The Finnish artist's dramatic self-portraits tell us about her relationship with grief and isolation

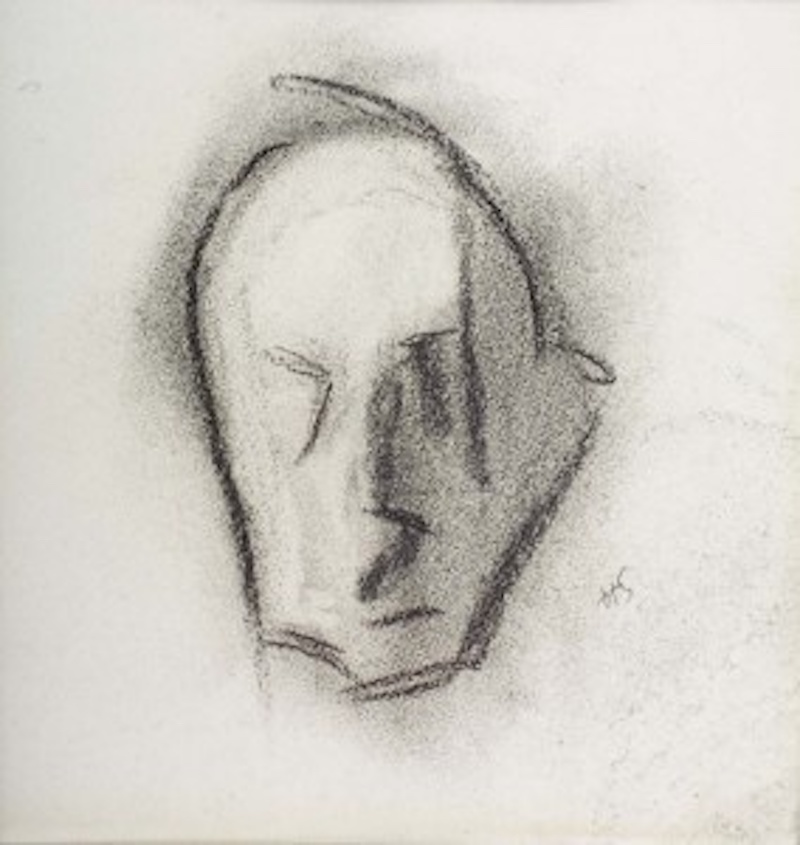

It could be a death mask, this fleshless head with hollowed-out eyes. Just a few broken lines in soft charcoal, the disembodied face tilts slightly forward, suspended in space. There is no looking, no self-scrutiny, nor an awareness of being the object of another’s gaze. With head and features pared down to this fragile husk, it’s an incredibly raw portrayal of human ruin; an abject image of renunciation. Whatever was once inside that inscrutable head isn’t accessible to us.

Drawn in 1945, shortly before the artist died aged 83 in the January of the following year, this was the last self-portrait Helene Schjerfbeck drew or painted. In an exhibition that will bring Schjerfbeck’s work to UK audiences for the first time, this tiny drawing is displayed near an equally tiny portrait which the Finnish artist drew when she was in her late teens or very early 20s.

In this early self-portrait, Schjerfbeck regards us with a clear-eyed intensity; her self-possession evident. She appears to be looking at the viewer with a slightly questioning gaze, though the viewer in this assured display of self-scrutiny is, of course, herself. But what is also clear is that she sees herself as the object of another’s gaze, and meets it with steely confidence.

A world and a lifetime apart, these two drawings can currently be seen at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Schjerfbeck had a long, prolific life, and though this exhibition takes a close look at the range of her output, it’s her self-portraits that appear so thoroughly modern in a very unnerving way. She painted them throughout her life, but particularly so in her final two years, as she found herself increasingly isolated with old age and ill health. The central gallery in the Royal Academy is given over entirely to a chronological selection of self-portraits.

“My idea from the start was to have the self-portraits as part of the exhibition,” says James Lewison, who curated the exhibition. “I think all of Scherfjbeck’s work comes out of self-portraiture,” he continues. “If you look at the later portraits [of other sitters], they’re not really psychological portraits. The sitters never look at you, the viewer, or Schjerfbeck, the artist. It’s hard to penetrate inside them. There’s this engagement with masking – with make-up, with fashion, and we see that in Schjerfbeck’s later self-portraits – which comes out in ways that are quite unique.”

The Helene Schjerfbeck exhibition features more than 60 works, and besides self-portraits, there are still lifes, quiet interiors and portraits of models, family members and friends – all in a soft, muted, and very Nordic palette. A portrait of the artist’s mother in an extended side-view Whistler-esque pose stands out, and there’s a strange, oddly sinuous portrait of a one-time lover, who left a devastating sense of betrayal when he broke off their relationship.

The survey offers a compelling insight into the creative trajectory of an artist who began her prolific career painting in the style of French salon realism, showed something of the influence of the Dutch masters, and later fully embraced the coolly precise and harmoniously restrained frescos of Italian Renaissance artists such as Piero della Francesca, right down to scraping back layers of paint to affect the aesthetics of weathering and age. On request, she even made copious copies of the paintings of Old Masters, including Holbein and Velásquez, to furnish collections back home that lacked such treasures and which could be used as teaching aids.

