From James Ensor to René Magritte, too many Belgian artists have been erroneously associated with Surrealism. In fact, their compatriot artist Luc Tuymans tells Fisun Güner, it is realism that is at the core of their imagery, an attribute that can be traced all the way back to Van Eyck.

With his solemn face and sorrowful gaze, here is a young Belgian painter surrounded by a sea of grotesque masks. He stares at us. We stare back. Are his eyes accusing us of some unspecified crime against him, or simply imploring us to bear witness to his suffering? Improbably he wears a hat with feminine trimmings: a large, drooping plume, like a cock’s tail, showy and ridiculous, and an abundance of roses pinned to the front. In some ways, the scene calls to mind the Inquisition: he could be a Christian martyr in a dunce’s cap. Or perhaps he is Christ himself, taunted by the rabble of mummers who jostle and persecute him. Yet the crowd leaves him looking somehow untouchable, as if he is really not of their world, nor of ours.

James Ensor (1860-1949) was 39 when he painted Self-Portrait with Masks (1899), yet it is full of a young man’s existential persecution complex. It hints at hubris and narcissism, which was presumably fed in part by a lack of recognition as an artist (success was to come much later, with national honours, critical acclaim and, with the title of baron, royal approval too, when he was well past middle age). Until he was 57, he lived and worked above his mother’s crowded souvenir shop in the cold, coastal town of Ostend, a town in which he was born and in which he died aged 89 and which – apart from a period in Brussels in his youth, when he trained as the Royal Academy of Arts – he rarely left.

‘What I find quite shocking,’ says the (also Belgian-born) artist Luc Tuymans, who is curator of a survey of Ensor’s work at the Royal Academy in London this autumn, ‘is how underappreciated he is in Britain. It’s especially ironic, since his father was British, and he himself became a Belgian national only when he was made a baron. It’s probably to do with you guys living on an island.’

Compared with his Norwegian contemporary Edvard Munch (1863-1944), another Northern European proto-Expressionist, Ensor is not well known in the UK. And yet the half-English Belgian has an almost cultish following outside his native country, not least for his gruesome fin-de-siècle mask paintings. Major exhibitions of Ensor’s work have been mounted in New York, France and Germany in recent years, but – apart from a show at the Lady Lever Art Gallery in the Wirral in 2007, which centred on one painting, Old Lady with Masks (1889), and featured 30 engravings from Ghent’s Museum of Fine Arts – nothing has been seen in the UK for almost two decades. It is only thanks to the closure, for restoration, of Antwerp’s Royal Museum of Fine Arts that we can now enjoy its extensive Ensor collection, topped up by brilliant loans of paintings, etchings and drawings – Ensor was an astonishingly gifted draughtsman – from Brussels, Ghent and Bruges.

‘It will be a more complex take on Ensor than most people are used to,’ Tuymans tells me from his studio in Antwerp. ‘It will show up his diversity in his themes. There’s a clear political stance in his work, as well as an anti-religious one that takes on a very sardonic mood. It is not a big show, but the works are of a super quality, and one of the challenges in such a focused show is to put him in a context that is social and political. There was a lot of social unrest in Belgium, which was still a very new country at that time, having been formed only in 1830.’

Ensor often portrayed himself as either skeleton or Christ, his best-known painting being The Entry of Christ into Brussels in 1889, (1888), a big, cinemascopic canvas painted a year before Self-Portrait with Masks. Here Christ, small and barely discernible amid a heaving, swarming maelstrom of carnival grotesques, is entering the city on a donkey. We can just about make him out by his halo and an arm raised in benediction. Dominating the scene are commercial and political banners, of which the largest can be translated as ‘Long Live the Socialist State’, while another advertises Colman’s Mustard. Elevated themes are undercut by base one. It’s a seeming hotchpotch, but it might be read as partly a satire on populist politics and partly an exposé of religious hypocrisy. Either way, damned be the foolish citizenry who champion their own vested interests, it appears to be saying. It’s a shame this seminal canvas, which belongs to the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, is not in the exhibition.

