A 19th-century bookseller's encounter with a Velázquez portrait of a young Charles I changed - then ruined.

“The handling is free in the extreme, the brush appears to have swept across the canvas and never paused or hesitated… Even when the colour is most solid it is always thin, and in many parts it looks as if it had been floated on.”

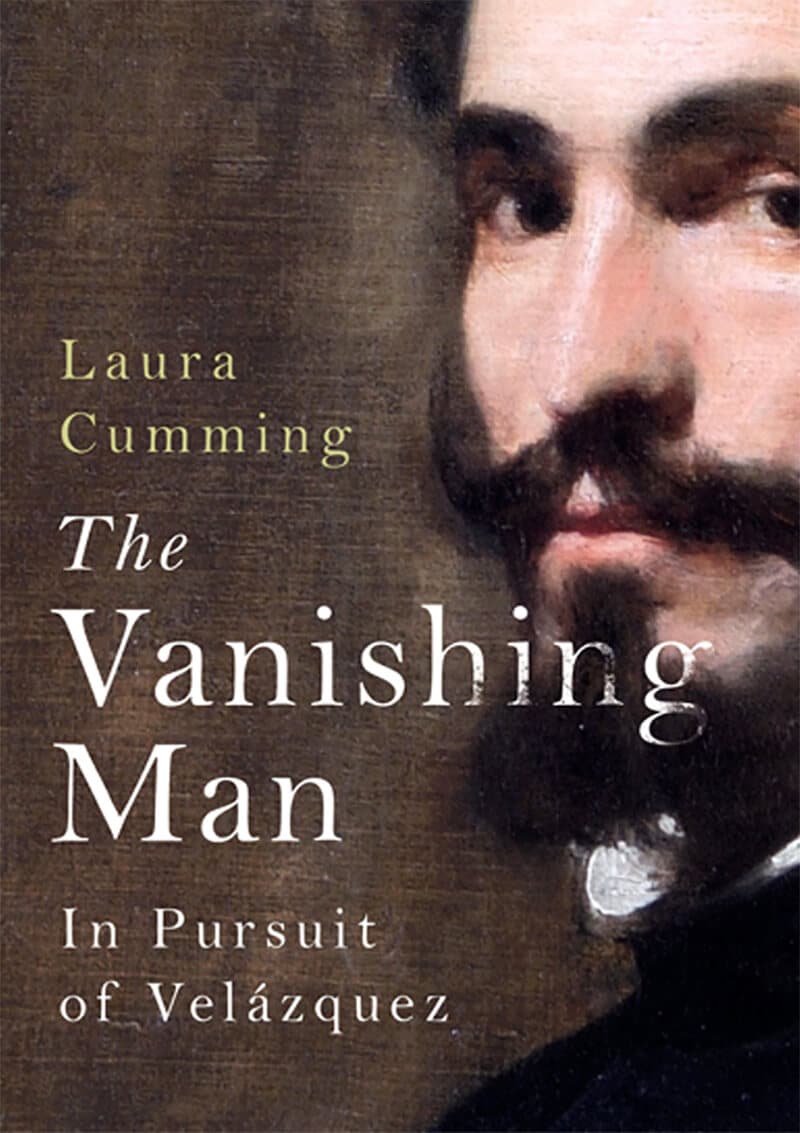

These are not the words of art cognoscenti, for such persons get short shrift in The Vanishing Man: In Pursuit of Velázquez, a real-life detective story involving an Old Master portrait of an ill-fated English king and an art obsession that would lead to the ruin of one of the book’s two mysterious protagonists: one a humble 19th-century printer and bookseller from Reading, John Snare; the other the great 17th-century Spanish court painter named in the title.

The words come from a self-published pamphlet, “Proofs of the Authenticity of the Portrait of Prince Charles”, written by Snare. Cumming comments on “how perfectly” Snare’s words “put the Velázquez effect”. In 1845, at an Oxfordshire country house auction, Snare had put in a bid for a lot 72, and for the unprincely sum of £8 – in an action that would eventually prove his undoing – he became the owner of a painting whose blackened surface carried the grime, grease and ingrained dust of two centuries. Having never been cleaned or restored, it was sold in what is still quaintly called “a country-house condition”.

