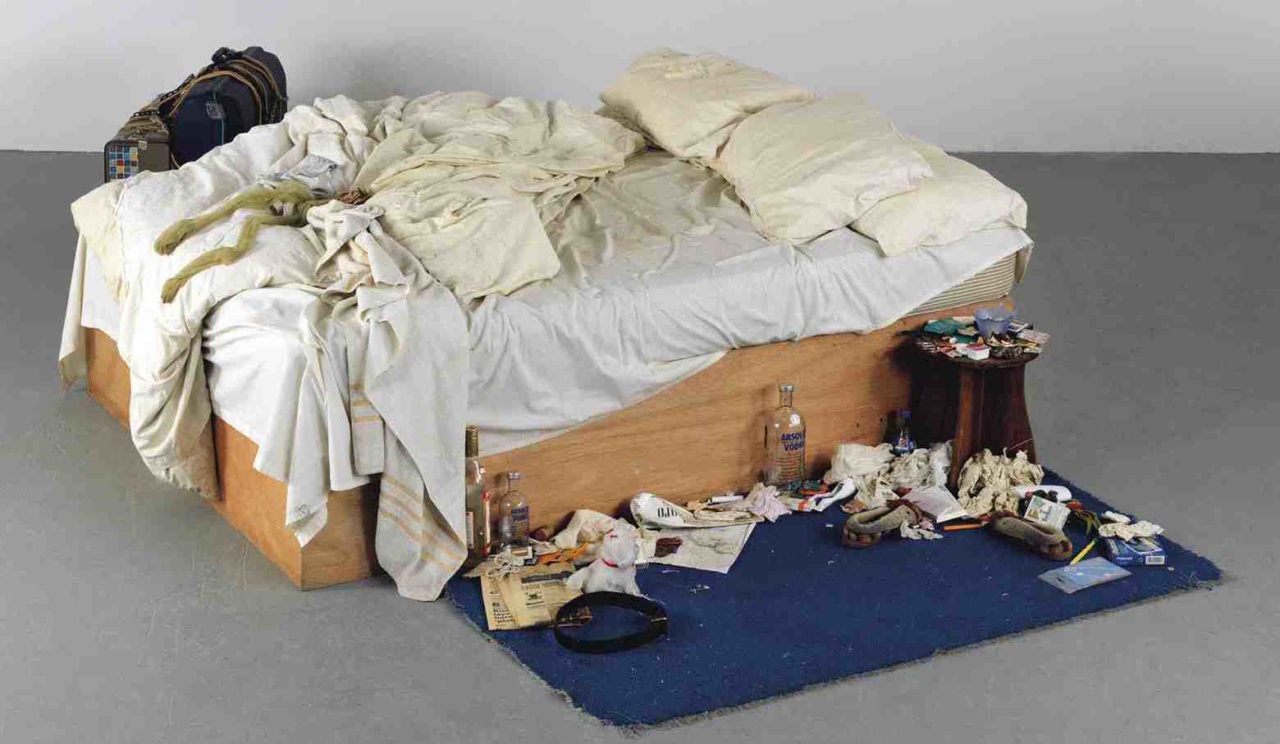

Emin’s bed, a Duchampian readymade, remains a potent expression of the artist's disorderly emotional life as a young woman

My Bed, one of the works that failed to win Tracey Emin the Turner Prize (she lost to Steve McQueen in 1999), made £2.2m at Christie’s this week, going to an anonymous buyer. Charles Saatchi, who put it up for auction, had bought it for £150,000 in 2000.

It has apparently lost none of its controversy since it first went on display at Tate Britain 15 years ago. And by ‘controversy’ I simply mean that many people – and that includes art critics – don’t think much of it at all. And note, I only use the term ‘controversy’ – and in scare quotes – because many sections of the media are rather wedded to it when it comes to anything do with Tracey Emin. I suspect that its use is really little more than lazy shorthand for the antagonism people, journalists, feel towards contemporary art in general. And that can get very boring.

Anyway, here I’m begging to differ. I love Emin’s bed. I think it’s good art, even though I don’t actually think it’s her best work. Her videos are her best work, because they are powerful and moving and because she’s a great story-teller in an avowedly traditional sense (I add that not as a plea to reassure, but because it’s true). For the doubters, just watch Why I Never Became a Dancer and you’ll see that her work has real narrative power.

She’s also, unsurprisingly, a very good writer, as anyone who’s read Strangeland, her 2005 memoir, will know. This has made some critics suggest that it’s writing (spelling aside) rather than visual art that’s her forte. And although I don’t think that’s true, it is true that her work has a story-telling function. Therein lies its seductive potency – but only if you’re prepared to be open to it. Visual art, unlike prose, operates on the condition of its obliqueness, its slipperiness, its open-endedness. Prose embraces all that too, of course, but not as a kind of unwritten condition of its power.

And Emin’s bed, that smelly, messy expression of Emin’s precarious and disorderly emotional life as a younger woman, operates on that level too. Like Rauschenberg (with Bed, 1955), Emin took the notion of the coldly dispassionate Duchampian ready-made (a real bed) and married it to the emotional heat of a confessional narrative. But Emin’s bed, as opposed to Rauschenberg’s, has a squalidly humdrum, English kitchen-sink feel to it. Her bed, after all, is just a literal thing, a literal bed with nothing added and nothing taken away, with all its surrounding accoutrements (bloody knickers, used condoms, cigarette stubs), transported into a gallery to look as if that’s how it always looked.

So it’s a bed with two histories – both Emin’s history and art history, in bed together, intertwined. It’s a conversation on all those levels, happening in that bed, and with all that unruly feminine emotional baggage too. And that’s why I’m rather taken with it.