The only way to appreciate the 15th century master is by taking a tour of central Italy. Now with the help of a new app, it’s easier than ever to track down his must-see frescoes.

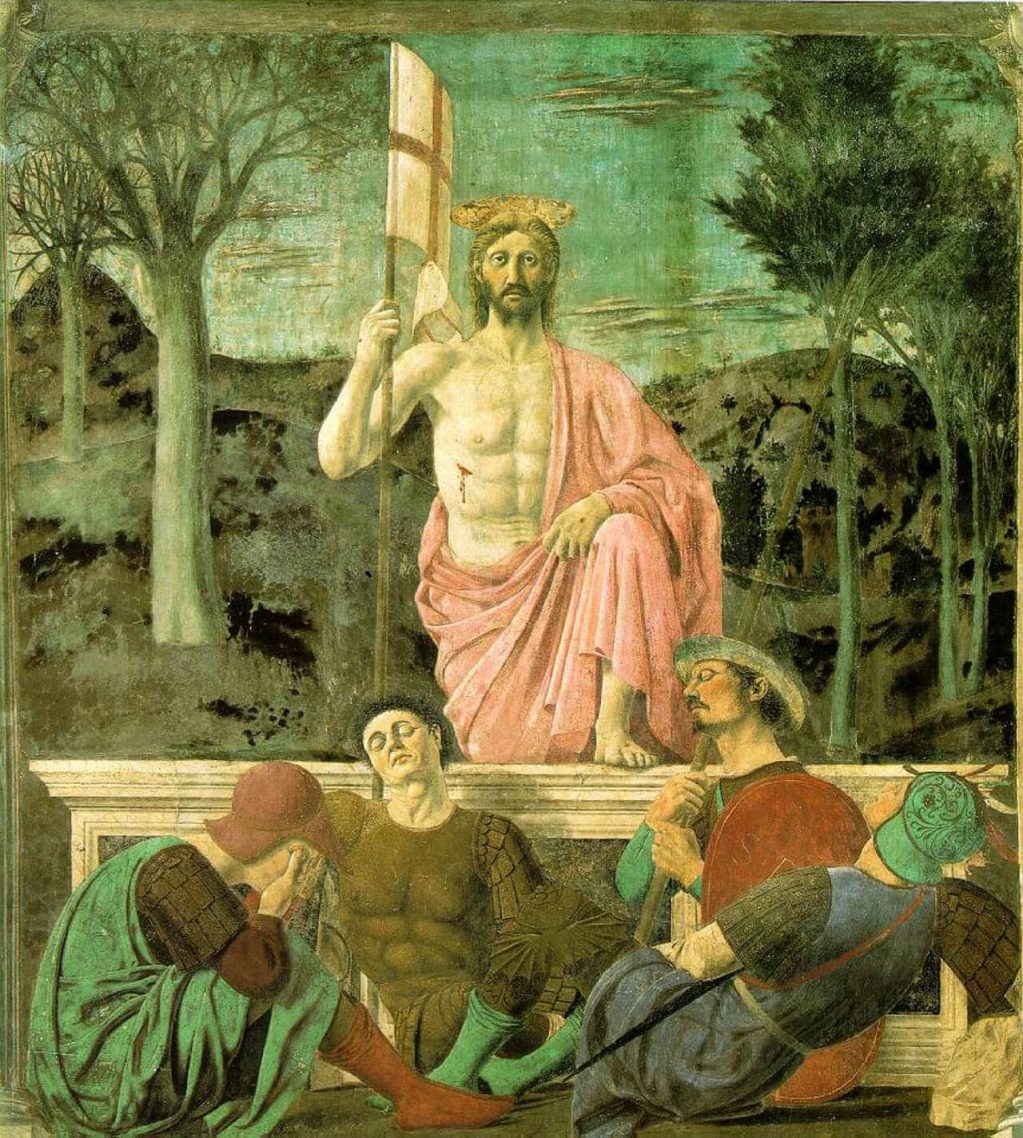

Piero della Francesca is today acknowledged as one of the foundational artists of the Renaissance; Aldous Huxley thought his Resurrection “the best painting in the world”. His compositions marry art and science with cool precision and a sophisticated grasp of perspective – he was, after all, a mathematician. But he was only rediscovered in the mid-19th century after centuries of relative obscurity. Following his death in 1492, his artistic achievements faded in the memory and he became known chiefly as a geometer (his numerous writings include an innovative treatise on solid geometry and perspective).

This is not wholly surprising. Many of the most impressive paintings in Piero’s oeuvre are not to be found conveniently in major museum collections (though the National Gallery does own three panel paintings, including a damaged, and possibly unfinished, Nativity — Piero was a notoriously slow painter who very rarely adhered to commission deadlines). Rather they are found exactly where they were painted, in the provincial churches and palaces they were commissioned for. To see them one must embark on the “Piero trail”, which takes in the artist’s birthplace of Sansepolcro — where you’ll find Huxley’s favourite — as well as Arezzo, Rimini, Monterchi and Urbino. When Huxley wrote his panegyric to The Resurrection in 1925, these regions were still quite difficult to get to. Very few art connoisseurs would have seen the images, even in reproduction.

