A solid and interesting survey of the German artist, rather than a brilliant and thrilling one

In recent years it seems we have seen an awful lot of Gerhard Richter. There have been three major exhibitions in London within the last seven or eight years. One is hardly complaining, since there is always a demand to see “the world’s most influential living painter”, as he is often claimed to be (and not without some reason). But in each case these have, and with varied success, focused on one aspect of Richter’s output: portraits at the National Portrait Gallery, colour charts at the Serpentine, “scrapbook” photos, many obscured with paint, at the Whitechapel Gallery.

But Richter’s practice is characterised by its mastery of several genres and many styles: from small photorealist portraits to giant monochrome abstract canvases, from homely landscapes in a 19th-century northern European style to blurred black-and-white images that imitate the look of smudgy newspaper print.

Tate Modern’s survey is the first full retrospective of the German artist since his Tate Gallery survey 20 years ago. Richter’s homage to German Romanticism and the Sublime in that earlier exhibition – the roiling, grey seascapes and the intense, quietly powerful, part Catholic, part Zen candle paintings – are the encounters I remember with most clarity. But they hardly make anything like the impression they made then. Familiarity is one reason (the seductive first encounter that initiated a question: who else is painting like this now?) but also because here they’re not given a room to themselves but are placed, as are most of his figurative works, alongside large-scale abstract paintings in what is a loosely chronological hang.

These juxtapositions present a powerful dialogue, primarily about the plasticity of paint. But as for the abstract works themselves, as varied in colour and texture as many of them are, they eventually begin to feel like punctuations rather than further insights into Richter’s practice. There are, for instance, too many squeegee paintings – wet paint that has been rolled with a squeegee, creating striations, strips and blots of different hues and surface textures. Some of these, like the Forest series of the early 1990s, are arresting when encountered as a series: we see bright vertical marks of yellow or orange against layered blue grounds, which vaguely resemble vibrating sound waves turned on their sides. Richter remains deeply interested in the effects of chance, a legacy from the early Modernists.

Moving through the exhibition (curated by Nicholas Serota and Tate curator Mark Godfrey), you become acutely aware that you’re being earnestly guided to focus on the full range of processes and techniques at Richter’s disposal, rather than becoming merely absorbed in a search for meaning through subject and narrative – which is far more likely to happen in a thematic hang, of which Tate is usually so fond. Richter is a virtuoso, for sure, but I think this is exactly the kind of mixing, disruption and repetition that does Richter few favours.

This exhibition is bigger than the one two decades ago, but still feels somehow incomplete. And this makes it a solid and interesting survey, rather than a brilliant and thrilling one. Now 80, Richter’s career has been long and productive, so what to leave out and what to put in is always going to create interesting problems. But if one is broadly familiar with Richter’s work, one may still miss key pieces in such a substantial show. His painting of a distressed Jackie Kennedy, reeling from the shock of the assassination of her husband, is undoubtedly one of his most powerful portraits, but it doesn’t make an appearance. Nor do any of his related series of American political paintings.

