These days he may be best known through Lucian Freud's portrait of him, but Chichester's Pallant House hasn't forgotten the English painter, illustrator and sometime neo-romantic John Minton

John Minton, whose centenary is being celebrated at Pallant House, died 60 years ago, aged just 39. His name is often tagged at the end of the list of English neo-romantics: Paul Nash, Graham Sutherland, John Piper, and John Craxton, to name just four artists in diminishing order of fame and repute.

In fact, it is as a book illustrator rather than as a painter where Minton was at his most prolific and confident, and where he gained his most enduring success. And if his paintings are known at all today by those other than the most ardent observers of mid-twentieth century British art, it’s likely to be his lush Corsican and Caribbean landscapes and tableaux, with their vivid, hot colours and natural abundance, rather than his more whimsical English pastorals, his paintings of the Blitz, or his dour portraits of stiffly seated friends and lovers painted in stark London studios.

Indeed, we may actually know John Minton best of all through a painting that was painted not by him but by his friend Lucian Freud. A 1952 portrait by the younger artist is one of the first paintings in the exhibition. Minton’s glassy eyes are unfocused, lachrymose, and his thin, angular face wears an expression of doleful introspection. His greenish complexion makes him look rather sickly – or perhaps simply sick at heart – and his slack mouth reveals a prominent overbite. This small head and shoulders portrait is fluid but rather unflattering, as you might expect from Freud.

Minton painted a head and shoulders self-portrait a year later. In it he appears just as doleful, though there’s something more resolute in his gaze and in the set of his small, firm mouth. His hair is wilder, suggesting the self-flattering air of a young bohemian, while the portrait is cruder, painted with far less finesse and detail. We may get a sense of someone more self-assertive, but Minton’s painting lacks the psychological penetration of Freud’s portrait, and this appears less to do with the unexamined self than a lack of interest or even sensitivity in depicting the psychological hinterland of his subjects. His portraits of other people have a far greater concern with architectural space.

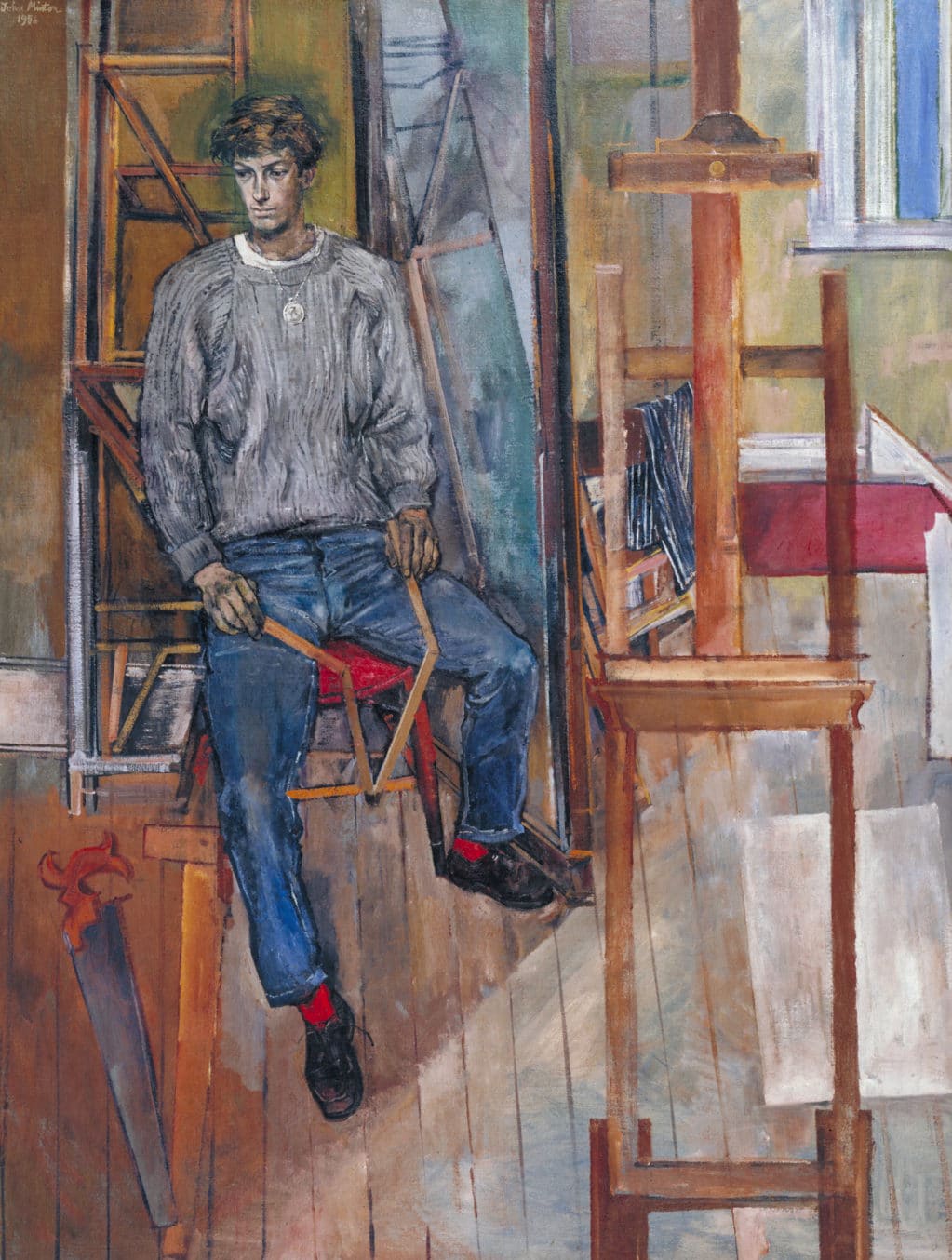

One senses, for instance, the influence of the spatially complex paintings and drawings of another excellent draughtsman, Alberto Giacometti, in Minton’s Portrait of Kevin Maybury, 1956. Maybury, a carpenter in the scenery department of the Royal Court Theatre in London, was the live-in lover he’d met while working as a set designer for two stage productions there.

