An exhilarating exhibition following the curious arc of the Russian Modernist's career

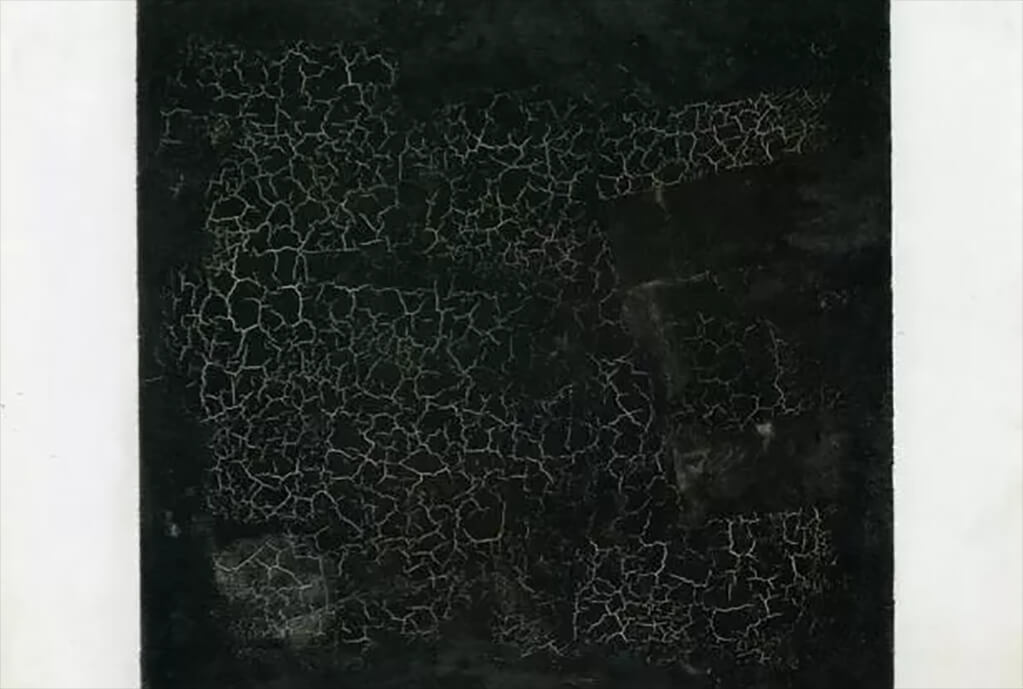

The year 1915 was a big one for Kazimir Malevich, as it was for the course of modern art. It was the year Black Square was first exhibited (June 1915 is the likeliest date of the painting’s execution, though Malevich himself dated it to 1913, insisting it derived from his designs for Futurist opera Victory Over the Sun). A simple black square on a white ground, it presented a gesture so bold, so audacious that it can only be rivalled by Duchamp’s Fountain of 1917. Just think of the all-black or all-white canvases by the likes of Ad Reinhardt or Robert Ryman some 40 and 50 years later and their minimalist radicalism diminishes when faced with Black Square and with Malevich’s startling white-on-white series three years later.

Black Square got its first outing in a group show of Russian avant-garde artists, The Last Exhibition of Futurist Painting 0.10, which took place in the newly named Petrograd. Just one photo, which is shown here, exists of that exhibition. We see two walls crammed with Malevich’s Suprematist paintings, a term, like Mondrian’s Neo-Plasticism, to denote an art that pursued “objective reality”, which is probably no more illuminating than the artists’ choice of neologism, but here to quote from source: “The artist can be a creator only when the forms in his picture have nothing in common with nature.” This could be a statement written by either artist, but it was written by Malevich in a booklet entitled From Cubism to Futurism to Suprematism, published in 1915 to outline his theories.

That 1915 exhibition is partially recreated from that small photograph, with nine of the 12 paintings whose whereabouts are known today. The original Black Square is too fragile to travel (in many of the paintings you see the black paint riddled with tiny cracks) and a 1923 version hangs high above the other canvases. It’s in the corner where the two walls meet and where traditionally religious icons were hung in Russian homes. Finding instead a painting of a black void must have given at least a mischievous thrill, if not the shock of encountering an act of blasphemy.

In the same room we find Red Square (Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions). The painting depicts neither a peasant woman nor, strictly speaking, a square, since two sides are slanted. I suspect Malevich of having a joke at the double duplicity (even despite the wonkiness evident in Black Square – his squares are often skewed).

