The exhibition will give it a specific dynamic, which, in a large exhibition, you could not do in such a specific way. I’m not an art historian, I mean I studied art history but I’m an artist and I work from a visual understanding, so I’m not going to make an art-historical exhibition. It’s about creating another dynamic.

As a fellow Belgian you’ve always been intimate with Ensor’s work, haven’t you? Was he the first artist to really get under your skin?

Well, The Intrigue, the main painting in the show, is a painting I saw when I was 16 at the museum in Antwerp. As a kid, that had an appalling effect on me. Of course, he’s a very powerful painter – he knew what he was doing. On the far right side you will see antique masks out of Greece. You will also see a guy with a very strange hairdo, which is a reference to a specific judge in France. And then you have the more traditional folkloric masks. And in the middle you have the most intriguing person, who is the one with the top hat. He is the depiction of death and he is the only one, although his eyes are black holes, who peers right out into your face. Ensor painted it when he was 30 years old and it’s an ingenious painting – very powerful in its modernity, in its roughness, its brutality. At the same time it is a very refined painting.