Helen Cammock explores the idea of multiple histories in her powerful film 'Shouting in Whispers' at Cubitt Gallery. Here she talks about the importance of words in her work, and discovering the writing of James Baldwin.

Helen Cammock is one of the shortlisted artists for the 2017-19 Max Mara Art Prize for Women, which offers the winner, announced next year, a six-month residency and exhibition at Whitechapel Gallery.

Cammock’s heavily researched, multi-media work, which embraces film, photography and print-making, addresses themes of social justice and ideas related to historical cycles.

Having worked as a social worker for more than 10 years, in 2008 Cammock graduated with a BA in photography from the University of Brighton, completing an MA at the Royal College of Art in 2011.

She is currently showing her hour-long film Shouting in Whispers, at Cubitt Gallery, London, alongside related work. Previous films include There’s a Hole in the Sky Part I and There’s a Hole in the Sky Part II, the latter imagining a conversation between the artist and James Baldwin.

Writing is at the core of Cammock’s work. She borrows the words of others to use alongside her own, including those of Baldwin, Maya Angelou, Walter Benjamin, Frantz Fanon and Jamaica Kincaid to retell previously silenced and omitted histories.

Your film Shouting in Whispers is a beautifully edited collage that includes the protests in South Africa under Apartheid, the Palestinian struggle, Greenham Common, the Brixton Riots, and so forth. This sense of history not being in a sense historical, of the struggle never being over, is very powerful in your work.

I believe quite strongly in the idea of multiple histories. Obviously there are dominant histories, but then we have omissions, silences. For me, these are also histories. And if the omissions aren’t explored or probed, then we have this lack, and I think that’s why, in some ways, we have these cycles – events that keep happening at different times and different places. The film is like a visual essay exploring this idea.

