French-Moroccan artist Bouchra Khalili is known for her deeply researched film installations that explore discourses of resistance against a legacy of colonialism and imperialism

Bouchra Khalili is a French-Moroccan film and multi-media artist whose projects explore discourses of resistance against a legacy of colonialism and imperialism.

She is one of five international contemporary artists nominated for the eighth edition of the Artes Mundi Prize, awarded to artists whose work engages with contemporary social issues across the globe.

Khalili’s video installations include The Mapping Journey Project, which documents the movement of individuals across perilous political borders. Her more recent film, Twenty-Two Hours, forms part of the Artes Mundi 8 exhibition, at the National Museum Cardiff until 24 February.

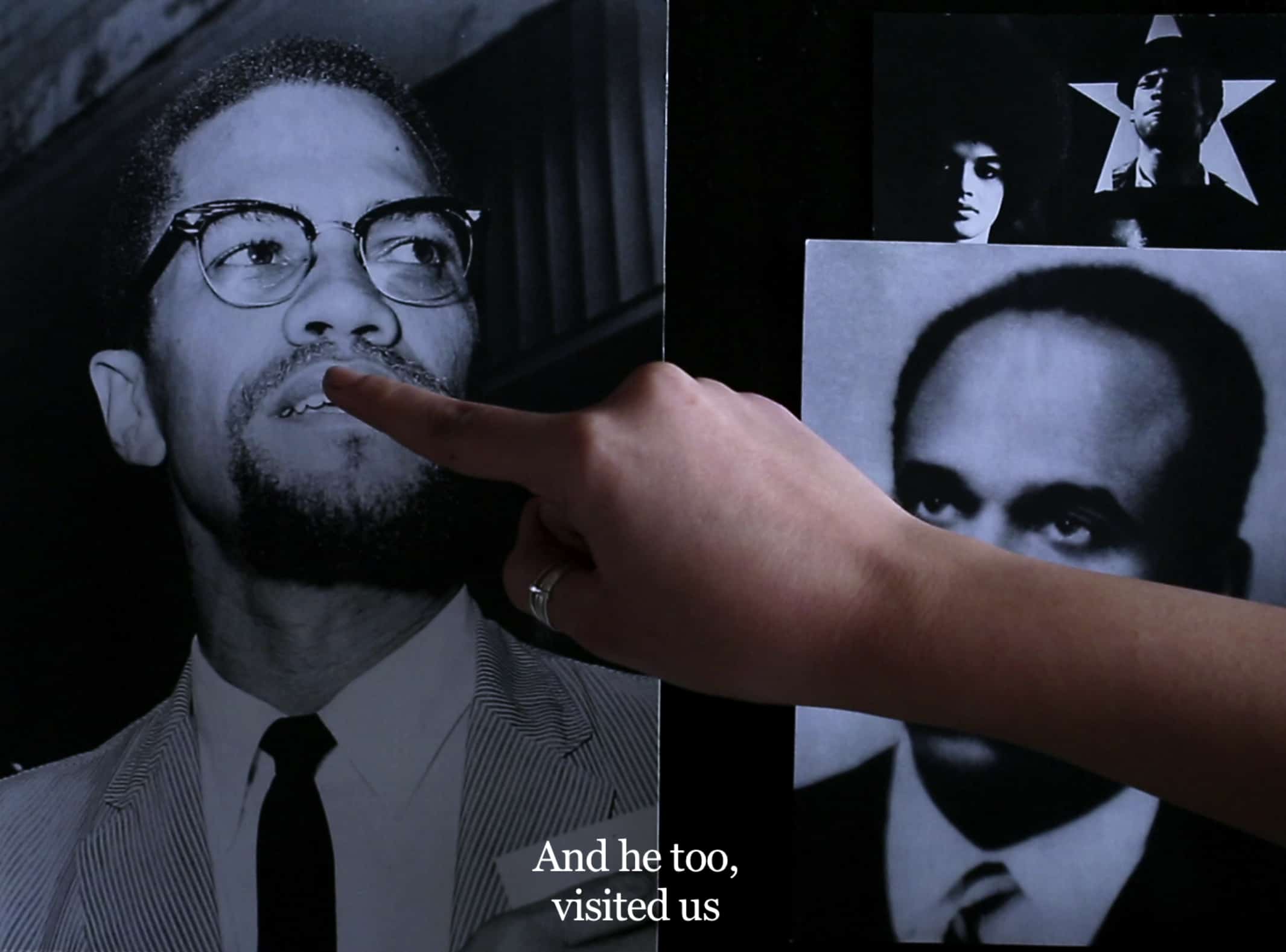

The film focuses on an episode in the Black Panther movement’s history, when French playwright Jean Genet campaigned for the release of Black Panther co-founder Bobby Seale during the New Haven Black Panther trials. The film also explores the movement’s continuing legacy as an inspiration for black activists today.

Khalili, 44, currently lives and works in Berlin and Oslo. The £40,000 Artes Mundi Prize is announced on 24 January 2019.

You trained as both a filmmaker and visual artist. What attracted you to making films that work within the gallery space rather than making films for a specifically film audience?

I was not trained in filmmaking but in film theory. And I was concomitantly trained as a visual artist. If I learnt something about filmmaking it is most probably through watching great films at the cinematheque and in art house cinemas that I used to attend as a teenager. But I never considered that the cinema room was the horizon of my practice. I actually rather prefer the gallery. First, because I work across various media – film, photography, printmaking – and that I consider that all of my works are eventually installations. Secondly, because the gallery operates potentially as an open arena.

When I was a kid in Morocco, I had the chance to attend what we call Al-Halqa, and that is sadly disappearing. Al-Halqa is the oldest identified form of performing art in Morocco, probably from the ninth century: a storyteller stands in a public area (a square, a plaza, a street corner, etc…), and narrates stories to an audience forming a circle around him. The word halqa refers to the circle, so here it is, the audience that defines the performance. The narrated tales happily mix stories borrowed from ancient poetry, popular tales and jokes, and parabolas on the current political and social situation. Somehow, I see the exhibition space like that circle: a space made for passersby who can stop for 15 minutes or for two hours. Within that situation, the viewer is neither alone nor captive as in a cinema room, but becomes a member of a collective.

