If L.S Lowry is an artist ripe for reassessment, then this exhibition could have gone a lot further

It’s part of the Lowry myth – the myth of many famous artists, in fact, whether or not it actually happens to be true – that he’s never been taken seriously as an artist by critics or by cognoscenti. Even the co-curator of this exhibition, T.J Clark says more or less the same. Lowry isn’t taken seriously, Clark has said, because anyone dealing with working-class life in class-ridden Britain can’t be taken seriously. Perhaps we might qualify this by adding that anyone dealing with working-class life from within it can’t be taken that seriously.

But should we take Lowry seriously? The title of this exhibition spells out why we must. It refers to the French 19th-century avant-garde mission of painting modern life, as Baudelaire exhorted artists to do and as Manet and the Impressionists single-mindedly did, weathering the brickbats of more conservative critics. And the exhibition itself includes paintings by Van Gogh, Pissarro and Utrillo – low-key paintings of suburbia and a metropolis untroubled, unlike Lowry’s paintings, by workers pouring out of factories. Next to some Lowry graphic works there’s even a drawing by Seurat, luminous and velvety, of an isolated figure in conté crayon. Whether these juxtapositions illuminate the English artist or merely flatter him may still be open to question, but he stands up well to the scrutiny.

Clark and his co-curator, and partner in life, Anne M Wagner, swiftly put to bed another myth – that Lowry was an untutored naïf, a Sunday Painter, unaware of developments on the continent. He may have been a “provincial” – though, like Howard Jacobson, one might take exception to the derision implied in that term, and wish to celebrate it – but throughout the Twenties and Thirties Lowry exhibited yearly at the Paris Salon, and in this he was at least more successful than Monet was in his early career, though Lowry himself remained largely uninterested in those light-suffused impressions of the fleeting moment by the French artist.

We also see a few canvases by Lowry’s tutor at the Municipal Art School in Manchester. Adolphe Valette’s dusky paintings of Manchester streets, with unseen chimneys belching smoke and electric lights exuding a dim, sulphurous glow are rather beautiful, and suffused with quiet mystery. Valette, too, instructed his evening-class student to paint what he saw of the world around him, though Lowry’s French instructor did not add the comic touches to his own paintings that Lowry found occasion to, especially as we see in his student’s more mature work.

In any case, does a painter disregarded and dismissed by the art establishment receive praise from critics such as Herbert Read and John Berger, both of whom are quoted at length in their regard for Lowry? And does the Manchester Guardian try to enlist them to the job of art critic? Lowry refused the offer, preferring to keep his day job as a rent collector, a job he kept till the day he retired on his 65th birthday, valuing the opportunities the job afforded him – the opportunity of seeing daily the things he painted obsessively.