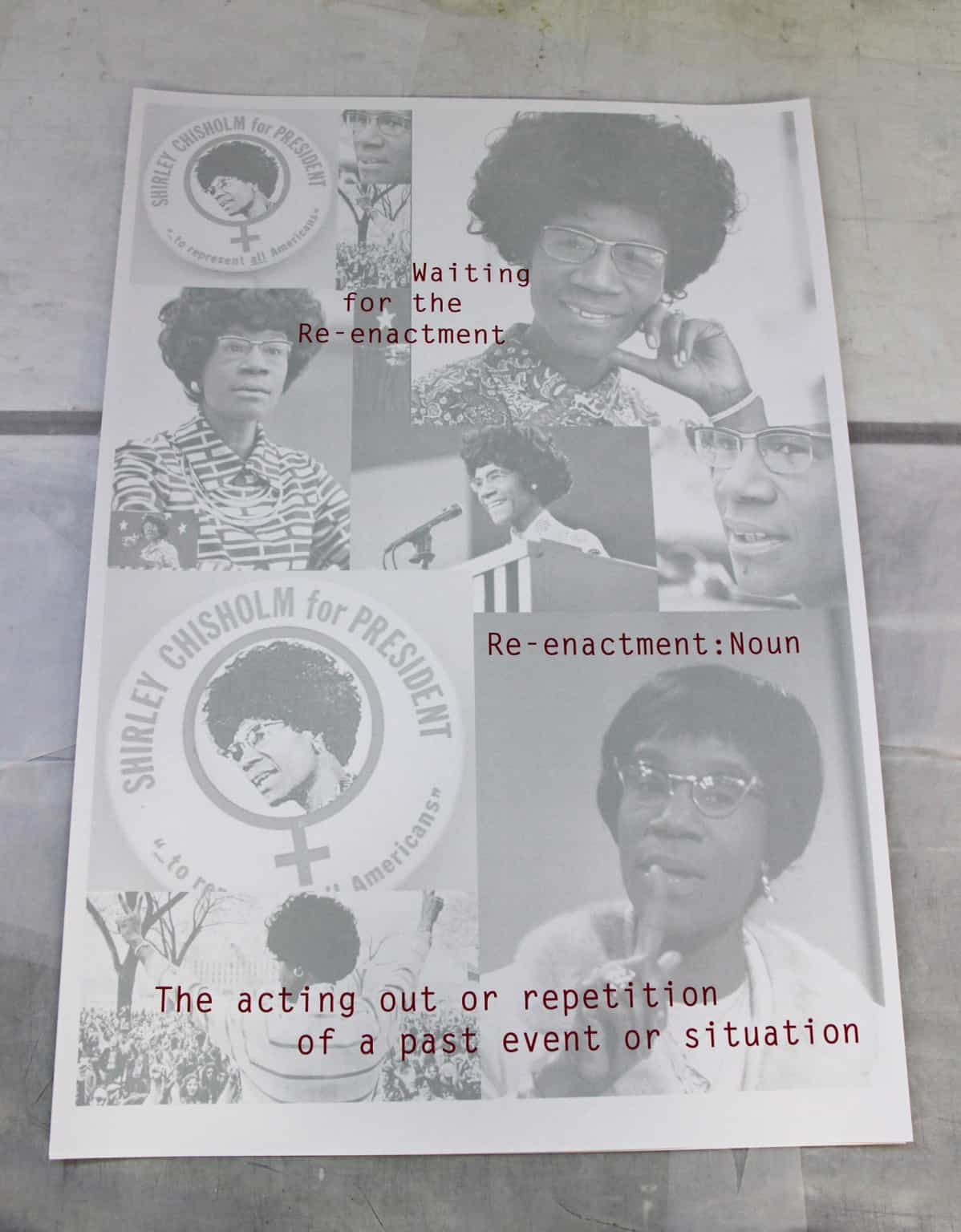

In some ways the film is a tribute to Shirley Chisholm (the first and only black woman to stand for the Democratic presidential nomination, in 1972). She seems to speak so strongly to us today, in the era of Trump.

I know. As soon as I saw that footage I was like, yes, that’s exactly my reaction. I was completely struck by it. She’s speaking to us now.

In your work you use songs, prose, poetry. Words, your own and that of others, are just as important as the visual image.

Yes, absolutely. I’ve been trying to think about this recently because I think language and text is probably the driver for everything I do. So whether it’s me writing or whether it’s me reading or speaking or singing, it forms the core.

Let’s talk about the influence of James Baldwin in your work. For instance, in an earlier film, Hole in the Sky Part II; Listening to James Baldwin, you and he engage in an imaginary conversation. When did you discover his work?

I probably found all the black female writers before I found James Baldwin. I was drawn to writers like Alice Walker, Maya Angelou, Audre Lorde, who were all looking at structural racism, but also storytelling. It wasn’t until my 30s that I discovered him for myself, after a conversation I had with someone, and they said, ‘What? You’ve never read any James Baldwin?’ It was the fiction first, before the essays. Then I got into watching interviews and some of the lectures he gave that you can watch on YouTube. He’s always there, he’s always in my head and because I became more interested in ideas around intersectionality, for me he represents that in a key way: the way he talks about queerness, the way he talks about blackness, the way he sees his role as an artist but also an activist. It speaks to me, and other people are now reading him and seeing the relevance of what he’s saying in the current context we’re living in.

It was round about this time, in your 30s, that you began a photography MA at the Royal College of Art. Before that you’d spent more than 10 years as a social worker. What was the impetus for such a radical change in your life?

It was a number of things. The first thing was social work practice and the cuts that were happening. I started to feel that the practice was dangerous and I got to a point where I’d had enough. It wasn’t a feeling that I’ve had enough of working with the people or families I was working with. Initially, it was about how I could bring something creative into the work I was doing – so it was never, ‘I’m never going to work with people again.’ It was more, ‘OK, I need to do it in a different way because I’ve had enough of working in the way that I’m expected to work, which is really not offering support or change for anyone.’

And the second part of this was that in my late teens and 20s I had sung. I’d been a singer-songwriter. So I’d always had this outlet where I could write and speak and sing some of the things that I wanted to say, and I’d stopped doing that when I was full-on working as a social worker. I was craving a creative outlet again. So I did an evening class in photography and found myself trying to formulate ideas and tell stories and learn a new visual language. I became completely hooked.

You said that photography is a very important part of your work. However, your exhibition at Cubitt uses images downloaded from the internet. Have you moved away from your own photographic work?

No, not at all. This exhibition was an opportunity to think about researching in a different way. I often think of myself researching using books, using libraries, using archives, and that’s quite an analogue way of working. This time I wanted to think about digital archives. I also think that when I work with a video camera [Shouting in Whispers also includes footage filmed by Cammock herself], I work with the camera almost as though it’s a still camera. I frame shots in a very photographic way. I think of this as the energised frame because there was something I wasn’t able to articulate fully with the still image. But now that I work with video and with print-making, I feel much happier working again with the photographic image. The thing that’s really important to me is this inbetween space – that space between the text and the image. So even though I say everything comes from writing, I could never lose the visual because it does something completely different. It either changes the meaning of what’s being said in the text or adds another layer to it.