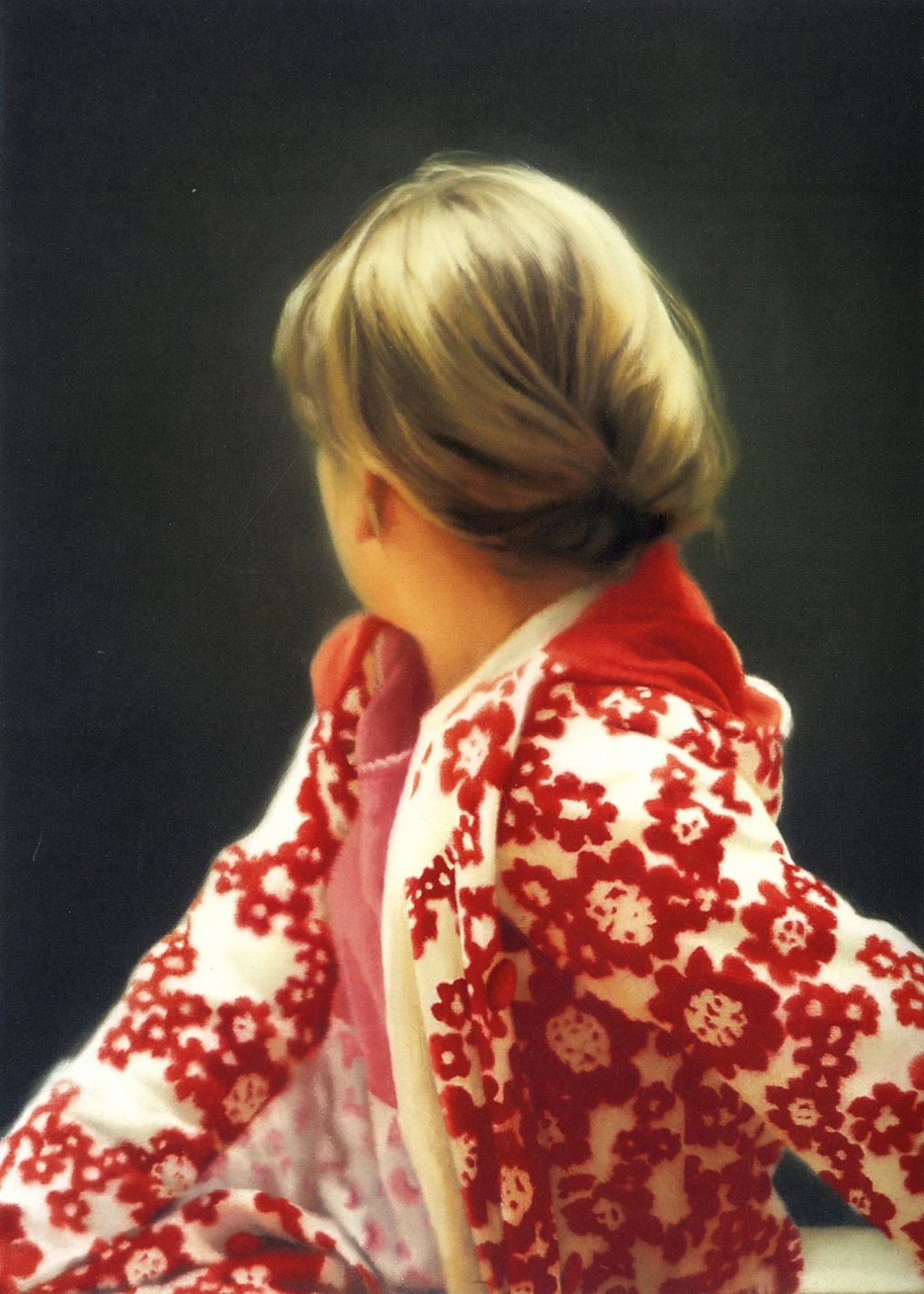

Some of his most justly celebrated portraits do: Betty, 1988, whose face is tantalisingly and eternally denied us, and the equally photographic Reader, 1994, after a painting by Vermeer. But how much do we really need to see a failed painting of a copy of a Titian (Annunciation after Titian, 1973), so smooth and bright and kitsch? Or all three of his massive cloud paintings, each a depiction of a single cloud in a grey-blue sky – minus the angels and cherubs?

Many of the early paintings from the late Sixties confront Germany’s recent history and are intimately linked to Richter’s own family history. These look back from a distance of 30-odd years from the original photographs on which the images are based. Two blurry greyscale paintings from 1965, Aunt Marianne and Uncle Rudi, are taken from family photos. A smiling girl, the picture of Aryan girlhood, is tending a restive baby (Gerhard). Later, suffering from mental illness, Marianne was forced to undergo sterilisation under the Nazi regime, then eventually killed. Uncle Rudi, meanwhile, smiles broadly for the camera in his dashing Wermstang overcoat. But he too will soon be dead, killed in battle within the first few weeks of the start of World War II.

Richter was born in Dresden in 1932, and the destruction of that city, and the ruination of other European cities, is another early theme. We see swarms of fighter aircraft, like Airfix models dispensing tiny pellets, and paintings of greyly indistinct rubble, which turn out to be topographical studies.

Often Richter’s gaze seems pitiless, but perhaps not always. In an image of his father, with whom he had almost no relationship, we see an old man with his hair in two tufty points that echo the ears of the small, button-eyed dog he is holding. He looks utterly ridiculous and yet we see the pity of it, the aching vulnerability in his round-eyed, bemused stare. Later the Baader-Meinhof gang, in a series of black-and-white paintings painted just over a decade after their deaths in custody, are shown in a room by themselves, the only series given a room of their own. Do we detect empathy here, too?

Sometimes Richter plays with double illusions: a car speeds past in a grey blur, but the trees are also depicted in a speed-blur. We cannot trust what we are seeing in relation to ourselves, for a moving object amid stationary objects are given the same blurry treatment. And distrusting what our eyes tell us is a key Richter concern. September, 2005, painted four years after 9/11, shows one of the Twin Towers about to be hit. But the blurry fragments only make sense in this apparently abstract image when we read the information accompanying the image.

This is an exhibition that shows us what an assured and supreme virtuoso Richter is, but it also shows us weaknesses. This rounded view may be a very good thing (however venerated, Richter is human after all). But a fuller retrospective would surely not have denied us a few more of the greats. And perhaps it would not have allowed so many of the clearly lesser abstract squeegees.