An irrepressible joy touched by pathos in the French modernist's late works.

When it comes to the two vying giants of 20th century art we do – don’t we? – all fall into that cliché of two opposing camps. You have the seductions of colour and decorative form on the one hand and you have the more classical rigours of line on the other, the one exemplified by Matisse, the other by Picasso. It’s not an absolute demarcation – a line that’s never blurred (and Matisse had, of course, a very elegant line); just a profound difference in emphasis and sensibility. It’s also a difference in artistic temperament. And how we respond shows, I think, a difference in temperament, too.

Me? I’ve always gone for the head, not the eye, or indeed the heart. In other words, I’m in the Picasso camp. And when it comes to the late works of either artist, I’ve always found myself in sympathy with the old-age rage of Picasso. And not just with the fury, but the fear. Picasso, he was complicated. And it’s all there in his work.

The dichotomy of the head and the eye may also explain why it’s hard to love, rather than to simply admire, Picasso, and why it’s so easy to fall head over heels for Matisse. When something expresses itself with such an irrepressible joie de vivre, you fall in love with it. You can’t help yourself; it’s intoxicating. But there’s got to be something else there too. A chink where sadness and vulnerability creep in and make their shadowy presence felt, or else all that joy would be insufferable. There’s poignancy in Matisse’s late works, in those exquisite cut-outs that occupied him so intensely in the remaining decade of his life and to which this exhibition is devoted, and it makes the joy even sweeter. As in life, so in art.

Just look at the “maquettes” for Jazz, the paper cut-outs made during the war and finally published in book form by the important art publisher Tériade (who also came up with the title for this collection of falling and dancing figures) in 1947. By that time Matisse had been living in Vence for four years, having fled there from Nice to escape the bombing in 1943. He was already very ill and infirm and Jazz was the fullest expression to date of his simple cut-out technique, developed – though for years used as a tool to compose his paintings – because he could no longer hold a brush effectively.

Under his close supervision assistants painted the paper in bold, bright colours using gouache to which he, with surprising dexterity, applied a pair of scissors – hence “drawing with scissors”, though as the term “maquette” suggests, the cutting is perhaps closer to sculpting, since you’re also physically taking away as well as following a line. With that, the forms were then pinned to a surface, often in a process of constant revision, before finally being laid down with glue, or simply left as they were in his studio (film footage allows us to watch this process in action).

Here, a number of the original Jazz cut-outs are shown with their printed versions lined in glass cases in one long gallery, and what’s immediately evident is how much the printed versions have lost in translation, their vivacity leached by the mechanical process. Colours are flattened, while forms have lost their layered rough-edgedness. Their “sensitivity” has been forfeited, as Matisse observed. I can’t overestimate what a pleasure it is to see these in the raw: here we find Icarus (pictured), a figure white against black as if an irradiated imprint in the cosmic darkness, with jagged red “flames” bursting through his chest. The jagged heart-burst is echoed in the forms of fiery yellow stars against a calm midnight blue.

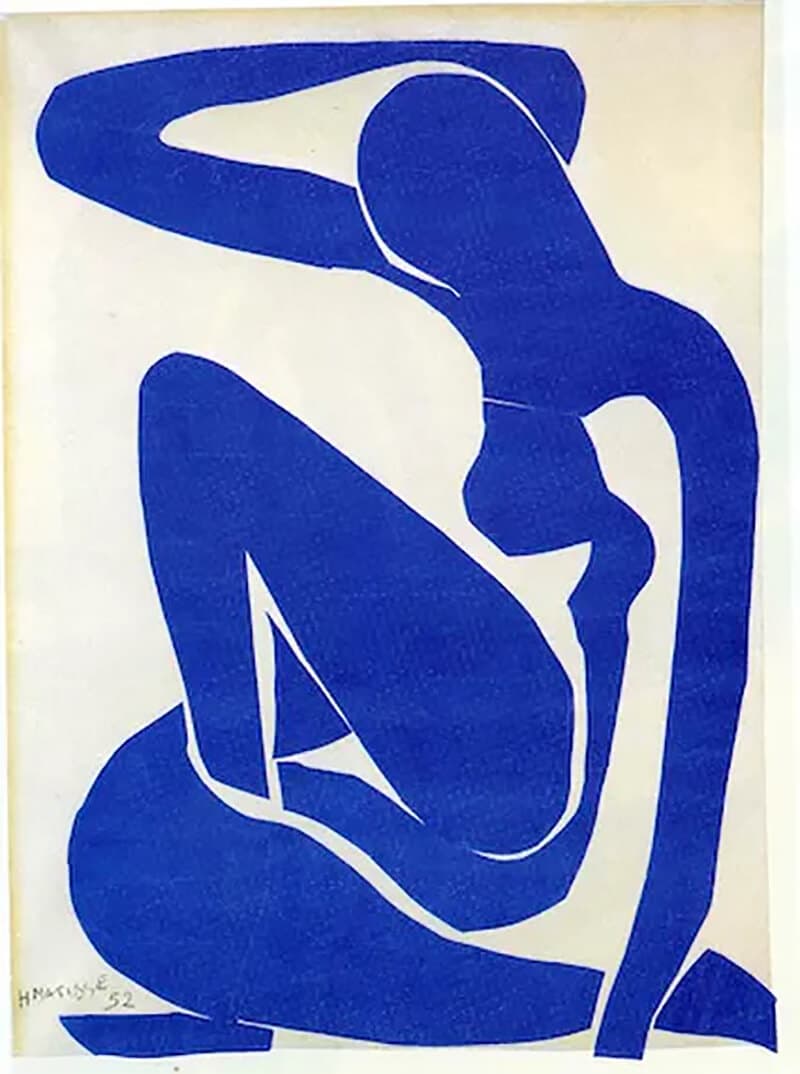

Falling, tumbling figures crop up again up in a series of cut-outs made for the cover of a magazine called Verve, again published by Tériade (pictured). For me, these are among the most affecting works here. They are full of pathos, but as far from wiltingly sentimental as you can get. Their heat, their energy contrasts with the elegant and formidable Blue Nudes.

The hang is beautiful. In one room we find an arresting “salon-hang” of smaller cut-outs, while larger works, with their “bleached-white” silhouettes against greys, burst with marine life. As one progresses, the bigger the works, often the more decorative the scheme, and I’m afraid I’m always left cold by his designs for the Chapel of the Rosary at Vence. A room is dedicated to both the discarded and the final cut-out designs for this tiny church in south-east France, including the work for its stained-glass windows. For me, the show ends with an overly decorative whimper, with another stained-glass design, this time for the Time-Life Building in New York.

But before we get there, we’ve already arrived at the final simplicity of the Tate’s own The Snail, 1953, made a year before the artist’s death and shown with its sister compositions, Memory of Oceania (MoMA, New York) and Large Composition with Masks (National Gallery of Art, Washington), all originally conceived as one unified work. Just how long did it take him to determine The Snail’s final form? You wouldn’t want to rearrange a thing. It’s perfect.