A new exhibition of avant-garde works from the 70s is a fascinating window into the anger that drove the movement – and a reminder of its continuing relevance

A woman stands at a butcher’s block, surrounded by kitchen implements that she slowly, methodically names in alphabetical order: apron, bowl, chopper etc. She wears an impassive expression, but as she demonstrates the use of each appliance her actions become increasingly aggressive, suggesting murderous intent. Brandishing a pair of knives, she signs off for the last letter of the alphabet with a Zorro-like flourish.

Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen (watch video below) is one of the seminal feminist artworks of the 1970s, and certainly one of the most anthologised. It will be shown at the Photographers’ Gallery in London from October until January, alongside the work of 47 other female artists working with photography and video, in an exhibition of feminist avant-garde works from that era. All are on loan from the Verbund Collection in Vienna, which specialises in avant-garde and conceptual art.

Many of the artists are well-known, such as Cindy Sherman, Francesca Woodman, Hannah Wilke and Judy Chicago, while some are ripe for rediscovery. Many of the works, such as Rosler’s grainy, 1976 video, tap into female rage, though Semiotics does undercut its righteous anger with subtle humour: it’s clearly a parody of the kind of cookery show that was popular across US TV networks, and the big shrug the artist gives at the end is deployed to further deflect that anger.

Yet, when it was first shown, there were many who felt deeply discomforted, even threatened. “Some men really found this work frightening when it came out and that surprised me at the time, since it seemed so obviously a kind of burlesque,” Rosler recalls.

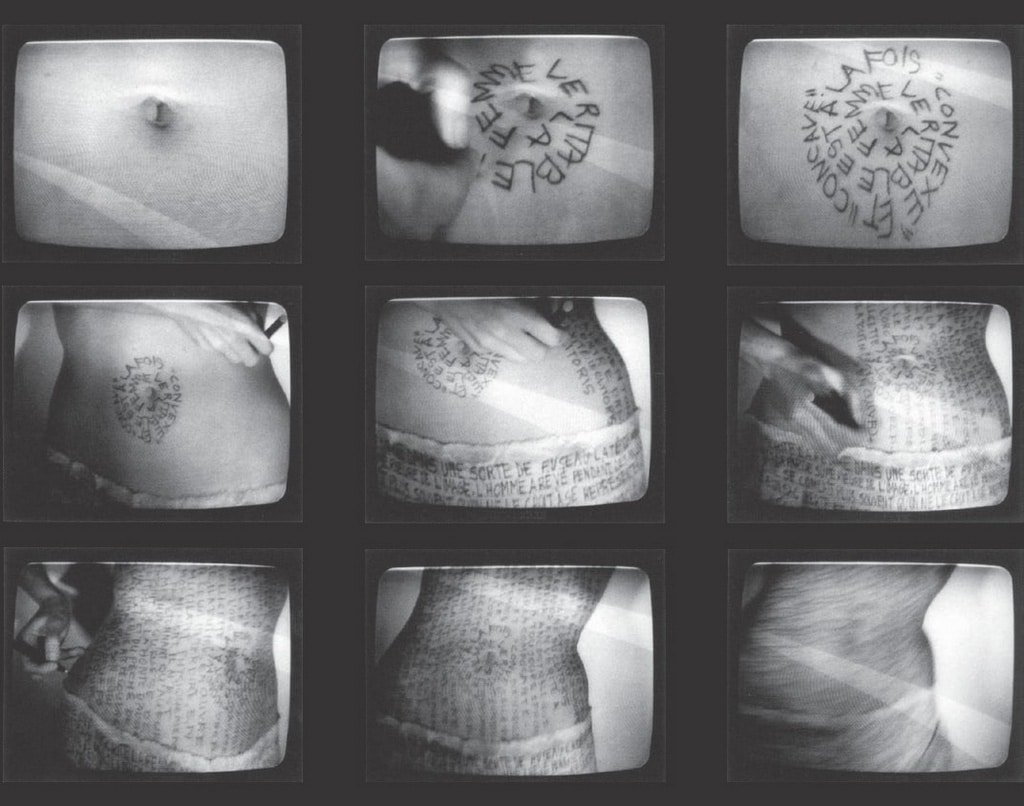

Though there isn’t much humour in Nil Yalter’s hugely influential 1974 film The Headless Woman (Belly Dance), it certainly exudes a simple and beguiling poetry. Yalter, an Egyptian-born Turkish artist who moved to Paris in 1965 and has lived there ever since, explores, like many of her American and European contemporaries, sexual objectification. Rather more uniquely, she explores orientalism. The object of our focus is a woman’s stomach on which text has been inscribed. As the woman begins her belly dance, all we see is the soft flesh of her undulating stomach, and the pulsing text.

The Headless Woman references an old Anatolian ritual of female sexual humiliation: a woman who did not obey her husband or who was unable to conceive would be bought before the village imam; her head and face would be covered and her belly inscribed with a prayer. “Very often, the iman would make a mistake and he would lick off the mistake with his tongue,” Yalter explains.

Like Rosler, Yalter recalls the hostile reception to her film. “The reaction was very aggressive from men,” she says. “You also have to remember that in America there was more feminist artistic activity. Here, we were not at the centre of that.” It’s hardly worth mentioning that in France some of the issues the work raised in relation to the Arab or Muslim female body are still depressingly apposite.

Although many of the works will no longer generate the hostile reactions they once did, some pieces even now retain an air of danger.

One artist whose work certainly hasn’t been tamed by time is VALIE EXPORT (the Austrian artist’s adopted name, after a brand of cigarettes, is capitalised). Photos in the exhibition recall her best-known performance, the aptly named Genital Panic, (1968), in which the artist wandered through a Munich arthouse cinema wearing crotchless trousers and a tight leather jacket. Her hair wild and unkempt, she no doubt resembled a feral predator as she roamed the rows of seated spectators, her exposed genitalia level with faces.

The infamous Genital Panic was certainly one way of gaining one-up-womanship with a contemporary Viennese art world then dominated by the often deeply misogynistic Vienna Actionists, whose acts of ritualised sadism sexually debased the female rather than the male body. In fact, you might say the same about the exhibition as a whole: that it’s a necessary display of defiant redress.