Tate Liverpool's Portraying a Nation: Germany 1919-1933 draws together two artists of the Weimar Republic

The 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall was marked by an ambitious exhibition at the British Museum called Germany: Memories of a Nation. Through artefacts and art works spanning 600 years, we surveyed the slow march towards German nationhood. As history has shown, this proved a fragile entity. What was clear, however, was that the naming of a national assembly after Weimar, that centre of culture and enlightenment where Goethe had once presided in political high office, offered a promise of how a sense of nationhood might be projected onto the collective imagination after the humiliating defeat of the First World War.

But the Weimar Republic lasted only 14 years and it was a period immediately riven by hyperinflation, crippling levels of unemployment and political instability. And rather than memories of an enlightenment spirit guiding the new democratic state, what’s entered the popular imagination, through art, literature and film, is a far cry from enlightenment ideals. When we think of its capital, Berlin, we imagine instead a deliciously riotous decadence, which, though ugly and morally corrupt on one hand, proved a libertine’s paradise on the other. The tough interwar years yielded a hedonistic freedom for many, but it can now only be seen as a darkening prelude to what came after.

August Sander, The Painter Otto Dix and his Wife Martha, 1925/26, lent by Anthony d'Offay 2010 (ARTIST ROOMS)

Tate Liverpool’s superb exhibition, Portraying a Nation: Germany 1919-1933, focuses on the extended decade which saw the democratic failure of the Weimar Republic. But instead of presenting a survey of artefacts and various art works – we might, for instance, have seen examples of Dada or Bauhaus design to tell this story – we instead focus on just two artists of very different hue. One is the painter and printmaker Otto Dix, who appears, more than any other single artist, to encapsulate both the bourgeois and the demi-monde culture of the period, and the other is August Sander, the photographer who made it his life’s work to document an entire nation though his grand project People of the Twentieth Century. This Sander began in the early 20s and it occupied him for 40 years, remaining unfinished at his death in 1964.

The two exhibitions run in tandem, and there are more than 140 photographs presented in the Sander exhibition. Sander presents a taxonomy of class types, and his subjects are categorised and further sub-categorised by profession, trade or status as an ‘afflicted’ class (the blind, the mentally handicapped etc). There is a cool detachment in the undertaking – like the later Bechers’ typology of water towers – yet, in fact, character is often expressed in arresting and revealing ways. Shirtless and barefoot, and with a hint of androgyny in his masculine bearing, the Dada artist Raoul Hausmann strikes a dramatic pose as an avant-garde dancer, while writer and theatre critic Theodor Haerten looks anxious and intense in a tightfitting suit. With hands clasped nervously while staring intently at the camera, Haerten resembles a figure in an Egon Schiele painting and one’s impression is that this too is carefully and self-consciously posed to resemble an intellectual and creative archetype. In so many of the images there’s a defining sense of creative collaboration.

While Hausmann appears under the very loose category of The City / Types and Figures of the City, Haerten appears under the more specific The Artists / The Writer. Sometimes the same subject is cross-referenced. A nun, for instance appears in both The Woman (which gets its own category and there’s even a further sub-category of The Woman / The Elegant Woman) and Intellectual Occupations. Your sense of an exacting social science begins to break down under such idiosyncrasies.

