Seductive and profoundly moving: a survey of the once celebrated neo-Romantic artist Graham Sutherland

Graham Sutherland and George Shaw have two things in common. They are both painters and both are associated with Coventry: Sutherland made his famous altarpiece work – a tapestry – for the city’s rebuilt cathedral, while Shaw grew up in Coventry’s Tile Hill, a housing estate that’s become familiar to us through Shaw’s beautiful and melancholy Humbrol enamel oil paintings.

But other than these tenuous connections, you may find little common ground between the pair. Sutherland’s imagery reaches back to the 19th-century Romantic tradition through painters such as Samuel Palmer, whilst his acid-bright colours and contorted forms are heavily indebted to Picasso and to European Surrealism. Shaw’s paintings, on the other hand, are avowedly realist, meticulously transcribing the forms represented in photographs he’s taken of every nook and cranny of his childhood estate. His palette, too, is limited to those largely dull, khaki hues of Airfix models.

But for all their formal differences one can see the connections and resonances of a shared vision wedded to an English sensibility. A commitment to the landscape and the genius loci underscored Sutherland’s searing, apocalyptic vision, whilst Shaw’s sensitivity to the fragile, desolate beauty of the world of his childhood – the world of shabby, humdrum, utilitarian modernity – is what infuses this contemporary artist’s work with something rather achingly Larkineque.

Shaw, the Turner Prize nominee who won the popular if not the judge’s vote this year, curates Graham Sutherland: An Unfinished World, a beguiling and utterly seductive exhibition of the artist once nationally celebrated but for decades rather neglected, with no major retrospective show in recent decades. He was, along with the older Paul Nash, part of the English neo-Romantic movement of the inter-war and postwar years, but his considerable reputation steadily declined, and, by the time of his death in 1980, aged 77, he was seen to be not quite Nash’s equal.

This may be because, as strange and as unsettlingly as his paintings are, they rarely possess that mysterious and startling anthropomorphism that animate Nash’s work. By comparison Sutherland’s finished landscapes can often feel a little stilted, rarely anything like his keenly alive, acutely perceptive portraits, a genre at which he excelled.

This survey focuses instead on Sutherland’s works on paper, those studies and sketches which possess a quickness and fluidity that his finished paintings often lack. The exhibition concentrates on three aspects of Sutherland’s career: his Welsh landscapes from the 1930s; those depicting the bomb devastation on the Home Front; and the works created after his return to Pembrokeshire in the 1970s, a trip that was made to film an Italian television documentary about his work but which saw him remain for two years, having lived in France from the late Fifties.

Sutherland was exhilarated by the ‘exultant strangeness’ of the Pembrokeshire landscape, but the natural forms he painted are fuelled just as much by his imagination. This appears as distinctly dark ruminations of the soul, a devastating vision that appears just as apocalyptic before the war as it does during it or in its immediate aftermath. A Catholic convert in his twenties, he’d experienced the tragedy of losing a severely disabled child in the early years of his marriage (it’s somewhat shrouded in mystery but there may have also been a stillbirth, after which he and his wife remained childless, and the couple would refer to his work as ‘their children’).

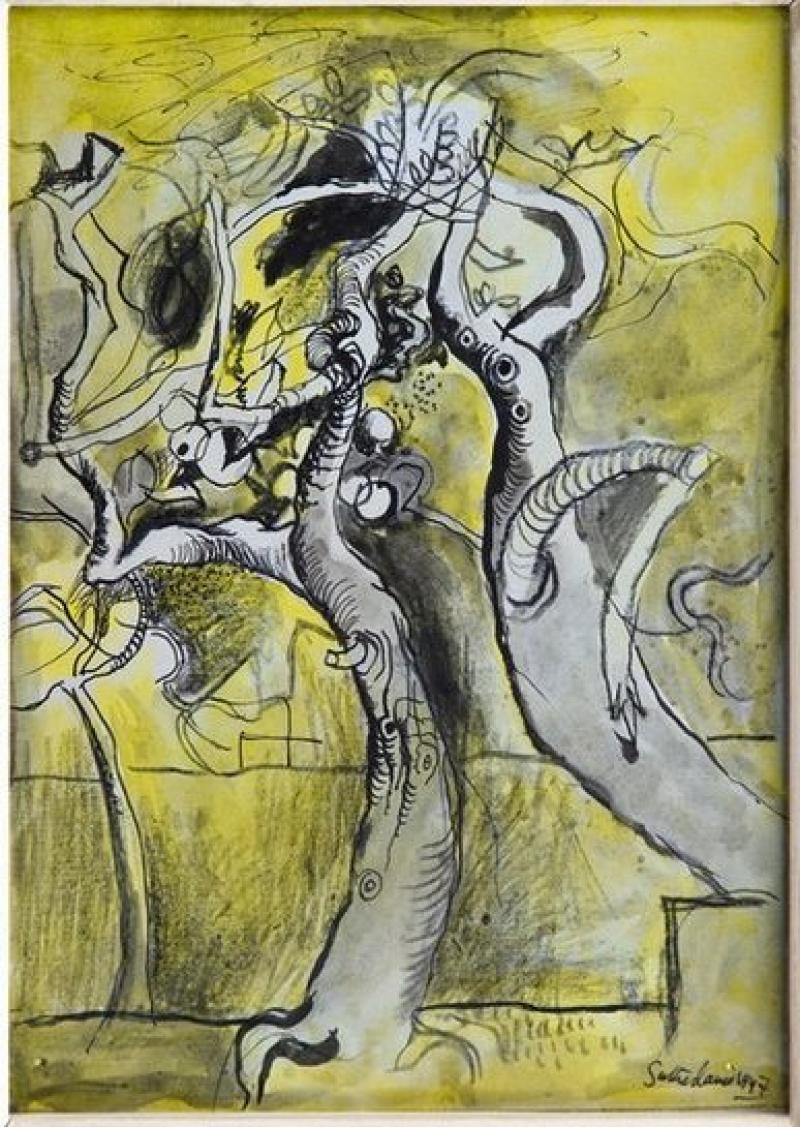

Two Trees, 1947, shows the spiky embrace of two twisting and extruded trees against a scorching yellow background, whilst Welsh Landscape with Yellow Lanes, 1939-40, features rearing, sulphur-yellow country lanes which the sun, coming out from behind an ominous mass of inky blackness, appears to be aggressively attacking with its rays. In the bottom left the picture features another inky black smudge, which looks a bit like a Rorschach but perhaps more – with its suggestion of withered or truncated limbs and seeping trails of bodily effluence – like an embryonic figure from a Bacon painting.

It’s Bacon who again comes to mind – his powerful George Dyer paintings – in the only picture in the exhibition to feature a figure. Man & Fields, 1944, is a strange picture of a profile of a man, his face flat against the foreground and wearing a haunted, harrowed expression. Behind him a sickly yellow and pink landscape would appear to offer no respite to his condition. The image is an arresting curiosity amid a large body of work in which no figures appear at all.

Sutherland’s greatest achievement, however, is his profoundly moving series of war paintings, which end this superb and uplifting exhibition. Like Nash and Henry Moore, he’d been appointed an official war artist during the Second World War and his desolate scenes seem to suggest the destruction of something much deeper than the world that is manifest and visible. Devastation 1941: City, Twisted Girder, 1941 and Devastation, 1941: East End, Burnt Paper Warehouse are two such remarkable works on paper that leave this impression burning in the imagination.