But Snare knew he had something special – far more special even than the Van Dyck that many of the experts that soon got wind of the painting presumed. Snare had not been publicity shy with his acquisition. He had been more than happy to sell tickets and invite guests to show off his purchase – though it was hardly the money he was interested in, for he would never part with it, not even to save himself from bankruptcy. As Cumming nicely illustrates, it was a bit of art showmanship that was hardly unusual for the time, with travelling one-work shows vying with novelty acts, freak shows and other dazzlements to cheer the crowds.

Yet another of the Flemish artist’s portraits of Charles I would be very nice indeed (Van Dyck had been the King’s chief painter from 1632 until the artist’s death in 1641). But, wait, a Velázquez? Painted when the 22-year-old heir had paid an impromptu visit to the court of Philip IV in the hope of arranging a suitable marriage with the young Infanta Maria Anna? That would be inestimable.

The Spanish Match, as it came to be known, came to nothing – the whole affair had turned pretty much into a farce, and by all accounts Charles had outstayed his welcome. But at least one good thing had come out of it, if not for Charles – for whom it must have been a humiliation – then for posterity, in the shape of a portrait of unsurpassed sensitivity and startling naturalism.

The painting clearly showed the young Prince complete with a recently grown Spanish beard, but his bearing had none of the swagger and dash associated with many of Van Dyck’s portraits of the fashionable royal. Here he had a far more sober, penetrating gaze. The subject stood, in quarter profile, right up close to the viewer – and Velázquez masterfully did away with traditional pictorial space, as if the young prince were no longer anchored by material effects. This was an indeterminate space that the viewer could more readily enter, psychologically and emotionally.

By the mid-19th century, Velázquez was enjoying a growing reputation outside Spain, yet hardly any of his works were actually known outside that country, let alone seen at first hand. The Prado housed his greatest masterpiece, Las Meninas, which must undoubtedly be the most complex if not the greatest painting of a royal household ever painted, but the museum had opened its doors only in 1819. Cumming describes a much later visit to the Prado by Velázquez’s great French artistic heir, Edouard Manet, in 1865 – and even such a relatively short, landlocked trip to Madrid from Paris was no picnic. Manet was far too used to his creature comforts, though the revelation of the visit had changed the French artist’s life, and the course of modern art, incalculably.

Yet there were experts who presumed to know Velázquez’s hand intimately. The most notable among them was the well-regarded Stirling Maxwell, art historian and later Tory member of Parliament. In 1848 he published Annals of the Artists of Spain, an important, pioneering work, yet in it he readily dismissed the possibility that Snare’s painting could indeed be a Velázquez portrait of the young Charles, or indeed a Velázquez painting at all. Maxwell, Cumming writes, had “darkly implied that Snare might even be trying to raise his social standing by linking his name with that of the mighty Velázquez”.

The painting had belonged to the late 2nd Earl Fife, who had evidently never known what he had in his possession. With a dab of spittle on an index finger gently dabbed at a tiny portion of the surface – becoming instantly aware that he would have to be careful not to repeat the corrosive action in future – Snare revealed a segment of the luminous portrait beneath. If his concerns were to do with money or status, as Maxwell suggested, then he would not have kept the painting with him through thick and thin, certainly not through a ruinous legal trial actioned by the trustees of the earl’s estate. The claim that the painting had been stolen was a trumped-up, opportunistic charge, but Snare paid for it in more ways than merely financial.

Interwoven into the narrative of Snare’s tribulations, and of beautifully compelling accounts of Velázquez’s paintings, are moving snippets of biography that reveal Cumming’s own relationship to the great Spanish master. It is clear that the writer identifies with Snare’s passionate and personal response to painting, rather then a dispassionate and detached one exemplified by the Stirling Maxwells of this world. She talks of how grief at the loss of her artist father led her to a first encounter with Las Meninas, and those who have read Cumming’s first book, A Face to the World: On Self-Portraits, will already know what a thrilling account she gives of that work. The sensitive portrait of the 22-year-old Charles, is, incidentally, still lost to us. Who knows where, when or if it might turn up again. But paintings do.