The Berlin and Beirut-based artist is one of six artists shortlisted for this year's Film London Jarman Award. He has also worked with Turner Prize 2017 nominees Forensic Architecture. He talks about the importance of sound, politics, and why he doesn't consider himself an activist.

Working predominantly with sound, video and graphics, Lawrence Abu Hamdan is one of six artists nominated for the 2017 Jarman Award.

He was born and grew up in Amman, Jordan, but is now largely based in Beirut and Berlin, having just started a one-year DAAD art residency in the German capital.

The 32-year-old artist had also spent just over a decade living in London, where he’s recently completed a PhD at Goldsmiths, in its Centre for Research Architecture.

As well as exhibiting audio-visual work which is often grounded in the politics of the Middle East, Abu Hamdan has worked with various refugee charities and advocacy organisations, including Amnesty International when he testified as an expert witness on behalf of defendants in asylum hearings in the UK.

The voice is such a potent carrier of emotion, so there’s a lot of human drama in your work, carried through both the voice and sound generally. Do you think that’s why you’re attracted to working with sound?

I think emotion goes through every register. I think we might just be better at hearing it in the voice, but it’s also very much embedded in what’s not said, in how people look or in their gaze. We haven’t yet explored fully the socio-political implications of sound and I think that’s why I’m attracted to it. When I was first interested in sound through music and had an experimental drive to play with sound and to push what music could be, there was never a sense that sound had a political dimension to it. Now I think quite differently. It’s very fruitful to think about sound, and the sounds of specific events, as a mode of socio-political analysis. Sound often amplifies forms of political representation that are perhaps not clear, or are perhaps occluded by the image or the way we’re normally trained to look at an event with our eyes.

Do you find it easier to work in Beirut, since much of what you produce is focused on Middle East politics?

For the time I was living in Lebanon, my work was focused on the politics around me, but when I was in London I was very much engaged with issues that were prevalent here. And the fact is it actually emerges from here [the UK] – the whole way of thinking through sound came from my studies here and meeting people here who do that kind of work for legal investigations. Among my first projects in London were ways of policing asylum seekers in the UK. So actually it’s a misunderstanding that the work is only embedded in the Middle East; I’m very much informed by that which surrounds me.

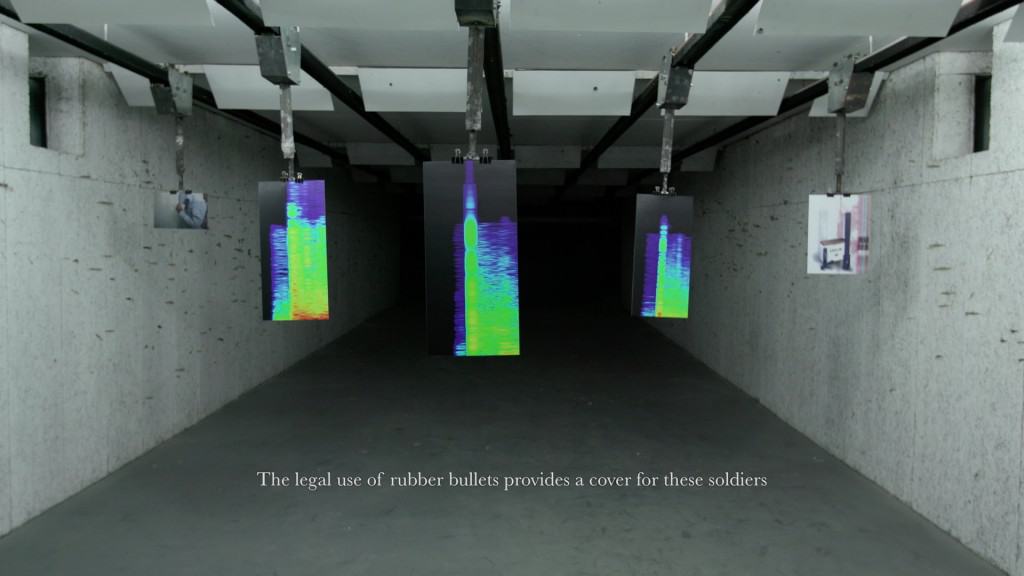

I was very taken with your installation at Maureen Paley earlier this year and with your two works, This whole time there were no land mines and Saydnaya (ray traces). For Saydnaya, what was it like to work with survivors, where prisoners are kept blindfolded 24-hours a day and where very few actually survive the torture.

I was there to work with those survivors for Amnesty International and with Forensic Architecture, which is an investigative agency based at Goldsmiths, and what we had to do was try and piece together a place that was for them really at the very threshold of perception. They [the prisoners] hadn’t seen anything, and most of what they’d experienced and what they could attest to was sound. That often meant they remembered sounds as images, since things got transformed in the memory. So it was really a very fragile form of testimony that demanded its own kind of language.

The testimonies oscillated between being incredibly lucid and where it was kind of hallucinatory. That was very challenging, but also very rewarding as an artist, because what was needed was the creation of a language in which to speak about that prison, and that’s what artists do: they create language for things that are unspeakable. And that formation of a language – playing tones and sounds, sound effects from films, mimicking sounds with our mouths – they all help to fill in the gaps for things which are very difficult to describe, both because of the extent of the violence inflicted on them and their traumatic nature, but also because of the inadequacy of speaking about sound.

How did you get involved in this work?

I got involved because of Forensic Architecture. They’re an agency who use the skill of designers, artists, computer programmers for the investigation of state level violence. And whenever they have an investigation that demands a sound analysis I usually work with them on that.

You’ve also testified as an expert witness in asylum hearings in the UK. What was that experience like?

They were doing accent tests here in the UK for those who came to into the country undocumented. So they would do tests to see if your accent was the same as where you said you came from. And you can imagine that this creates a whole range of disputes. And it’s a completely phony, unscientific way of understanding where someone comes from. I was working on behalf of the defendants for Amnesty international. Children International and No Borders are two of the organisations who’ve also used my work.

Do you consider yourself in any sense an activist?

No, because I don’t do the labour of activism. The labour of activism is organising, getting a clear message across for your cause, getting people motivated. None of that is in the work I do, though the work has been used as and for advocacy and different forms of activism. I’m trying to use art as a medium through which we can think about politics, and reimagine how we might think about specific political situations.