Piero tourism has caught up somewhat. Today, you can access a new app for the trail, which enables you to locate the exact topographical spots believed — though not without contention — to have inspired the panoramas in some of Piero’s paintings. Observation points, known as Piero’s Balconies, high up on the rugged hillsides between Sansepolcro, Rimini and Urbino, have been meticulously mapped out by academic researchers Rosetta Borchia and Olivia Nesci. Here you can while away sun-dappled afternoons.

The Resurrection (probably executed around 1467–68) was painted for the Meeting Hall of Palazzo dei Conservatori di Sansepolcro, now the Civic Museum. In it we find the solidly built figure of Christ (described by Huxley as “athletic”) standing with perfect equilibrium and a perfectly elliptical halo above four dozing soldiers, one of whom, the equally broad-chested and muscular soldier in a brown tunic, is thought to be a self-portrait. Like his much older Netherlandish contemporary Jan van Eyck, Piero liked to put himself in the picture.

The painting is currently under restoration, in a project partly financed by the Italian businessman Aldo Osti. A former executive of a Sansepolcro-based food company, he stepped in with half of the £160,000 needed to save the painting, although the work is being done by the state. It’s scheduled to be unveiled later in the year, but visitors are invited to see it from a specially built viewing platform as it’s being restored. This will be the second time the painting has been “saved”: one of the favourite stories attached to the fresco is how, during the second world war, British army officer Anthony Clarke defied an order from his commanding officer to turn artillery guns on the town. With amazing serendipity, Clarke had read Huxley’s essay and could not bring himself to instigate the painting’s destruction. Luckily, the Germans fled shortly after, but the town still has a street bearing his name.