What would you say are the significant differences between making a film for a gallery audience and making one for a film audience? And how does that difference impact your approach?

To me, the question ‘cinema vs. gallery’ is not an issue that enters into consideration within my practice. I’m much more interested in the exhibition space as a potential collective space, as a civic space and a space for the civic. When I first encountered the word ‘civic poet’ through my readings of Pier Paolo Pasolini‘s work, it sounded immediately familiar. I have known ‘civic poets’ in the form of the halqa, within the context of an old and traditional culture, that kept alive ancient although sophisticated and exquisite forms of oral narration and poetry, and that were not the privilege of an elite, but a shared and common knowledge. And what makes me happy above all is when I see viewers who start talking to each other, commenting on the works, engaging in conversations, or starting telling stories about themselves.

You grew up in Paris and now live in Berlin and Oslo. It’s often said there are more artists from elsewhere living in Berlin than in any other city, and Oslo is known for its high number of artist-run spaces. Were these factors important when choosing to live and work in these cities? And do you think that visible support for contemporary art and artists has helped your creative process?

I was actually born in Casablanca, spent my childhood there, and was later raised between Casablanca and Paris. Moving to Berlin was just a matter of chance: I was invited by DAAD [German Academic Exchange Service] for their [2012] artists’ residency programme, and I decided to stay after the end of the residency. I always liked Berlin, which I knew at a time when I never thought that I would become an artist. As for Oslo, I was offered a professorship at the National Art Academy and had no idea of the specifics of the Norwegian art scene. So teaching and spending time in Norway was more about having the opportunity to support junior artists with the development of their practice within the framework of the academy.

The point is that I lived in many different places, and produced works in many different cities in various areas: Istanbul, Ramallah, New York, Boston, Sao Paulo, Barcelona, Tangiers, Casablanca, Melilla, Athens. So I can’t say that support for contemporary art has influenced in any way the locations where I lived or worked. What I actually enjoy the most in Berlin is how quiet it can be.

