Two exhibitions offer an overview of the modernist artist, yet Mondrian still eludes us

It’s 70 years since Mondrian died in New York, leaving unfinished his last painting, Victory Boogie-Woogie, an ebullient title quite at odds with the buttoned-up asceticism we normally associate with this artist. The Courtauld Gallery showed a small survey two years ago, which paired his flat grid compositions with the paintings and white reliefs of Ben Nicholson, focusing only on his two years in London (1938 to 1940). Though it proved surprisingly illuminating, in its precise, compare-and-contrast way, any exhibition promising a little more depth must be welcome.

Now we have two, concurrent and complementary (if geographically distant) surveys. Yet even if you put them both together they’d fail to provide anything like a complete picture of this most rigorous and austere of modernist artists.

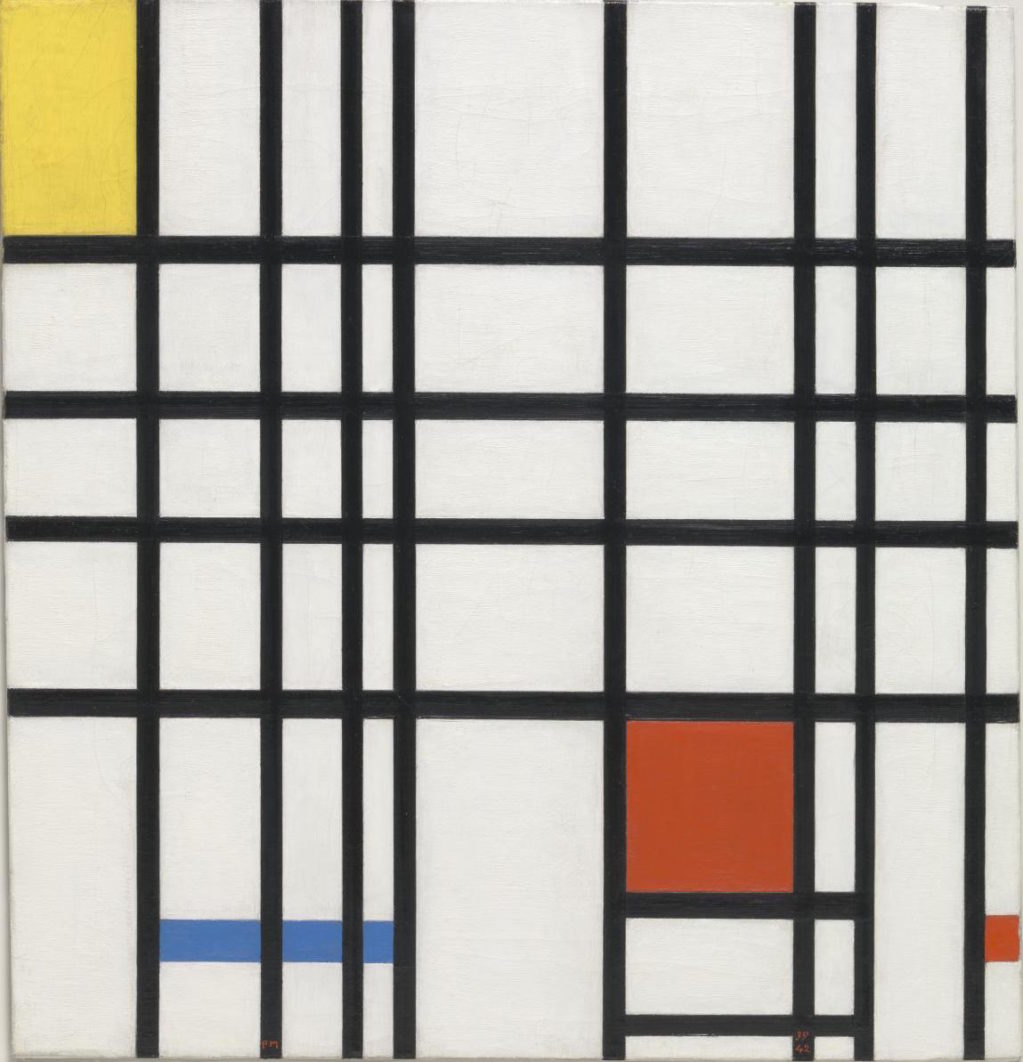

The smaller exhibition, at Turner Contemporary in Margate, features some wonderfully luminous painting. It looks at Mondrian’s early figurative canvases and the beginnings of his grid motif, and yet it never adequately explores that transition. The second, at Tate Liverpool, recreates his studios in Amsterdam, Paris and New York, and gives us, fully formed, the Mondrian that’s instantly recognisable to all: the black intersecting horizontal and vertical lines containing blue, yellow and red rectangles, against a white (initially grey) surface, in tautly balanced compositions.

The Tate show features no figurative works, but it does show how the paintings and the studio embodied the same “Neo-plastic” aesthetic principles. Following the De Stijl philosophy, the Dutch modernist movement which forged a synthesis between painting, design and architecture, his studios are, with their neat primary coloured wall panels and work surfaces and clean white walls, like 3D representations of his paintings. They look, at least to our eyes now, more nursery room than atelier. If Francis Bacon’s studio, containing the accumulated detritus of the artist’s long life, presents one extreme of the artist’s habitat, then Mondrian’s must present the other.

But if only we had one or two examples of the paintings he painted in the last four years of his life, to go with that last studio in New York. Their jazz-inflected, syncopated rhythms show what a difference America made, how re-energising this final journey. But one can only borrow what is readily loaned.