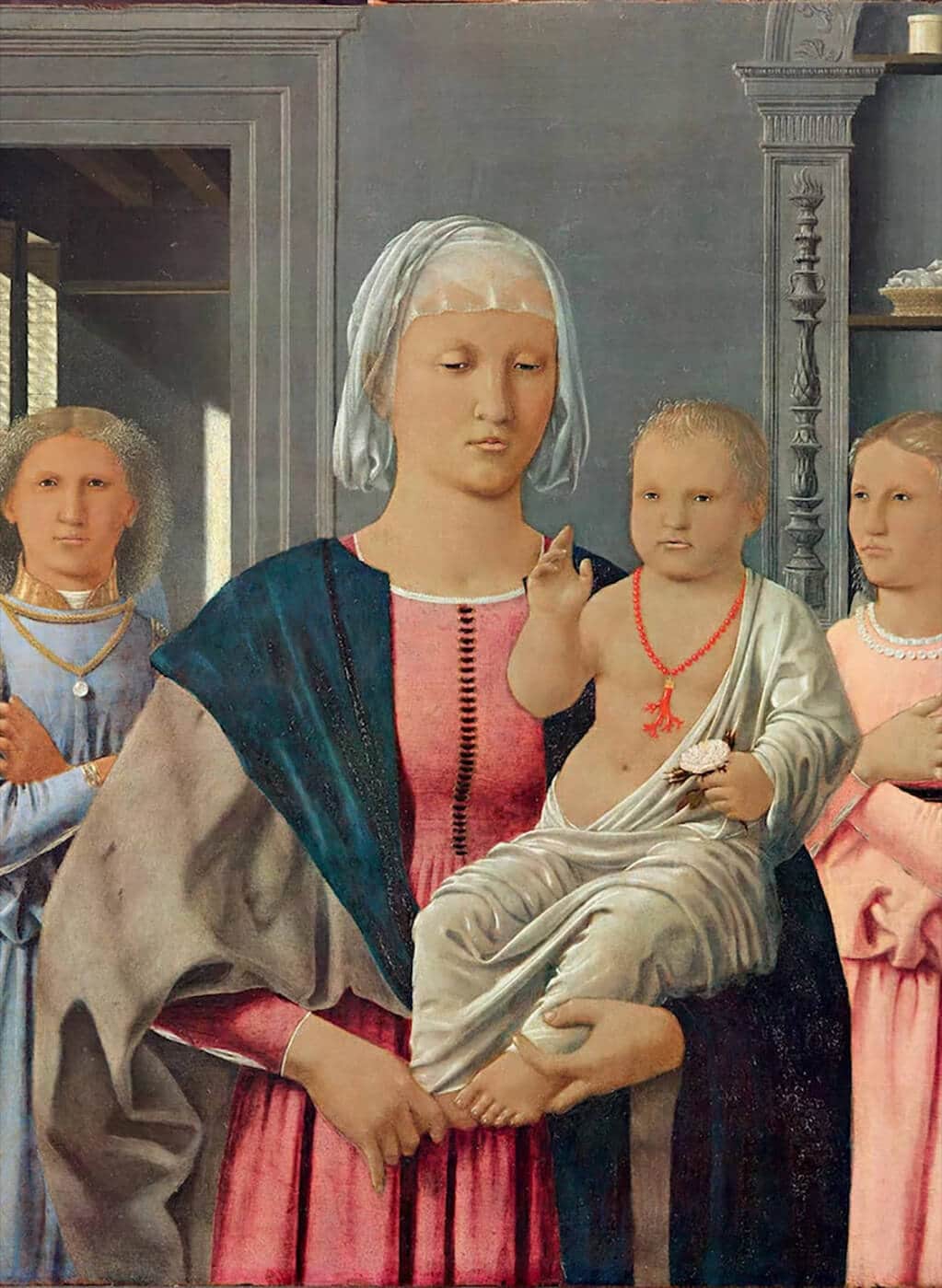

The Resurrection, which may well be the first picture to play with two vanishing points, symbolises renewal: barren trees on the left, trees covered in foliage and clouds subtly lit by the rising sun on the right. Piero’s paintings are innovative on many fronts, including in their use of different types of pigment, but what undoubtedly makes them so arresting is the beguiling strangeness of the eyes of his figures. Has there ever been a Christ that stares so fixedly and unsettlingly at the viewer? You’ll find this again when you visit the ducal palace in Urbino (where you may also wish to visit Raphael’s childhood home, now a small museum). Here you’ll see the perspectivally complex The Flagellation of Christ, 1455–60, and the sublimely serene Madonna di Senigallia, 1474. The Virgin’s robustly full-bodied femininity (no fragile wilting beauty she) is certainly striking, but it’s the angel on her right who unsettles. If he was painted as a figure to penetrate the very soul of the believer, it does the trick.

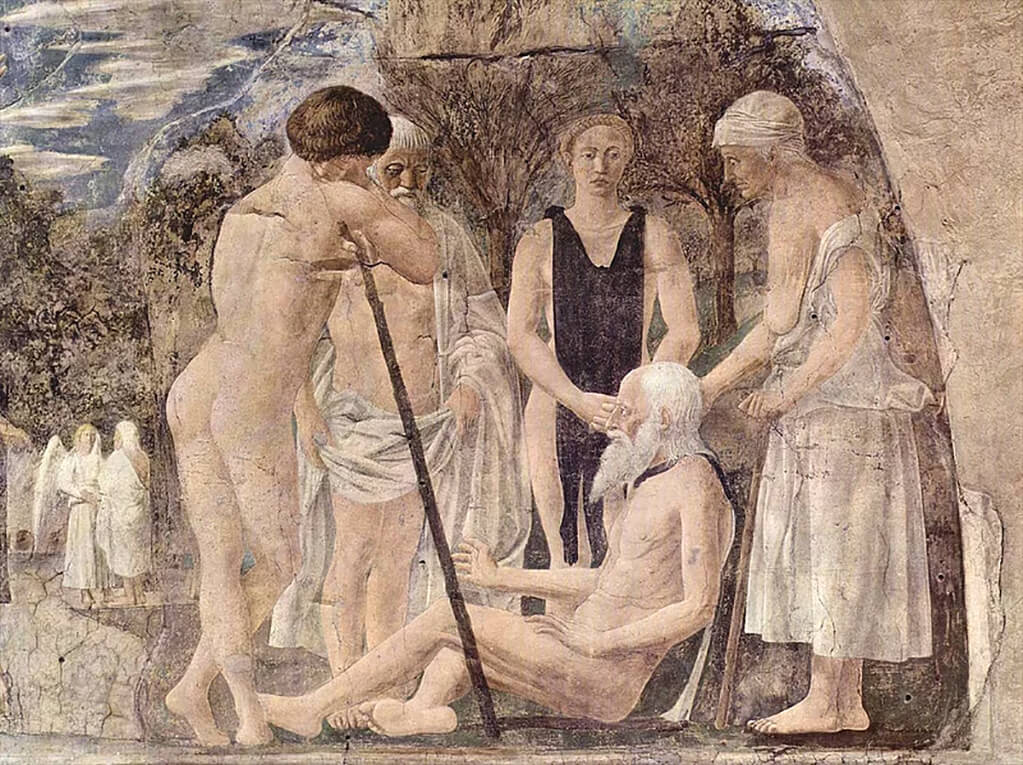

Monterchi’s fresco Madonna del Parto is a must-see, a rare depiction of the pregnant Virgin, who looks little more than a teenager, again with that perfectly elliptical halo. If pushed for time, dare I say, you could skip Rimini, where you’ll find the 1451 fresco Saint Sigismund and Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta exactly where it was painted at the Tempio Malatestiano (much of the pigment is gone), but Arezzo must surely be the trail’s highlight. Completed in 1466 and recently restored, the church of San Francesco houses The Legend of the True Cross cycle, which begins with the Death of Adam and ends with The Exaltation of the Cross. Superlatives have been expended aplenty. It’s enough to say that it’s one of the wonders of the early Renaissance.