A Swedish artist whose paintings were directed by spirit guides, and two artists who claim her as an inspiration.

Interest in artist-occultist Hilma af Klint has been growing steadily since her paintings had their very first public outing in 1986, 42 years after her death. The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, featured 16 of her paintings; and she couldn’t have received a more auspicious introduction. Displayed alongside the three indisputable giants in the evolution of pure abstract painting, Kandinsky, Mondrian and Malevich, a case was made for her inclusion in the modernist pantheon.

Yet the show’s primary purpose wasn’t to bring into the art historical canon women artists who’d been long and unjustly neglected, but to re-establish abstract art’s beginnings in arcane mysticism, reconnecting it with Theosophy and associated esoteric movements that had come in its wake, which in turn had their deep roots in the 19th century obsession, among intellectual circles as much as those outside them, with the occult and mesmerism and for holding séances in aunt Nellie’s kitchen – the whole mystic rag-bag in effect. It’s hardly surprising that we now downplay or overlook all this in favour of pure formalism.

To this effect, af Klint’s status as an artist who predated Kandinsky as “the first purely abstract painter,” has been often repeated, but that is to precisely downplay the thing that drove her art – that she saw herself as the conduit for a bunch of spirit guides who instructed her to paint “on the astral plane”. Modernist artists embraced the teachings of the charismatic Madame Blavatsky to a point – though they were resolutely masters of their own creations (the catalogue gets a little snipey at their “self-publicising” huge male egos) – but af Klint’s art was of a different order. And though she’d trained as an artist, she pursued her calling in isolation, away from avant-garde circles.

None of this in itself should diminish her artistic innovations – artists believe all sorts of things, and if she believed spirit masters directed her work, it’s up to us to decide whether we find that an interesting enough entry point into it, though I suspect many of us simply won’t.

This latest survey of her work, at the Serpentine Gallery, is the Swedish artist’s second in the UK, the first being a smaller display at the Camden Arts Centre in 2006 in which she was paired, somewhat improbably, with German assemblage artist Isa Genzken. So what to make of the paintings? Is the world ready for work that Rudolf Steiner, whom af Klint had met briefly in 1908, had told her would neither be accepted nor understood for another 50 years, and must therefore be kept hidden from the public gaze? Though apparently devastated by her mentor’s words, she herself later stipulated that her work must not be be shown until 20 years after her death.

