Two titans of early twentieth century Viennese art at the Royal Academy

Egon Schiele’s artistic life was brilliant, short and full of scandal. Like Van Gogh, he packed a prolific and furiously intense career into just ten years. Gustav Klimt’s own brilliant career was not only longer but any potential impropriety that might have arisen over his exuberant love life was more the subject of discreet envy than gossip. And while Klimt was a decorated art star, Schiele had trouble getting a portrait commission.

In 1888, aged 25 (and two years before Schiele was born), Klimt had received the imperial Golden Cross of Merit for painting the ceiling of the grand staircase of Vienna’s prestigious new Burgtheater. Nine years later, Klimt was the founding member and first president of the Vienna Succession, whose motto was “To every age its art. To every art its freedom.” Viennese society loved and lauded him, and he loved it back.

But of course they had things in common. They died in the same year, as the Austro-Hungarian empire was falling. In January 1918, Klimt suffered a stroke, and a month later died of pneumonia, aged 55. Schiele drew Klimt in the morgue, with hollowed-out eye sockets and with his head tilted upright, floating in space. Later that year, Schiele, aged 28, succumbed to the flu pandemic raging through Europe. He died three days after his pregnant wife, whom he’d drawn on her deathbed.

Unlike Klimt, who would only paint one self-portrait in his life (as part of a decorative panel at the Burgtheater), Schiele was as absorbed by his own image – not least in cultivating it – as he was by the bodies and faces of the women, the men, the close family members (the disturbingly erotic drawings of his sister), the underage prostitutes and the wraith-like models he drew and painted with such electrifying immediacy. He drew them, and himself, as if their bruised inner lives were seeping to the surface, leaving sickly flesh livid and contused, with muscles in spasm and often enwrapped in a white ‘aura’, as if his wrought, twisted figures are radiating an unhealthy psychic energy.