A modernist in a thoroughly Nordic sense, Schjerfbeck absorbs the looser brushwork of Impressionism, the disquieting moods of Symbolism, and the severe paring down and near-abstraction that connects her to the Parisian avant-garde as she fully emerges into the 20th Century, but she never abandons traditional subject matter. This is in common with so many of her Nordic peers – including Edvard Munch, with whom (in terms of her self-portraits at least) she has been compared.

Meanwhile, some of her portraits bear a passing resemblance to those of Modigliani, though she’s far from imitative. She seems to have found her feet fairly quickly as an artist, studying in Paris, travelling to Italy, and briefly, on at least two occasions painting in St Ives, Cornwall.

Ironically, it was in St Ives where she produced what became her most celebrated work, still her best known today. In 1888 she painted The Convalescent, depicting a child with bright eyes, feverish complexion and delightfully tousled hair. Swaddled in white sheets and perched on the edge of a huge weave chair, the child clasps a single spindly flower stem placed in a cup. It’s an image of hope, of fragility but resilience. It’s a slightly sentimental painting which has much in common with genre paintings of rosy-cheeked children of which the Victorians were so fond. And as for Munch comparisons here, the painting couldn’t be further from the Norwegian artist’s The Sick Child, painted just three years earlier.

But in much the same way as Munch is celebrated in Norway, Schjerfbeck is Finland’s very own national artist, though, until recently, she’s hardly been known outside the Nordic nations. She was a native speaker of Swedish, which is still an official language of Finland, and early on her work was bought by both private collectors and public collections in Sweden.

But it’s at Helsinki’s Ateneum, part of Finland’s national art museum, that most of her paintings can been seen. Successful in her own lifetime, she was the only woman artist who sat on the board of the Finnish Art Society. However, she didn’t have her first solo exhibition until 1917, when she was in her 50s, and she wasn’t a household name in Finland until the 1980s, when feminist art historians sought to rescue under-recognised female artists.

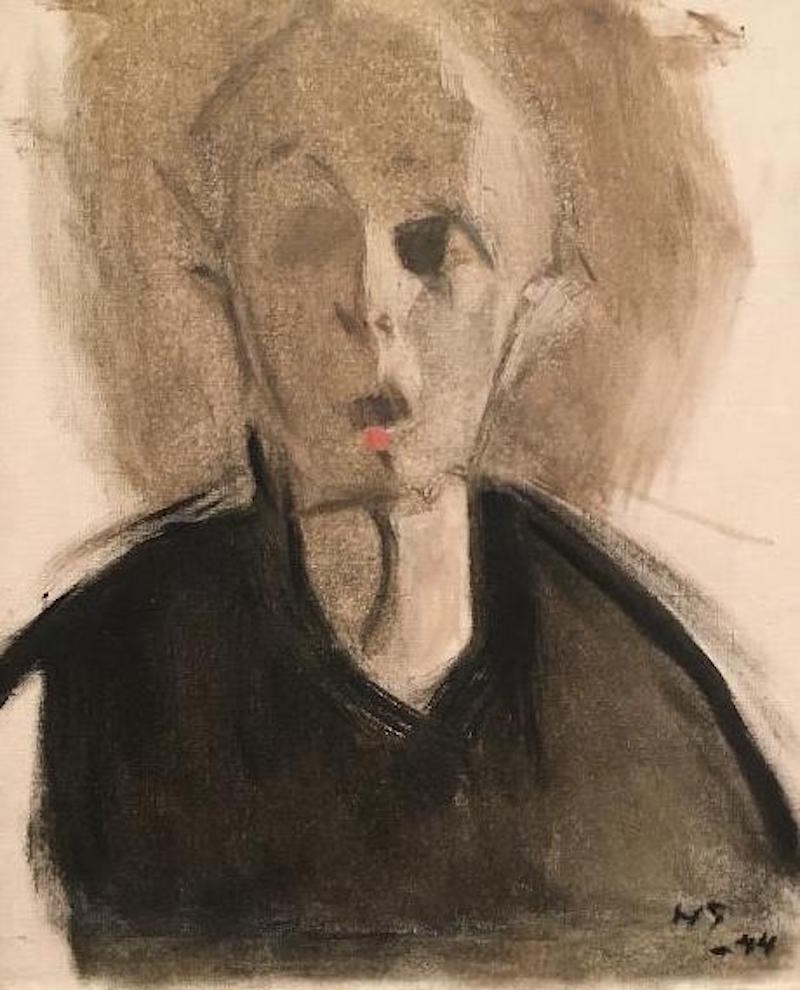

“What we know she was looking for is that essence of life, and in painting it,” chief curator at the Ateneum Art Museum, Anna-Maria von Bondsdorff, says. “So, in a way, you can look at these self-portraits and see how they capture an essence of life. If you look at that one [Self-Portrait with Red Spot, 1944] it has a very small dot coming from her mouth – she is vanishing, but there is still the red dot.”

Lewison argues, convincingly, that Schjerfbeck’s work comes from a sense of grief. “I think there’s a strong sense of [it] in her work,” he says. “And although she wasn’t completely isolated, I think she had a feeling of isolation, and I think it was this grief that led her to cut herself off.

“She had this disastrous break-off and engagement… she had to look after her mother, and then her mother died. She lost her father very young, and she had this physical incapacity as a result of an accident as a young child. I think,” Lewison adds, “that all these things came into the mix.”