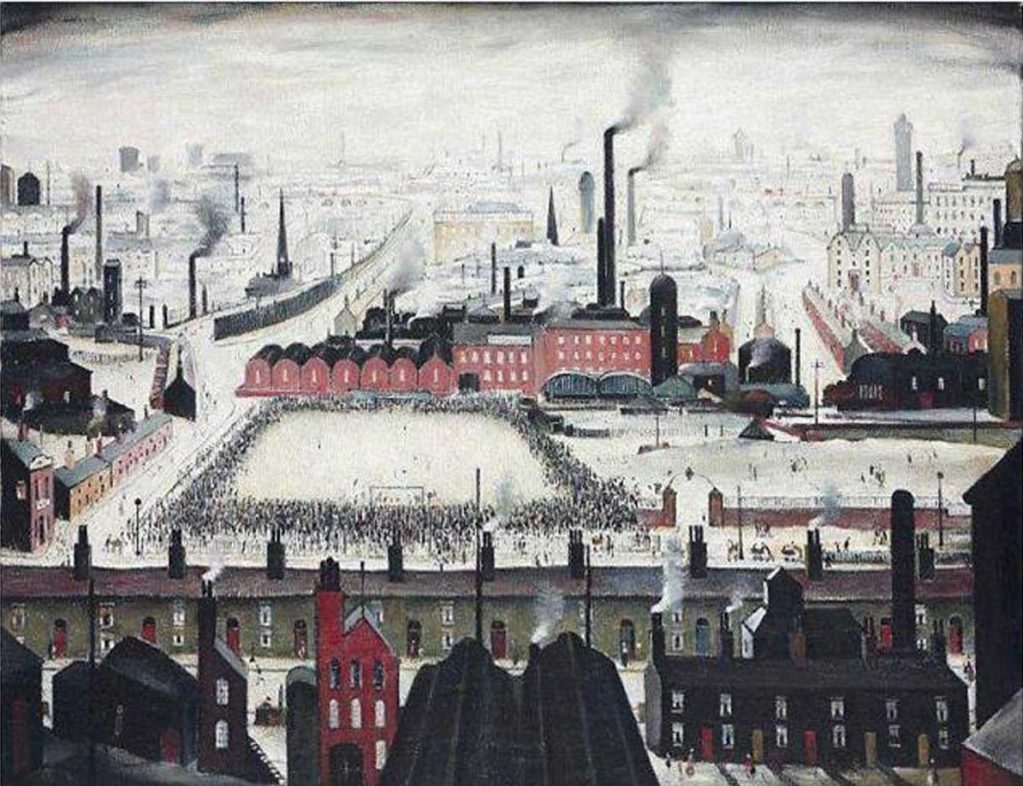

In the Twenties there were paintings like The Removal, 1928, in which we find a huddle of schematic figures, men with their cloth caps, women in their headscarves, gathered to watch an eviction. Though the title is elusive, it’s clear what is happening, with its meagre furnishings of a household lined up on the street and the solemn figures looking on. It’s a scene that was played out routinely on those streets. Similarly, Lowry is surprisingly coy in the title of another, earlier painting of 1926. An Accident, we are told, depicts a suicide. All we see is a tight huddle of bystanders contemplating the ghastly scene, as well as those who are drifting towards it, or those who, like the bystanders in Breugel’s The Fall of Icarus, have no idea what is going on and are simply carrying on as normal. They stand against stern rectangles of imposing factory buildings, with their industrial chimneys coughing out black smoke and with a foreboding sky on a low horizon. The panoramic scene with its slightly raised viewpoint keeps the viewer at a distance. Lowry was never a painter to invite the viewer in at too close a proximity.

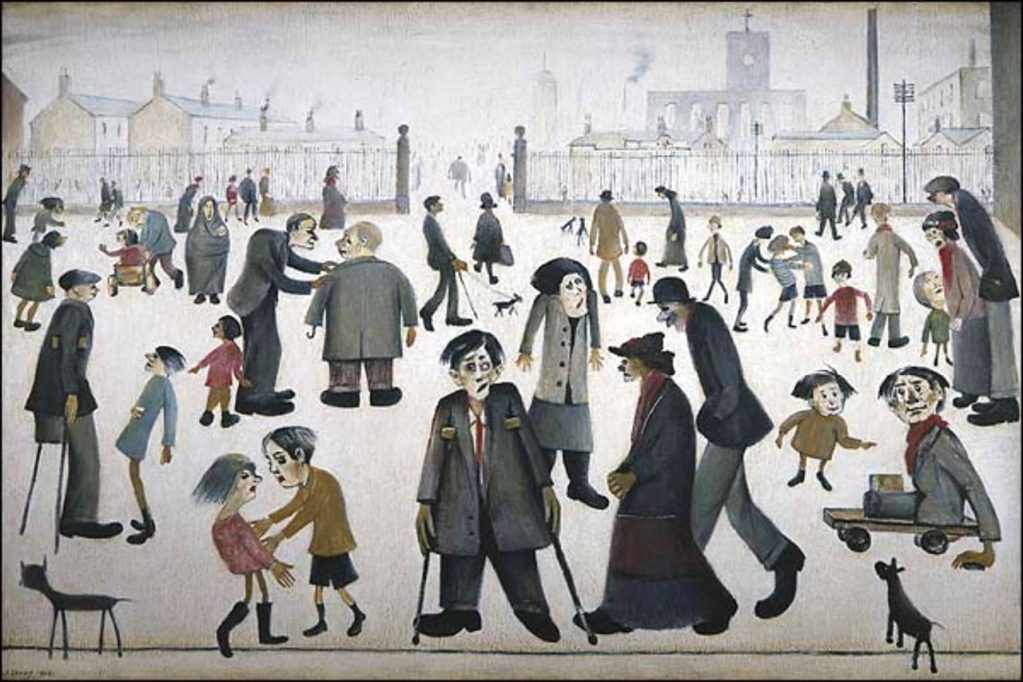

Often crude splashes of red – the red of a child’s jumper, a scarf or a detail of a building – brightens the blanket white of the ground and the monotonous greys and browns of his figures. Crowds huddle into themselves on their way to football matches, on the streets, or as they line out of factories, though sometimes they just stare forlornly back at us. Lowry’s paintings are austere, stark, poignant, even within the grotesque comedy of a painting such as The Cripples, 1949. Among the lame and the limbless and the haplessly gurning we see profiles that, alarmingly, are not quite human: brown dog snouts probe the bleak air – you can see them quite clearly. Whatever Lowry said about painting only what he saw is evidently not the whole story.

Later, large-scale, and very impressive panoramas show Welsh mining towns devoid of people, and there’s even a somewhat jaunty painting of Piccadilly Circus with its flashing Coca-Cola sign. But mostly it’s a sea of very similar industrial townscapes. The effect can be slightly deadening, a little monotonous. But the question of whether Lowry deserves to be taken seriously, the answer is yes. His paintings are deeply evocative, often very strange, though there’s a poignant strangeness to Lowry that is not fully explored here. He had a singular artistic vision, often edged with a sense of the absurd, that was true to the mood and temperament of the world around him, though, yes, his technical facility was limited. He was no Manet, this is true, but technical facility isn’t everything – and that is part of being modern, too. He was acutely responsive to the changing world around him.

Clark and Wagner have a thesis to promote, and that is that Lowry was a painter of modernity, which means the modern public space. And so this exhibition chooses to embrace only some of what Lowry had to say. What of those paintings suffused with a sense of loneliness so profound that one almost aches looking at them? Where is Man Lying on A Wall? Or his strange, very strange “family portraits”? If, at long last, Lowry is to be reassessed as a serious artist, then why not a full retrospective, where we can get the full measure of him? One misses those strange paintings of people – not portraits but expressions of states of mind. But for that you’ll have to take a trip to the Lowry Centre in Salford for their Unseen Lowry exhibition.