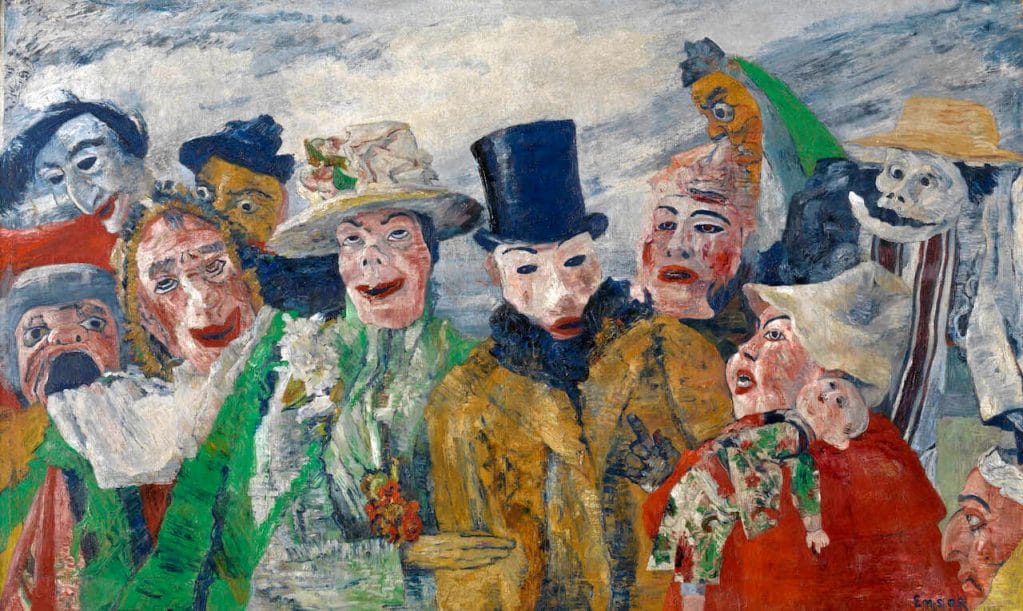

The RA show will, however, include an important painting called Intrigue, after which the exhibition takes its title: a grotesque manifestation of bourgeois society featuring pantomime gargoyles – preening yet suspicious, hemmed-in, each protective of their own bit of cramped social space. Less grandiose than The Entry of Christ, it has, says Tuymans, ‘the same intensity and element of danger.’ The painting, in its striking immediacy, and with its characters eliminating the foreground (eliminating the space between us and them) made a deep impression on the teenaged Tuymans. He notes its fiery Rubens-esque colours. ‘It’s a powerful work in its colour division, its modernity and roughness, in its tension between brutality and refinement.’

It was painted two years after The Entry of Christ, and you can see how these disjointed, alienated figures, in their compacted urban space, might have had an impact on the avant-garde CoBrA group, co-founded by Belgian artist Christian Dotremont (1922-79) some 60 years later.

Named after the initials of the capital cities of its founders’ native countries, Copenhagen, Brussels and Amsterdam, this was an international movement of artists who deplored naturalism and found abstraction ‘sterile’, believing instead that work should be spontaneous, free, and spring from the unconscious. In fact, rather more than the rough, graffiti-like, crudely child-like paintings of the Northern European CoBrA, Ensor’s work has often been viewed as proto-Surrealist, his fantastical imagery taking us in direct line from Hieronymus Bosch in the 15th and 16th centuries to René Magritte in the 20th.

Yet Tuymans insists this reading is incorrect, both of Ensor and of artists he says are erroneously associated with Belgian Surrealism in the 20th century. Tuymans returns to the newness of Belgium as a nation state and the effect this had on its culture. ‘It had been ruled and overruled by several powers, so we never had time to be Romantic, unlike the Germans – or megalomanic, like the French,’ he asserts.

‘There has always been this element of survival and opportunism simply in terms of staying alive. This means that the element of real and realism is much more at the core of our imagery than Surrealism, and this starts all the way back to [the early Northern Renaissance painter Jan] Van Eyck [who is thought to have been born in the Limburg province of what is now Belgium in c.1300]. Ensor really paints what he sees, rather than painting from his imagination, and offers a social and political critique, grounded ultimately in the real.’ The imagery may be heightened by an expressive, satirical palette, but it is not proto-Surrealist, he insists.

As for Magritte (1898-1967), the artist most associated with Belgium, he too painted ‘the real’, says Tuymans. Tuymans argues that the Surrealist tag is a misnomer. ‘When you have a work that declares, “This is not a pipe” and you find the title is The Treachery of Images (painted 1928-30), you know that this is really about the real, because, of course, it’s not a pipe, it’s an image of a pipe. This principal difference [in thinking] was the reason that in 1925 Magritte broke up with [the French writer, Dadaist, and originator of the Surrealist Manifesto], André Breton, the movement’s intellectual founder. Belgian artists are generally individuals. They are not really part of movements.’

Ensor, however, who had mixed in avant-garde and intellectual circles in his youth, did help establish, if not as anything as coherently defined as a ‘movement’, a loose affiliation of young Belgian artists who sought to find success by exhibiting together and by inviting avant-garde artists from Paris to exhibit with them.

The group was called Les XX, and one of the primary motives for its formation was the rejection of Ensor’s early, naturalistic The Oyster Eater in 1883 by two established salons. But, typical to form, Ensor soon quarrelled with the group, resisting their interest in Impressionism, and later firmly and angrily rejecting their adoption of Pointillism or Neo-Impressionism, a technique developed by Georges Seurat and Paul Signac whereby tiny dabs of pure colour mixed optically to form the coherent image. This precise, meticulously scientific technique was an anathema to Ensor. After the split, he only occasionally travelled to Brussels, and rarely further. Instead, his mother’s shop, crammed with chinaware, taxidermy and grotesque carnival masks, became the focus of his world, and the masks, arranged with garments to suggest a ragged body, his gurning studio models.

Holed up in this attic studio, surrounding by his props and drinking very heavily, as his father had done, Ensor tends to be cast as an artist whose early but not later work can be considered great. After the age of 40, he more or less settled into repeating motifs and copying many of the paintings he made as a younger man. Eventually, in solitude and boredom, his passion shifted to composing music. This he took very seriously, forcing others to listen to his compositions but ultimately failing to convince anyone of his greatness in that field.

So how far did his talent as a painter decline? ‘It was a very lightening career in a sense,’ Tuymans says. ‘But it’s by no means the case that there is no work from a later date that doesn’t have specific qualities. It’s just different. And, of course, you have to see it from the point of view at the time, of when it was made. In those days, as opposed to now, for an artist to acquire a style was something which was important – it was how you were identified. You had a definite style and were not always striving for the new.’

Tuymans, who has long had an interest in the history of Belgian art and recently curated an exhibition in London of postwar Belgian abstraction, is keen to introduce another Belgian painter to a wider public: Léon Spilliaert, like Ensor an Ostender, though two decades younger. Spilliaert’s disquieting Symbolist portraits, with their chilly, subdued palette, convey a darkly uneasy mood associated with Northern European painting at the turn of the 20th century. He is an artist, like Ensor, who, though embedded in reality – in his depiction of recognisable street scenes and well-appointed interiors – makes the real seem very strange indeed.

As for Tuymans, who will be represented by one painting in this exhibition, his pale, thinly painted ‘ghost’ portraits, often of famous historical figures or well-known contemporary faces, surely continue in that powerful tradition.