Eschewing the in-your-face aesthetics of his contemporaries, the reputation of the artist, who died of Aids aged 38, has only grown in the intervening years.

“I would say that when he was becoming less of a person I was loving him more. Every lesion he got I loved him more. Until the last second, I told him ‘I want to be there until your last breath,’ and I was there to his last breath.”

These are the words of the conceptual artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres in an interview he gave in 1995. He was talking about the Aids-related death of his partner Ross Laycock four years earlier. Less than a year after the interview, Gonzalez-Torres himself succumbed to the disease. He was 38.

Much of Gonzalez-Torres’s work relates to Laycock, who died just as the Cuban-born American artist’s star had begun its phenomenal rise in the art world (the interview, with American art journal Bomb, was given on the occasion of his solo exhibition at the Guggenheim, New York). Since then, there have been shows across America and Europe. In London, a posthumous survey was held at the Serpentine Gallery in 2000, with concurrent displays at the Victoria & Albert Museum, Camden Arts Centre, the Royal College of Art, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, and in various locations across the capital: his lightbulb garlands lit up streets in Camden and huge billboard posters, depicting two indented pillows on an unmade king-sized bed, towered above the traffic from Lambeth to Paddington.

Twenty years after his death, Gonzalez-Torres’s star hasn’t dimmed. In fact, his reputation continues to grow. In 2007, he represented the US in the Venice Biennale, and in 2010 one of his candy-pile pieces sold for $4.6m. Now he’s showing concurrently in three venues: London’s Hauser & Wirth, New York’s Andrea Rosen Gallery and Milan’s Massimo de Carlo. Each gallery focuses on different aspect of the artist’s output, with each exhibition curated by artists Roni Horn and Julie Ault. Both were close to the artist and are fellows of the Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation, formed in 2002. The Foundation is almost fanatically protective of the artist’s legacy: neither Horn nor Ault were willing to talk about their curatorial role, and after a week of painful to-ing and fro-ing finally changed their minds about even emailing a list of the works they’d chosen for each venue.

This apparent distrust of the press seems curiously at odds with the openness and generosity displayed by the artist throughout his short career, evidenced not only by his touching frankness in interviews, but by the work itself and the element of ritual in terms of the public’s intimate and physical interaction with it. The candy pieces evoke ideas of Catholic transubstantiation, but also something more erotically charged and subversive.