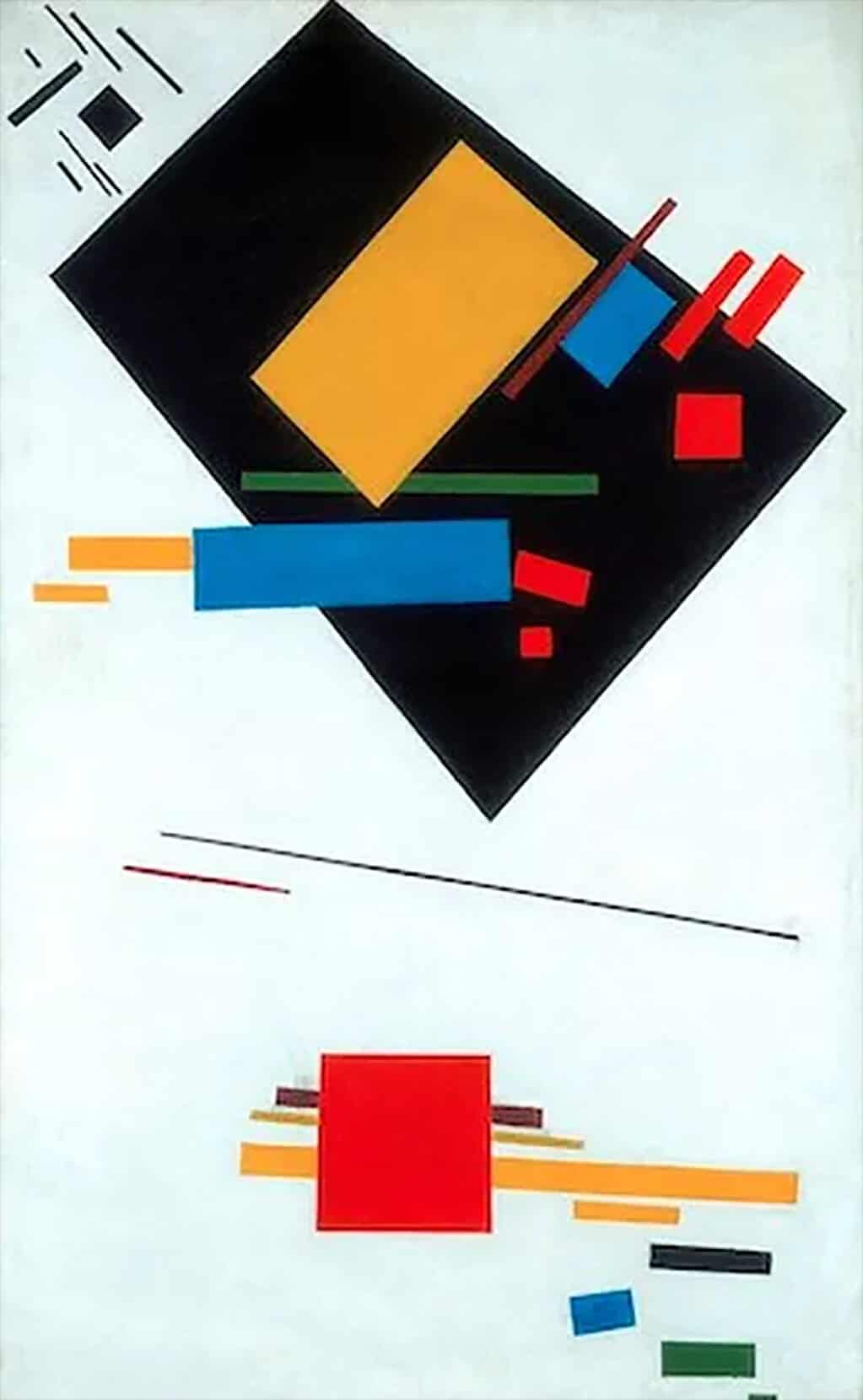

These small paintings, all from that year, are nearly all painted in single colours against a white ground. Most feature either a single or repeated form – a rectangle, a square, a circle – or intersecting shapes, such as a cross. The room exudes a calmness, a stillness, whose spell is broken in the next gallery. Here colours are multitudinous and exuberant. Dynamic floating forms – diagonal lines, rectangles, circles, the whole Euclidian army – overlap and intersect. This is what Kandinsky’s paintings begin to look like a whole decade later.

Malevich had tried all the French avant-garde isms for size – there’s an earlier room of Cubist paintings, naturally, but with a Russian twist – a samovar is hidden in intersecting Cubist planes, and a gallery of generic, heavy-set peasants traversing the land, with everything glowing in Fauvist colours. There’s also a big gallery featuring the charts and graphs he used as teaching aids, and if this is an attempt to blind you with science, it works. Move swiftly on.

Soon we’re under the shadow of Stalin. Malevich’s own revolutionary fervour is countered by the terror of the new regime. Its anti-avant-garde ethos prevails. In the early 1930s Malevich is arrested and interrogated and finally released. A final room is devoted to portraits, all painted in 1933: his mother, in a dour 19th-century Realist style; his young daughter painted in an unremarkable Impressionist manner. Then larger Renaissance-style portraits which are also a bit like figures on playing cards. One leaves this final room a little perturbed, or at least I did. He dies in 1935 and Black Square, along with most of his other paintings, is sequestered by the state, to remain unseen by the public for 50 years.

This is a superb, utterly fascinating exhibition which follows the curious arc of the artist’s whole career. Yet it’s undeniably Black Square that proves itself as the ultimate statement, the end-point, of Malevich’s artistic endeavours. He used a black square to sign those strange “Renaissance” portraits, and he dies, at the age of 56, with that groundbreaking painting hanging above his bed.