Slimmed down from its appearance at David Zwirner in New York, a show of paintings by Alice Neel curated by Hilton Als, arrives in London, at Victoria Miro

Alice Neel lived in Spanish Harlem for the best part of 24 years. Singing its praises in a poem that simply began, “I love you Harlem,” she went on to embrace its “abandoned and despised”, to celebrate its mothers, with their “teeth missing” and “little black arms around their necks” and to draw the attention to the “rich deep vein of human feeling” to be found buried under all that urban bustle.

El Barrio’s cheek-by-jowl living and its ethnic mix, with many of its newer inhabitants arriving from Puerto Rica, as well as Dominica, Cuba, and Mexico, chimed with Neel’s artistic values as a painter of human life and coalesced with her political convictions. She’d been a leftwinger all her hard, struggling life, and though she never joined the Communist Party she was later, in common with many leftist writers and artists, briefly surveilled by the FBI. White, educated, and in pursuit of that “deep vein of human feeling”, Neel settled in East Harlem, with her Puerto Rican partner at the time, in 1938. That relationship wasn’t to last, as it proved with nearly all the men in her life, and she bought up her two sons from different relationships largely on her own, surviving on the financial support of friends. Recognition didn’t arrive until the late 60s, when she herself was almost 70.

That paean to her neighbourhood, which you can find in the catalogue to the current exhibition at Victoria Miro, was written just after the war and through the eyes of someone by now on intimate terms with her corner of working-class Upper Manhattan (Neel had moved from Greenwich Village, which by then was already a bohemian hangout full of artists, so it might appear she was deliberately cutting herself off from that cultural milieu).

Julie and the Doll, 1943, all images © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy David Zwirner, New York/London and Victoria Miro, London

The poem’s simplicity, the directness of its full-tilt, wide-eyed embrace, isn’t really echoed in her painting, or not entirely. What’s so much more striking in these portraits is the sense of both empathy and detachment, of both intimacy and awkwardness. Neel’s gaze could be warm – an impression often facilitated by the domestic setting of the artist’s own home – or it could be coolly forensic. You often feel a sensibility that alternates between the two, which is why I think you often sense the off-stage presence of the artist herself. There’s a drama, a relational dynamic.

Curated by the Pulitzer Prize-winning New Yorker theatre critic Hilton Als, the exhibition arrives from David Zwirner gallery in New York, but in a vastly slimmed down version: just 16 paintings from the 45 or so canvases (plus numerous drawings) at Zwirner. Here it’s 15 portraits, plus a painting of an apartment block from 1945, the latter exuding its own character with its imposing wonkiness. It presents the work on the gallery’s two floors, the ground floor showing work painted in East Harlem from the 1940s to the early 60s, while the second floor presents paintings from 1964 to 1976, after Neel moved to a new apartment in the Upper West Side (her landlord repossessed the third of her East Harlem apartments after some 20 years’ residence).

The difference between the lower floor and the upper floor is immediately apparent, not least in the brighter, light-infused palette, and the freer brushwork of the later paintings. The new apartment was simply more light-filled, but perhaps this change also reflected a lightness which Neel felt within herself as her fortunes changed. This was a period in which she was finally becoming a force within the art world. In 1974 she was given a retrospective at the Whitney; two years later, the date of the final portrait in the exhibition, she was elected to the American Academy and the Institute of Arts and Letters; and three years after that, and just five years short of her death aged 84, she was presented with a National Women’s Caucus for Art award for outstanding achievement by President Carter.

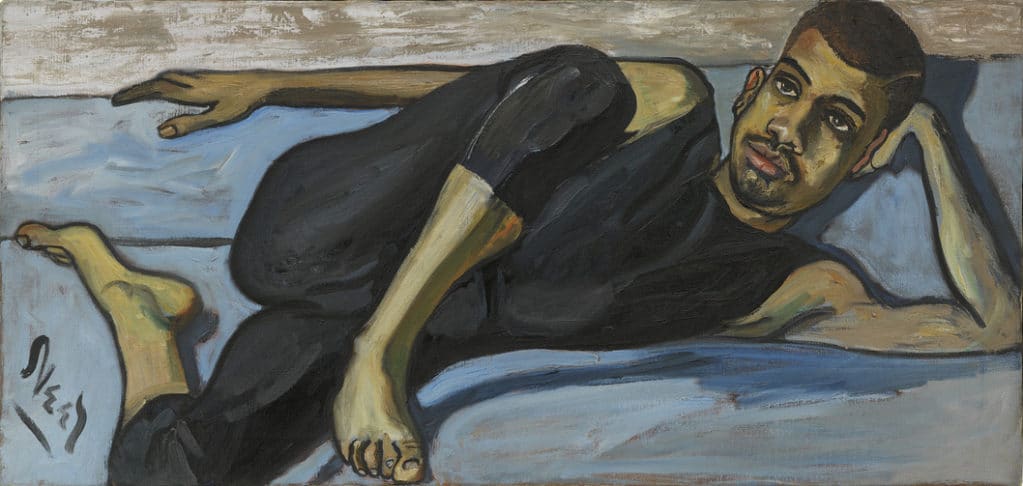

But I don’t think it’s just immediate circumstantial changes that are reflected in the paintings. Stylistically they alter as fashions in art change, so even though most of her working life was spent outside the fashionable art world milieu – kicking against formalism and abstraction – the paintings themselves are dateable not just by the changing fashions of the sitters, but through various stylistic evolutions in art. The earlier paintings have an appropriately stylised and naïf Kitchen Sink/Ashcan school look where even the whites of the eyes have a dull, sallow-coloured flatness to them. Girl with Pink Flower, c.1940s, and Julie and the Doll, 1943, are all heavy contours and thick outlines, and they possess a heavy-set angularity, which is especially notable in the first painting. But by 1950 the palette is not only lifting, but her sitters lounge and pose and gesture more freely, an example being the elastically contorted frame of the young black man in Ballet Dancer.