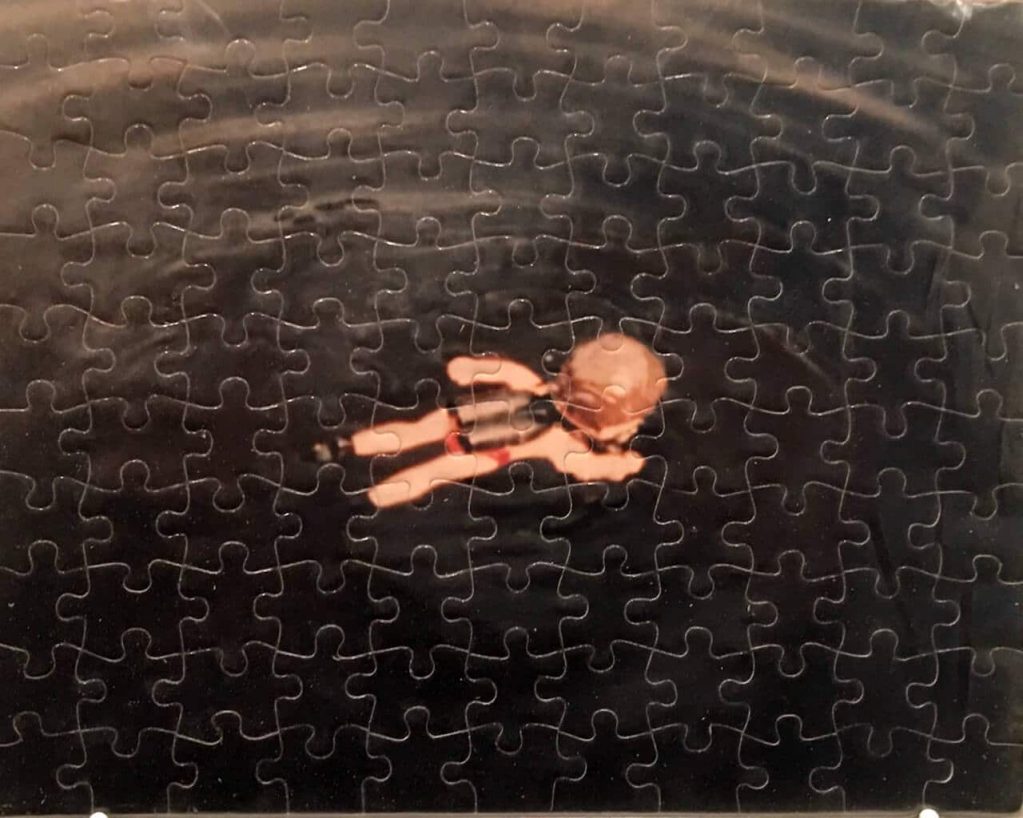

The American critic and curator Robert Storr acquired one of the artist’s best known candy works, “Untitled” (Placebo), for MoMA, New York, during his time as a senior curator at the museum. The 1991 work is a large rectangular carpet of candies wrapped in silver foil. It might look, at first glance, to be a typical minimalist floor piece or an example of late 60s scatter art, except that the piece shimmers and sparkles with the light and you’re welcome to eat the candies. “Each candy is essentially a kind of host,” Storr explains, “a surrogate for a body that’s not there, because the weight of those candies represents the weight of Ross, who had already died of Aids, and of Felix himself, who was dying of Aids. So as you consumed the candy you were consuming the body and the blood of an Aids patient, and you were also sucking, in a public place, the substance of two men who had been lovers.”

It is, then, a work that’s both playfully teasing and deadly serious, especially given the climate of hysteria and ignorance surrounding Aids at the time. Subtly but powerfully, Gonzalez-Torres was offering up the Aids patient as the culture’s sacrificial martyr. The work also encompassed ideas about renewal (resurrection even), since the depleted candy stock was regularly replenished. And at a time when the existence of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) was constantly under political threat as a funding body for artists openly embracing “transgressive” themes to do with sexuality and sexual identity, Gonzalez-Torres’s work made no attempts to shock. Instead, in its coolly minimal way, it employed strategies to engage, rather than repel, the viewer.

This being the case, it won’t come as a surprise that Gonzalez-Torres once said he “had a problem with what’s expected of us”, meaning that he resisted giving what a straight and fairly conservative society expected to see from gay male artists. While his contemporary Ron Athey, in one notorious performance, soaked pieces of cloth with the freshly drawn HIV-infected blood of a fellow artist, which were then floated above the heads of the panicking audience, Gonzalez-Torres’s instead invited the viewer to walk through a curtain of red beads. Gonzalez-Torres felt that it was neither necessary nor effective to employ so-called “in-your-face” tactics.

“The thing that I want to do sometimes with some of the pieces about homosexual desire is to be more inclusive,” he said. So a work like “(Untitled)” Golden (1995) with its silky curtain of tiny yellow beads, evokes an esoteric sexual practice without threatening the audience. “We also have to trust the viewer and trust the power of the object. And the power is in simple things,” González-Torres said.

Instead of deploying aggressive tactics, Gonzalez-Torres created powerful metaphors, using them to focus, in complex and often oblique ways, on social issues, from Aids to gun culture to poverty and sexual and marginal identities. Hence, simply two clocks telling exactly the same time, in “Untitled” (Perfect Lovers).

Storr, who was the curator of the Venice Biennale the year Gonzalez-Torres was chosen, is confident that the artist is one of the most important to have emerged in the 90s, as groundbreaking and enduring a figure, he says, as Eva Hesse was in the 60s and 70s (Hesse also died young, from a brain tumour). “Felix’s gift as an artist was that he understood the power of subtlety,” he says. “When everybody’s screaming, whisper, and people will listen.”