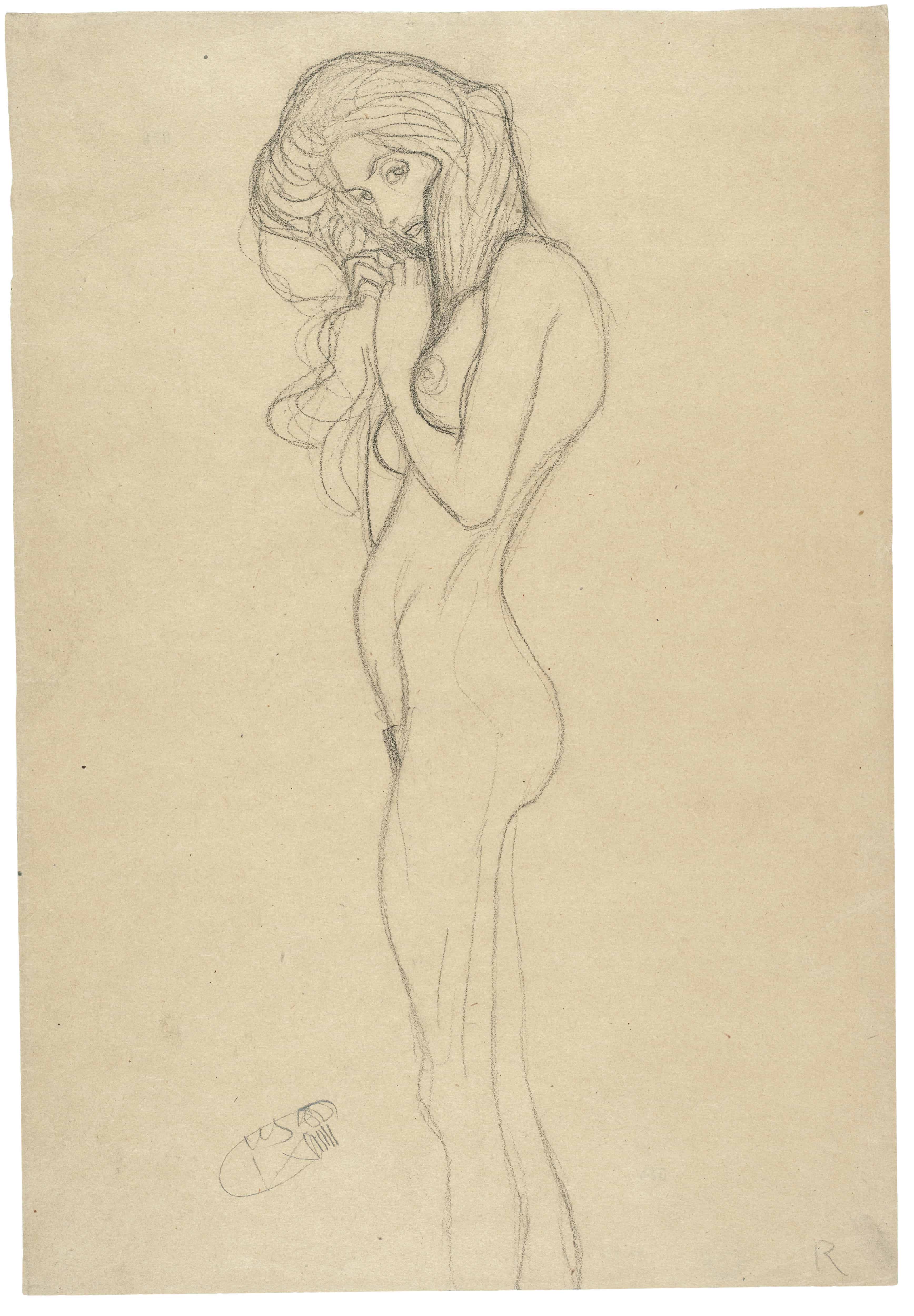

Schiele had been an ardent admirer of the older artist, from whom he’d drawn such inspiration as a student. But although both continued to draw on their fascination with sex and death – the Eros and Thanatos of the Symbolist imagination – which had found such fertile ground in the city that gave birth to psychoanalysis, their aesthetic paths radically diverged. There’s a cool, detached elegance to Klimt’s nudes, and in his more intimate drawings of women masturbating, made for the private gaze of gentleman clientele, there’s a soft, yielding eroticism that’s in marked contrast to Schiele’s brazen sexual confrontations by those whose sexuality suggests both a brittle vulnerability and a resigned insouciance.

The Royal Academy’s Klimt / Schiele Drawings cleverly – often brilliantly – illustrates these parallels and divergences, though the exhibition is necessarily limited in scope, since all the works are drawn from the Albertina Museum in Vienna. And it hardly does the older artist any favours.

It begins with the meticulous realism of early chalk drawings by Klimt, which are small studies of isolated figures for his mural Shakespeare’s Theatre for the Burgtheater. Those sketches, like the finished paintings, are studiedly academic and classical in style, though most of the later drawings in the exhibition are far looser, sketchier, the pencil marks often as delicate as a whisper.

Apart from the erotic drawings for private patrons, the only fully realised drawing that appears as an end in itself, that is, not a preparatory sketch for a frieze or a panel, is the 1897-98 Lady with a Cape and Hat. The lady in question has turned to look at us through heavy lids and with a melancholic gaze. Her face emerges from beneath a large, flouncy hat and cape, which are as inky black as the heavy shadows, while her languorous demeanour is further suggested by the soft tilt of her head. It’s an incredibly arresting image of a female type popularly depicted by art nouveau artists.

Elsewhere, Klimt’s drawings are not so impressive, a collection of rapidly executed pencil marks depicting a series of high-society women in patterned gowns. These might pass for fashion sketches, with the women mere mannequins. They pale besides Schiele’s electric dynamism in nearly every mark the younger artist makes, even when his own figures begin to resemble painted dolls, which, in fact, merely heightens a sense of tension.

You also begin to understand that for all his graphic mastery, Klimt is a decorative painter, his portraits and his erotic panels come alive with gilt and jewel-like colour and mosaic patterns, which means there’s more excitement in the jagged mark-marking and heavily scored lines that depict a row of houses by Schiele than there is in any of the preparatory sketches by Klimt. Schiele’s drawings and paintings on paper are finished and self-contained works of art after all, though it’s more than that. There’s an intensity and energy transmitted by Schiele’s very being.

So it’s clearly not just the subject matter of the abject and transgressive eroticism that grabs you with Schiele. A trio of single chrysanthemums are just as captivating, if not more so than the watercolour self-portrait where he depicts himself curled up in a rictus of despair in his prison cell.

In 1912 he had been – falsely it seems – charged with abducting a runaway 13-year-old, for which he spent three weeks in jail before going on trial. That charge was dropped and he was eventually convicted only of public immorality for openly displaying his drawings where young persons might see them, for which he spent a further three days in the clink.

This is a concise but rich survey of two of Vienna’s greatest artists. But Klimt’s elegant sketches just can’t hold a candle to work that crackles with such energy and acute feeling.