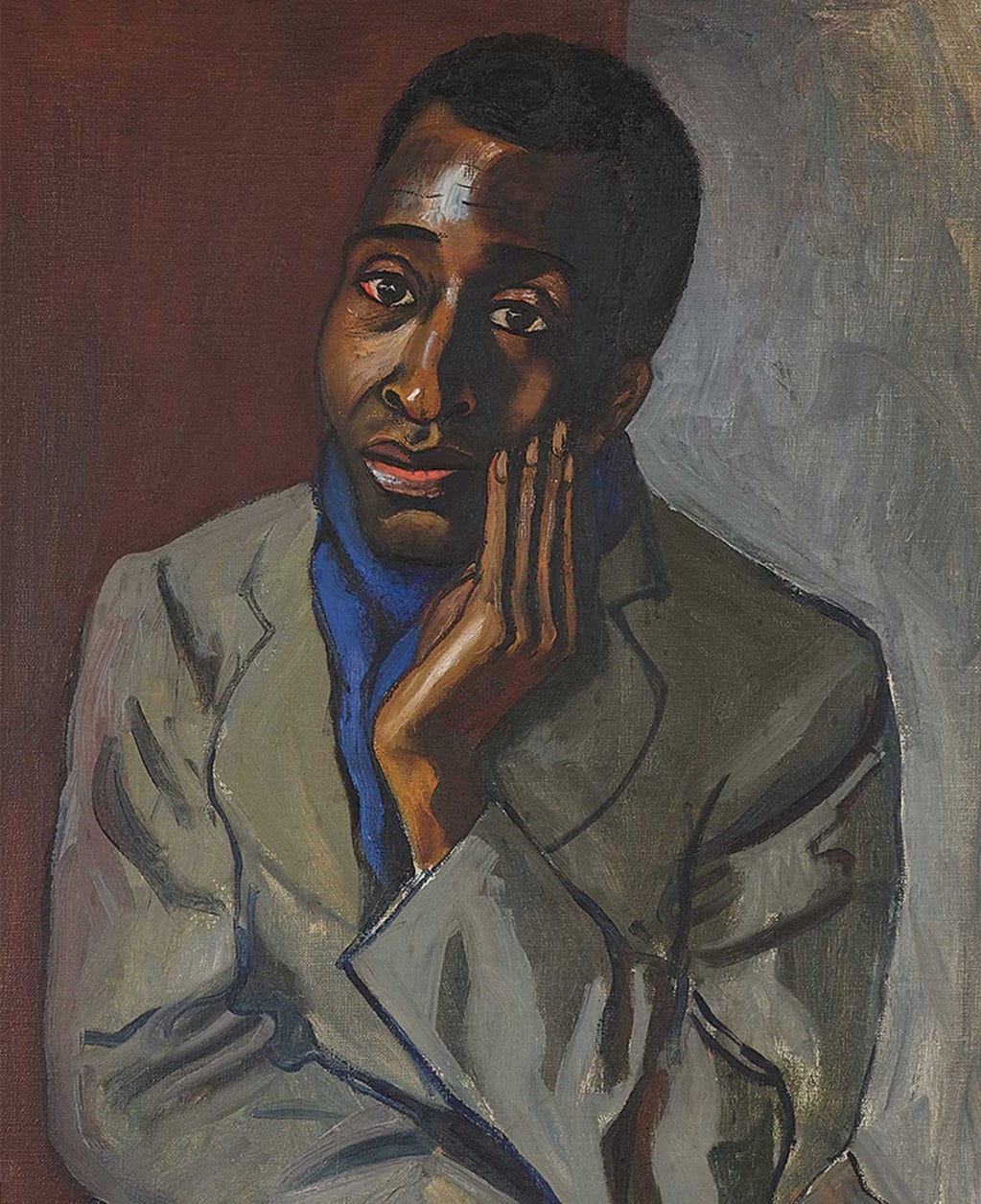

What this exhibition also draws our attention to, and what Als, an African-American critic and writer, wants to draw our attention to, is that Neel was one of the very few white artists painting people of colour. And she painted her black and Hispanic neighbours with as much engagement and sympathy as she did the black thinkers, writers, and artists who sat for her. Harold Cruse, who later published his magnum opus The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual, in 1967, looks in Neel’s 1950 portrait like a man burdened by concerns, momentarily adrift in serious thoughts, one hand raised to his cheek as if nursing a toothache in place of some existential pain. In the same year, Neel paints author, playwright and actress Alice Childress, who looks both coolly glamorous and pensive as she stares out of an apartment window. Meanwhile, two vitrines, containing photos, books and ephemera linked to some of the figures portrayed makes for absorbing documentation.

But easily the most striking portrait in the exhibition is the one of Vogue graphic designer Ron Kajiwara, 1971. The long vertical canvas accentuates Kajiwara’s already exaggerated thin, snake-hipped frame; and from his long hair to his high tawny boots, he simply embodies 70s cool. With one hand gesturing towards the viewer, the other on his hip, his full lips slightly parted, he seems caught in a moment which is part self-consciously posed and part spontaneous.

If you’re eager for a more comprehensive exhibition of Neel’s work, then there’s a major survey currently touring various venues in Europe, and which can currently be seen at the Fondation Vincent van Gogh Arles until September. But Victoria Miro’s sixth exhibition of the artist is more than a satisfying gap-filler.