Surrealism and the female artist: Dreamers Awake explores how the female body was reclaimed and the Surrealist male gaze subverted

Let’s deal with what’s bad first. There are 169 works in this exhibition by more than 50 artists. They’re arranged on walls, on plinths, in clusters. And there are no wall labels. Is it wrong to moan about this? It’s a perennial bugbear. Dreamers Awake is a sprawling four-gallery survey of female artists influenced by Surrealism, and it’s not enhanced by having to consult eight pages of layout and haplessly try to match the numbers on a diagram to the numbered lists below. Even if you recognise the work of many of the artists – and so what if you do? – this is a source of irritation.

The White Cube is a commercial space not a public gallery or museum, but it does, like the Gagosian (which isn’t at all sniffy about common or garden wall labels), put on tremendously ambitious and otherwise brilliantly curated exhibitions which have a ‘museum quality’ feel and which you’d expect to have a larger-than-average visitor number. So why do curators put us through this unnecessary torment? Do they not like us? Hopefully it will one day filter through to the right people that wall labels are our friend.

Frustration aside, there’s so much that is right with this exhibition. It takes us from the female artists who were associated with the Surrealist movement in the 1930s to contemporary artists riffing on Surrealist motifs and making playful and punning juxtapositions exploring sexuality, eroticism and gender. There are some cracking artists, some who are very familiar, some less so, with works that are displayed so that they’re in constant dialogue with each other.

And of course it’s an exhibition that’s partly about taking back ownership of the body, for it’s not only predominantly male artists who have always objectified the female body, but it was the Surrealist male gaze that turned it into a literal and metaphorical object, from Man Ray’s Le Violon d’Ingres to Dali’s Venus de Milo with Drawers. The male Surrealist has dismembered, beheaded, trussed up, dislocated, hybridised, mutated and mutilated the female form. Think of Magritte’s Rape, which transposes the female torso onto a face, and Hans Bellmer’s creepy-as-hell pre-pubescent dolls whose limbs and torsos are put together in odd combinations and whose broken and bizarrely reconstructed bodies are often displayed in the crepuscular gloom of forest and undergrowth to further suggest defilement and murder.

Sexual violence done to women as an act of liberating unconscious desires of the universal male psyche are Surrealist in essence. Given this, one might say that Surrealism is in part the psychic and aesthetic embodiment of the hate-versus-worship-versus-fear of the female. One of the most disturbing images in the exhibition confronts this idea with a force and violence equal to anything produced by a male counterpart and it’s by an artist who was the Surrealist muse par excellence, one who was painted by Picasso and photographed endlessly by her lover Man Ray. Lee Miller’s Untitled (Severed Breast from Radical Mastectomy), 1930, shows two severed breasts on two dinner plates like two meat pies that are undercooked and overstuffed with a rich serving of gristle. Perhaps Miller always felt, in a sense, cannibalised herself by male desire. Here the breast has been brutally unsexed and deconsecrated as an object of worship.

Other artists of the Surrealist movement, as well as those painters simply associated with its first wave, include Leonora Carrington, Dorothea Tanning, Leonor Fini, Edith Rimmington and Ithell Colquhoun, the latter represented by a painting, Tree Anatomy, 1942, in which a tree hollow turns into a vaginal cavity, with labial folds and a neat pubic bush.

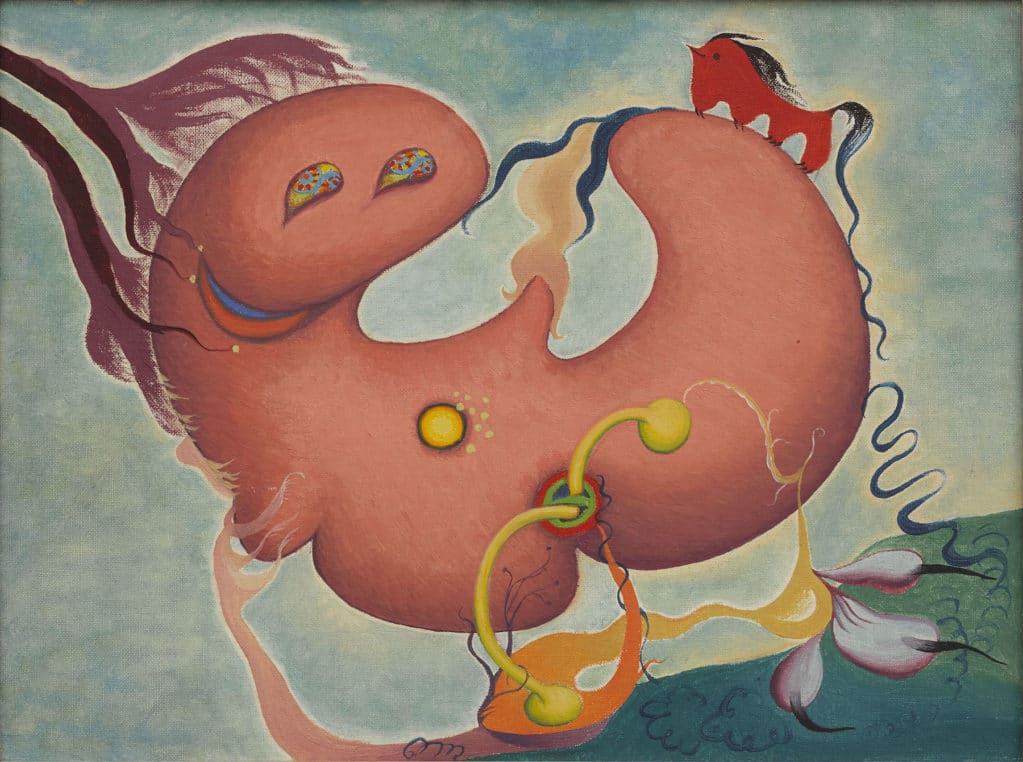

Leonora Carrington, (Title Unknown), 1963 © Estate of Leonora Carrington. Courtesy Private Collection, London

Vaginas are secreted here and there. Hannah Wilkie’s The Five Androgynous Vaginal Sculptures, 1960, are small terracotta vessels, each one a different shape, that might have just been excavated from some ancient site, while Mona Hatoum’s cabinet of glass vaginas are objects of cool, sterile beauty. Meanwhile, Rosemarie Trockel has stuck a great fat tarantula on the mons pubis of Courbet’s The Origin of the World (not so inviting now), and nearby we find Hatoum’s Jardin Public, which is frankly a terrible pun and consists of a wrought iron garden chair with a tuft of pubic hair placed on the seat. Next to it is Sarah Lucas’s The Kiss, 2003, two chairs entangled, cigarette-covered breasts on one chair, a cigarette-covered cock coming up from the seat and the size of a prize-winning marrow on the other. And if knobbly gourds bring a smile to your face, you’ll be tickled by Helen Chadwick’s prickly bronze casts of them encircled by furry rings in I Thee Wed, 1993. Naturally they bring to mind Meret Oppenheim’s furry cup and saucer, which no sexual pun has ever bettered.

The fruit-flower-vagina trope is perfected by Nevine Mahmoud’s marble and alabaster sculptures, but by now things are probably getting a little predictable. It’s good to see Francesca Woodman, whatever the context, while Carina Brandes’ beguiling black and white images clearly follow in her footsteps. There’s a lot of recent work, not surprising since the gallery is showing their own artists, but it’s the original Surrealists that probably still excite the most, from Carrington’s wild folkloric beasts to Claude Cahun’s striking self-inventions.