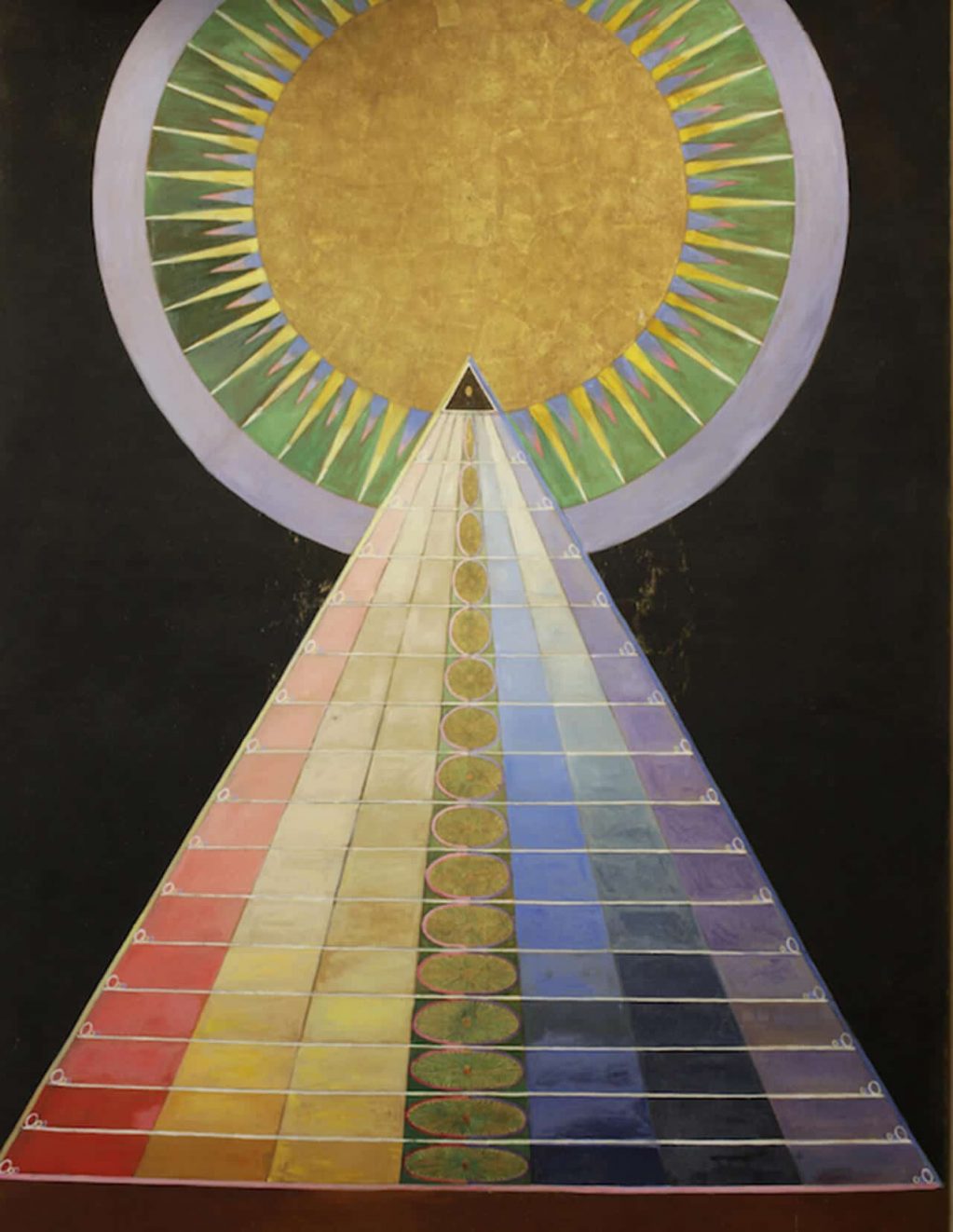

Well, what you’ll find is a stylistic mixed bag. Geometric shapes and loops and soaring parallel lines and circles and spirals and stylised flowers and birds and brawny humans – pairings of male and female – in symmetrical unity. Occasionally, you’ll find Christian iconography – a cross or a dove. Swans, usually a black one and a white one in a tangled embrace, or perhaps a stylised arrangement of black and white swans, feature, too.

The first group of works, in a series called Altarpieces, would look great in a Masonic lodge. I think of KKK Grand Wizardry – unfair, I know, but that’s what goes through my head (the title of her major series, ‘Paintings for the Temple,’ might suggest a warning). In short, I greatly dislike these paintings. The kitschiness of the figurative ones is just awful. But it’s not just the motifs. These paintings seem flat to me, flat and stodgy and inert and often not very well painted – she should have had a word with those master spirit guides. They look a lot better in reproduction, the colours more crystalline, less muddy. The tiny, often freer watercolour paintings are, however, mostly rather lovely. By contrast, these actually don’t reproduce at all well – good painting rarely does.

It hurts not to love these paintings. You like the idea of them: the monastic dedication to one’s art, the disappointments and setbacks endured, the female toughness that rose to the challenge, moves you. Perhaps the selection is partly the problem – she painted at a prodigious rate, so she produced a lot and one can feel exactly the same about an awful lot of Kandinsky. But on the basis of this display I’m really not keen to see more.

Stroll over to the nearby Sackler Serpentine and you’ll see two artists inspired by af Klint who will, I hope, excite you no end. Kerstin Brätsch and Adele Röder are two artists in their thirties who work collaboratively as Das Institut, and who also invite other artists to collaborate with them. Don’t let the presumably tongue-in-cheek name put you off – this exhibition is fun, beguiling, exquisite. There are paintings on huge glass plates or transparent mylar sheets with imagery inspired by ancient life forms, fossils, crystals, German Expressionism, neo-expressionism and early photograms. One long wall is hung with body prints of the artists – I assume they’re the artists – in dynamic poses, doing shadow dances. I loved this exhibition. It’s visually rich and tantalising and beautifully installed.