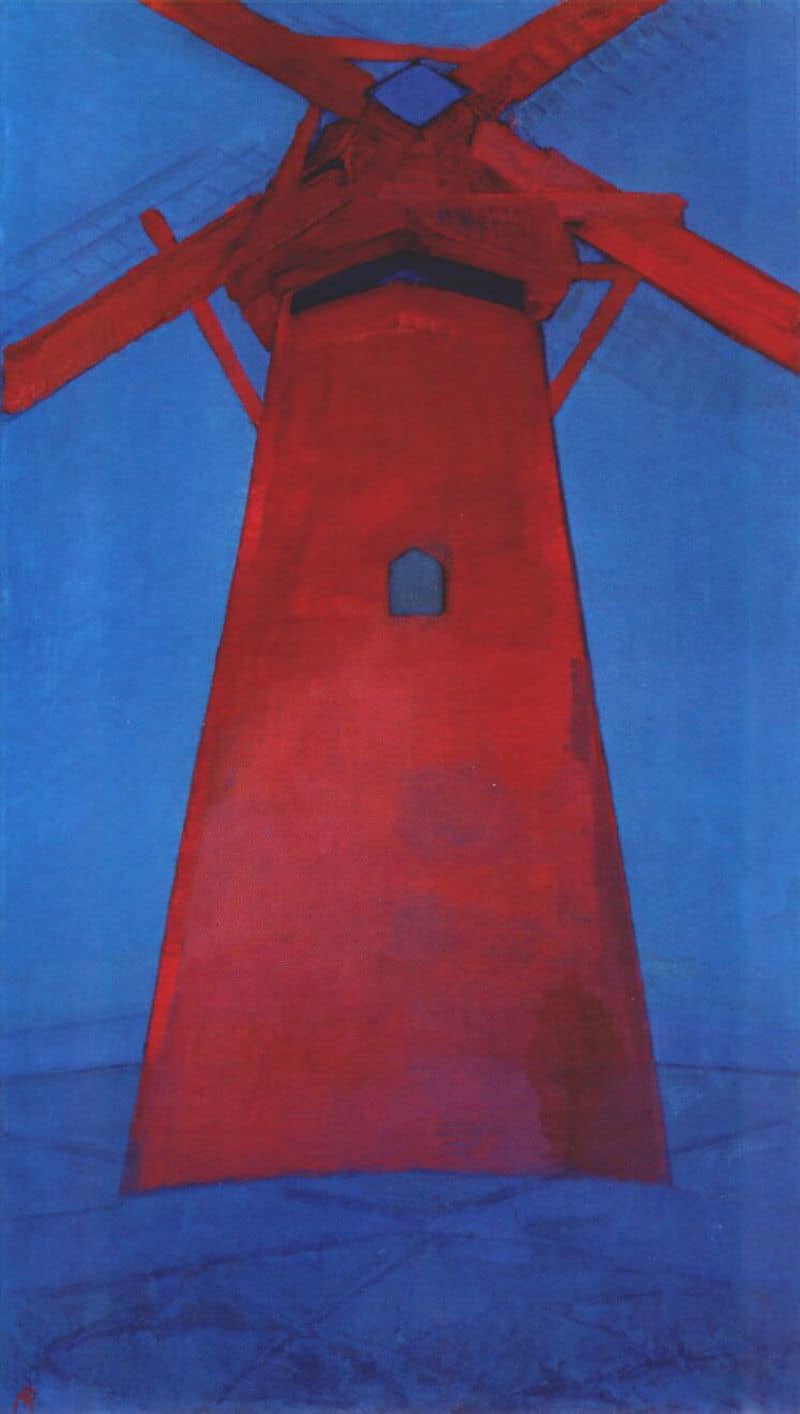

Comprising paintings which are mostly on loan from the Gemeentemuseum in the Hague, Turner Contemporary’s display is by far the most intriguing, not least because it features the paintings with which we are least familiar. It shows how the Dutch artist absorbed, in quick succession, one avant-garde style after another: 19th-century Realism, symbolism, Impressionism, pointillism. Each, with varying success, finds its moment. In one canvas, our eyes note the sinuous Art Nouveau lines formed by tree trunks in a dense, moonlit wood. In another, far more prosaic in execution, we find the square-set features of a Dutch peasant farmer made up with thick pointillist marks in pink and yellowish hues.

But all these stylistic flirtations are underpinned by a resolutely Dutch, or at least Northern European, sensibility. The earliest paintings here are in the manner of The Hague School, a dour Dutch variant of the French Barbizon School. Colours are dark and earthy – browns predominate – while forms are squat and solid.

As he becomes exposed to the French avant-garde, Mondrian’s palette lightens. But acid-tinged hues are favoured, with slightly discordant, cool notes over warm, harmonious ones. The exhibition is titled Mondrian and Colour, yet I feel it makes too much of the influence of Goethe’s colour theories. In 1909 he joined the Dutch branch of the Theosophical Society, that most modernist of creeds, and colours and forms become imbued with spiritual significance.

Turner Contemporary’s exhibition is by far the more seductive of the two, but we make a blind leap into abstraction far too suddenly. Crucial parts of the jigsaw are missing in this complex picture. There are no paintings from his single tree series which would illustrate the transition from figuration to the abstraction of interlocking lines beautifully. But limitations aside, one must acknowledge the compelling nature of this display. I’d urge you to pay a visit.