Here Maybury’s eyes are downcast and his face slightly averted. His awkward, elongated form is settled on a small, rather precarious-looking chair. The wooden floor tilts forward, compressing the spatial depth of the room, and Maybury, fiddling with a collapsible ruler, is surrounded by the tools of his trade: a saw and a set square are by his right foot, while a step ladder leans against a wall behind him, just to his right; in front, to his left, is an easel, almost flat against the picture plane. Geometric forms dominate the painting and the effect is to distance the viewer from the sitter, who avoids our gaze.

It was Maybury who found Minton’s body after the artist committed suicide less than a year later, in January 1957, and on the easel, on this last occasion, was a large, unfinished and perplexing painting called Composition: The Death of James Dean. It’s in the last room of the exhibition and depicts a ghostly huddle of figures in a street filled with imposing buildings. The collapsed figure at the centre of the huddle resembles Christ during the deposition. Dean had been killed in a car crash 14 months earlier.

As with his portrait of Maybury, Minton’s figures seem often to appear at some remove from us, as if they’re little more than live props among a series of inanimate props. And what we glean clearly from his last, unfinished painting is how he used architectural setting as a kind of complex stage set to create a sense of tension or intrigue or mystery. We see the influence here of the unsettling paintings of the Metaphysical painter Giorgio de Chirico, who used imposing architecture to create a distorted sense of reality, or a dream reality. However, the sense of mystery was always there, certainly in Minton’s earlier wrought and heavily worked ink drawings of arcadian English landscapes that had earned him the label of neo-romantic. These heavily wooded landscapes, containing at least one male figure, owe their debt to Samuel Palmer, the so-called visionary painter of The Shoreham Ancients.

Minton was a heavy drinker, uneasy with his homosexuality during a time when it was still a crime and he experienced depressive episodes throughout his life. He’d been discharged from the army during the war after a breakdown (having unsuccessfully tried to avoid the war as a conscientious objector). But through all his difficulties, including the death of his brother in military combat a year after Minton had been discharged, he recovers enough to continue to draw and paint and design stage sets. And, for a time at least, there is even a sense of abundance and joy in much of his postwar work, especially since he had taken to travelling far and wide to sunnier climes, leaving the austerity of postwar Britain far behind.

His many book illustrations include the cover designs for the first editions of Elizabeth David’s extravagantly exotic cookbooks, A Book of Mediterranean Food, 1950, and French Country Cooking, 1951. In the first publication, tables teem with fresh produce, fish, lobster, oysters, French loaves and wine, in front of a panoramic view of the Mediterranean coast, while, in the second, a cosy French kitchen with flagstone flooring opens out to a view of a chateau. This is aspirational living taken to dizzying heights.

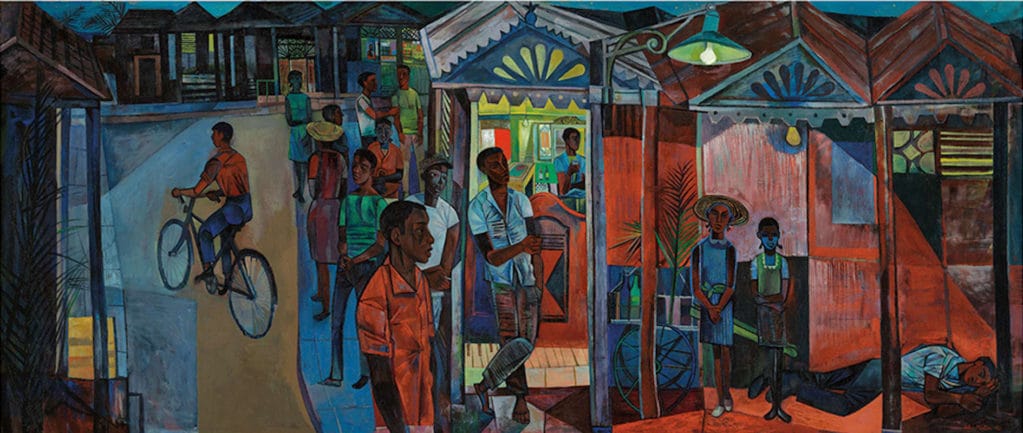

In the same year, Minton paints an ambitious painting of a night street scene in Jamaican Village, 1951. This five-foot long canvas shows villagers gathered around the wooden veranda of a bar starkly lit by electric bulbs. But instead of bustle, a sense of strangeness prevails, for there is something stilted and somnambulant about these largely non-interacting figures.

The exhibition shows an artist whose legacy is difficult to place, especially since he falters so soon after getting into his stride. One detects a crisis of confidence at so many stages, yet there is also something deeply satisfying about his simple yet vibrant still lifes and the beguiling coastal scenes that take us from Cornwall to Corsica and beyond.