Previous work, including your Mapping Journey Project, focused on migration and borders and featured personal testimonies of migrants. Your own story is one of continuing migration too. How did your own migratory background shape your perspective when exploring these issues as an artist?

I never considered that The Mapping Journey Project was about migration. I produced that installation between 2008 and 2011, at a time when the issues of migration were not making the headlines. What conducted me to produce many works on those who are defined as ‘migrants’ and who I rather see as ‘citizens deprived from their human and civic rights’ is the fact that I have inherited from a double history organically linked: the history of the struggle against colonization and the history of immigration. But it is also certainly connected to my own memory of Morocco in the ’90s.

As an example, I can still clearly remember the summer of 1991. Spain had just signed the Schengen Agreement. The country, whose southern coast is only a few miles from Morocco’s northern shore, was closing its doors to its African neighbours. Crossing the border became literally an obsession for the whole youth in Morocco, not because they were aiming to reach a so-called Eldorado, but because leaving the country was the only way to challenge social determinism and what was at the time still an oppressive regime. It’s not by chance that most of the videos forming that installation end with similar words: ‘I want to live a normal life’, which one can understand as ‘I want to live like those who have rights’.

Furthermore, there’s one single video of that installation rarely mentioned in the reviews of that work, although I consider it as the key node: Mapping Journey #3. That single video is about a young man living in Ramallah, in love with a young woman living in East Jerusalem. He cannot visit her, because the vast majority of Palestinians from the West Bank cannot go freely to East Jerusalem, although according to international law, East Jerusalem is a Palestinian territory. So, this young man has no other option than climbing hills, hiding from armed military patrols, and walking a whole day to go to East Jerusalem to see his fiancée, while by car it wouldn’t take him more than 20 minutes. For this young man risking his life to go to East Jerusalem, to see the woman he loves, is a gesture of resistance against the occupation. So, that young man from Ramallah is not a ‘migrant’ – he’s a stateless citizen living today under occupation.

Now, if one looks closely and with history in mind at all the maps, what one sees are borders implemented by colonial and imperial history. What the participants in the project do is to draw their own maps with permanent markers, replacing those colonial borders with their own trajectories, eventually suggesting a geography and therefore a history as well as a continuum of political resistance. That’s why I see all my works as a meditation on radical equality, examining the same question: how do we rethink the concept of civic belonging freed from the nationalistic history of citizen membership?

Your film for the Artes Mundi exhibition looks at the Black Panther movement, addressing both its failures and the way it still informs black American activism today. What was the direct inspiration for making it?

To answer your question, I need to give a sense of context. I started working on Twenty-Two Hours while I was developing Foreign Office (2015), a mixed-media project produced in Algiers. Foreign Office was investigating the internationalist era that followed the independence of North African countries. It focuses on the headquarters of movements of liberation based in Algiers between 1962 and 1972, including the International Section of the Black Panther Party. It is now forgotten, but the BPP had a great prestige and aura in North Africa, the same way that the struggle for independence of Algeria and the related writings of Frantz Fanon on colonialism inspired the party.

In Foreign Office, the photographs and prints capture the ghostly presence of the headquarters of movements of liberation in Algiers, still haunting the city. The digital film shows two young Algerians in their twenties investigating the forgotten history of Algiers, as it was the ‘Mecca of Revolutionaries’, to quote the famous words of Amilcar Cabral. Foreign Office and Twenty-Two Hours mirror each other: both show young people taking the burden of history. Both films include an investigation on the legacy of the Black Panther Party. Both films rely on a visual apparatus shaped as an editing room where storytellers turn themselves into film editors, rearticulating visual and sound material, to eventually become the historiographers of a history for which they now bear witness.

You locate it within a specific moment of the movement’s history, during Jean Genet’s involvement in the trial of Bobby Seale. It’s the moment the movement is literally falling apart, but also gaining international recognition.

I won’t say that Twenty-Two Hours is about the failure of the party, but rather about how its struggle for equality and social justice still haunts the present time. As for Genet, his presence operates as an epitome of unconditional and radical solidarity.