Close clearly relishes unveiling the method behind the illusion, the trickery behind the magic

Chuck Close is often described as a photorealist. It’s a fair description. His paintings often look like photographs, and he came to prominence in the late Sixties, when photorealism was the rage. At first his huge heads were scaled-up painted transcriptions of black and white photos, such as Big Self-Portrait, 1968, which is the painting you’ll find in most art history accounts of the period. It captures a kind of rough diamond Easy Rider persona. Then he turned to colour and painted his huge heads as if they were seen through the distorting prism of a bathroom window. Or for those with a mind to the digital age, as if they were low-grade pixelated screen shots.

For those who are fair-to-middling in their opinion of Close, they will, I believe, be deeply impressed by this travelling survey of Close’s prints (it’s been touring America for the past decade). Featuring some 150 works, the exhibition documents just how complex and labour-intensive many of his processes are and just how much manipulation an image undergoes at various stages of its making. And as the title, Process and Collaboration, suggests, it’s a collaborative process. Close works with a team of printmakers and it’s a real eye-opener to be introduced to the range of techniques, some very old, some relatively new and experimental, and some arrived at simply by chance and accident, that he has explored throughout his career.

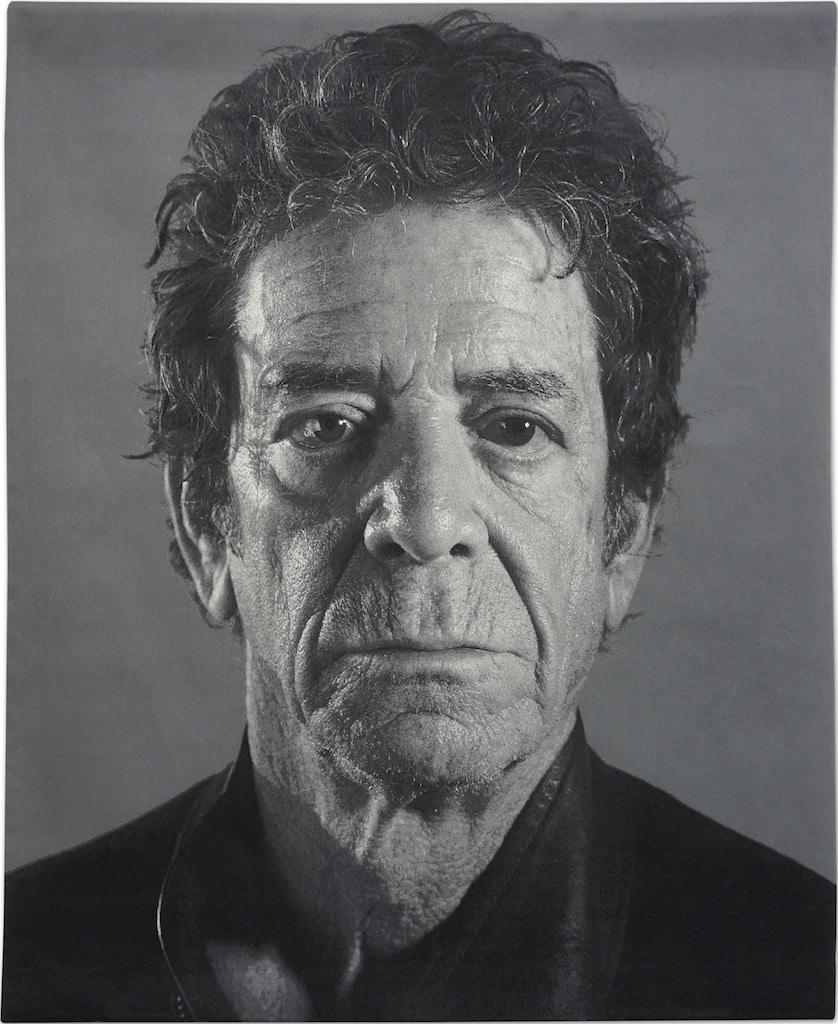

This museum quality show takes us from the velvety mezzotints of Keith, his earliest foray into print-making, to the startlingly photo-like tapestries featuring Lou Reed and Roy Lichtenstein. Etchings, engravings, Japanese wood-block prints, grey-scale paper pulp editions, silkscreens, and bulkily built-up collages – each process is ceaselessly explored for its range of possibilities. Often the same image will undergo the same process again and again, offering variations in tone, depth, texture. Like his gridded lozenge paintings, individual cells coalesce to form the image as you move away, taking us from abstraction to representation. Close clearly relishes unveiling the method behind the illusion, the trickery behind the magic, and so do we.

His exploration of the face, his own and that of his friends, is almost brutal in its hunger to interrogate every line and sag amid the pitted surface. And he gets pitilessly close to his subject. Squared off and isolated, nothing detracts from the face. Reed looks like some menacing lizard man, Philip Glass, another good friend of the artist, as if he’s sizing us up in return. Mouth slightly agape, eyes heavy-lidded, Glass’s scaled-up visage looks down at us as we look up, feeling a little small in comparison. It’s a face that appears kinder the craggier it’s got, whereas Reed looks perennially scary.

Unlike Warhol’s Superstars, in which the concentration of the lens for minutes at a time strips the subject of its mask, in Close’s work we interrogate the mask presented in a snapshot that took a second to take. But the snapshot remade reveals its own fascinations. The face becomes vast, virgin territory and we its explorers.