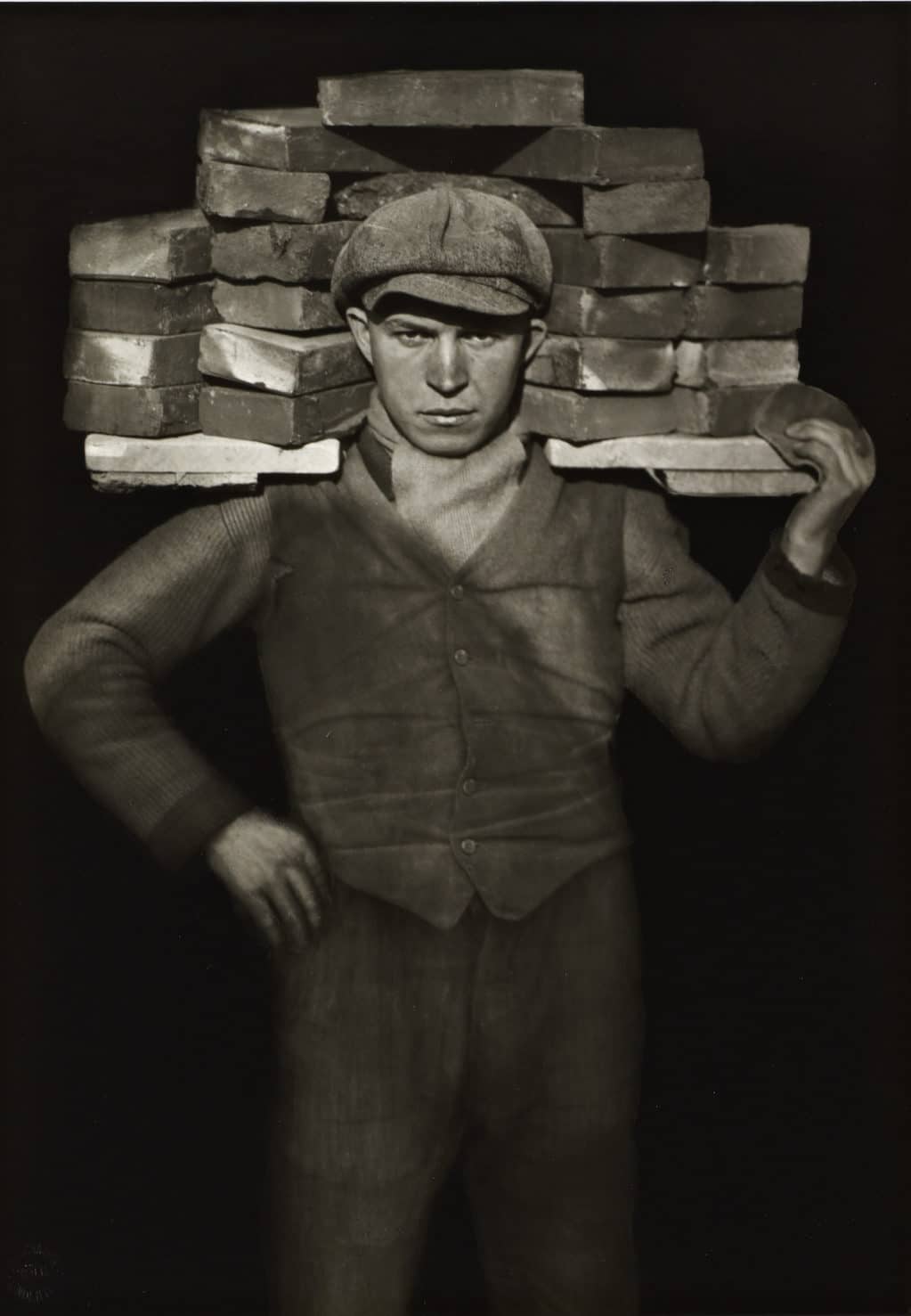

From the Turkish mousetrap pedlar to the young hod-carrier, who bears his considerable load with the strength and elegance of a circus strongman, we’re presented with portraits that denote class but also manage to speak of individuality. All of this, meanwhile, is supplemented by an initially incongruous amount of wall text offering a chronology of events leading up to the Nazi takeover of power. History unfolds with a cruel disregard for the humanity depicted, and if you’re not careful you can get lost in the text alone. I found myself compelled by both.

Vanitas (Youth and Old Age), 1932, by Otto Dix in Portraying a Nation: Germany 1919-1933 at Tate Liverpool

There are some 300 paintings, drawings and prints in the Dix exhibition: portraits of well-to-do men and women, femme fatales, prostitutes, murdered prostitutes, suicides, war widows forced to survive as prostitutes, brutish military men with prostitutes, scrawny, aged dominatrices wielding whips, violent street brawls and images of the war-afflicted. His satiric eye unifies them all, though his beautifully jewel-like watercolours possess a comic savagery that his larger paintings in oil and in tempera (he was fascinated by Northern European Renaissance portraits and strove to emulate them with technique and choice of materials) don’t. At least two paintings from the early 30s remind you weirdly of contemporary painter John Currin, most strikingly Vanitas (Youth and Old Age), 1932, with its kitsch, satirical take on the German Renaissance nude.

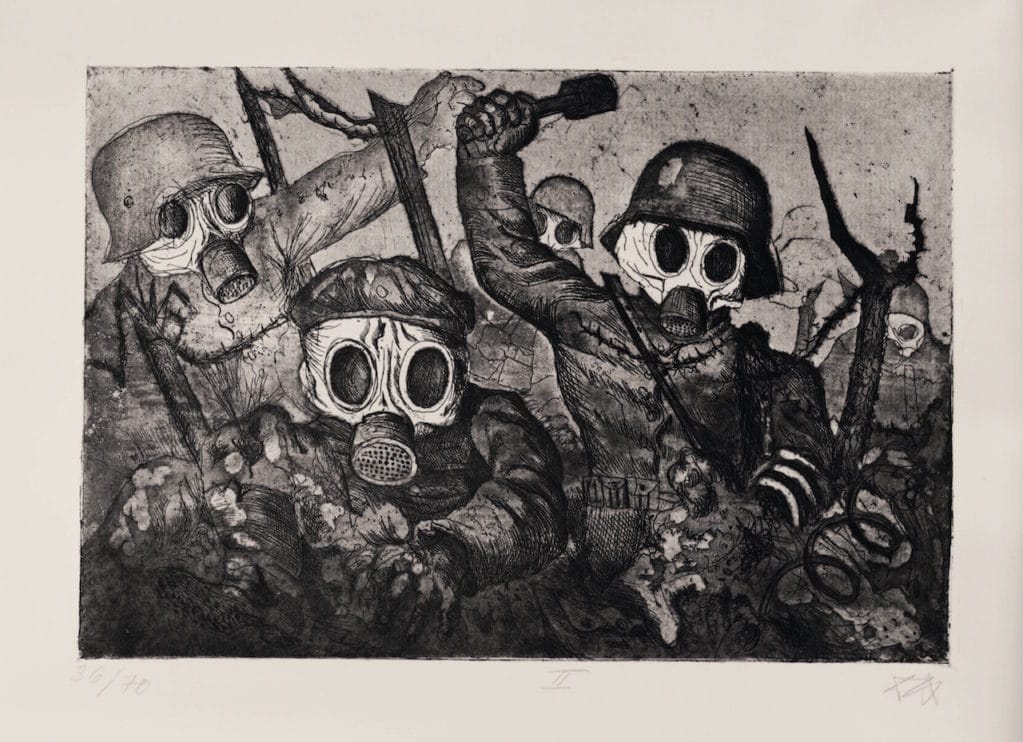

His devastating series of prints depicting the sodden, death-infested trenches of the First World War connect directly with Goya’s Disasters of War. Dix was a gunner at the Front in France, so these are deeply autobiographical works, though they were created several years after the end of the war. The crossing of medieval symbolism with acute realism plunges you into the immediacy of a waking nightmare. They are extraordinarily powerful works, and are among the several highlights of an extraordinarily powerful double exhibition.