The paintings are wonderful, but the curator does a huge disservice to this forgotten artist

This exhibition makes me very sad. And not just because the subject of this long overdue survey died at the age of 28, and so left behind a body of work that stretches to only two very small galleries in the current exhibition, but because it does Pauline Boty, Pop artist and a contemporary of Peter Blake, a disservice.

Curated by Sue Tate and first shown at Wolverhampton Art Gallery (and so Pallant House insist they were not in a position to change anything), there’s everything wrong with this exhibition except the works that take us from the relative juvenilia of Boty’s short career to her last major work in 1966, completed shortly before her death from cancer.

One might begin with the title. Yes, there can be no denying that Boty was a woman, but so is Bridget Riley (both had been students at the Royal College of Art, with Riley preceding her by just a few years), but Riley is alive, and one can only imagine where she would tell curators to get off if they attempted to shoehorn and define her completely on the basis of her sex. If you can imagine such a thing ever happening to a male artist, what would the title “Painter and Man” (ridiculous, I know) infer? It would infer not gender but biography – a promise of a glimpse beyond the paintings and the persona to the person. Since “he” is default, identifying “the man” would not be an attempt to pigeon-hole him in terms of his “gendered perspective”. Yet apparently, this ceaseless “gendering” (I apologise for the verb) is absolutely OK for a female artist, as long as it’s coming from an apparently “feminist perspective”.

Boty, unfortunately, has no say. And so this means that on and on and on do we read of her “gendered” perspective – an adjective either used on almost every other label or else inferred throughout the exhibition, so that the paintings simply aren’t allowed to be or to breath as works of art in their own right but only as a reductive schema to the fact of Boty’s sex. I will go further and say that I find this not only grating but dehumanising – is there no other “perspective” from which Boty might have viewed the world? One is therefore forced to ask: is it really progress to talk about women being historically sidelined as artists and then to go on to straitjacket them by other means, according to another agenda, by prescriptively interpreting their work in such a reductive manner? But such is the tunnel vision of many curators, especially if they have special academic interests to promote.

But this isn’t the only problem. The curator’s position on British Pop art is just plain wrong. Tate writes that Boty “eschewing the detached position adopted by the male pop artists, expressed the lived experience of the fan.” Really? From her “gendered perspective” you say? If you knew nothing about Pop art you might even believe this confidently asserted nonsense.

In fact, one begins to wonder if Tate herself is at all familiar with the movement that Boty was at the centre of. Did Boty’s friend and fellow RCA graduate Peter Blake “adopt a detached position”? You wouldn’t think so if you saw any of his paintings. Isn’t Blake, for instance, actively expressing his “lived experience as a fan” of American popular culture in Self Portrait with Badges, 1961? – his love of Elvis, in particular (he’s holding a fanzine with Elvis on the cover, which might be a clue). And what about his series of paintings of the masked wrestler Nagasaki? Do they not also express the “lived experience of the fan”?

I could go on. So, OK, I will. What of David Hockney’s early Pop paintings? (He too, though briefly, appears in Ken Russell’s 1962 film for BBC’s Monitor strand, Pop Goes The Easel, which featured Boty and Blake, along with Derek Boshier and Peter Phillips). Is Hockney’s Dollboy, expressing the young Hockney’s desire for the then hip and sexy Cliff Richard (oh, those really were the days), also “detached”?

So when one looks at Boty’s Portrait of Derek Marlowe with Unknown Ladies, 1962-63, how is one meant to understand it as an example of a uniquely different perspective? But again, according to the label, through the act of painting Marlowe, the sexy British novelist, in a vaguely realist style, while above a parade of women’s stylised faces provide a decorative border, Boty “critiques the imbalance of power between the sexes”.

In fact, Boty had painted a similarly composed painting featuring Christine Keeler, which she called Scandal. That painting is now lost but can be seen in tiny reproduction in a magazine spread. It shows Keeler in her famous pose astride a chair, while a frieze of stylised male faces is shown at the top of the painting. But, of course, comparing these two paintings, similar in composition but with genders switched, would not fit so neatly into the curatorial thesis. So it’s not mentioned. And, incidentally, the frieze device was also employed by Peter Phillips in his paintings of sexy women. It’s a common Pop motif, so not just used by Boty, and almost certainly not to “critique the imbalance of power.”

This leads one to believe that the curator is either ignorant, or else she wishes to stick rigidly to an agenda despite everything presented to the contrary. So it’s essentially a lie. But hang on – what of Boty’s use of lace in her early collages, or the recurring motif of the red rose? Surely she uses lace because, from her “gendered perspective”, it’s closely associated with femininity. Yes, I suppose there’s nothing too outrageous to suggest that association, but then we learn that she makes copious use of lace in one collage, which is a study for a stage design for Jean Genet’s play The Balcony, because this is what the author had specified for the set. Could it not be that Genet influenced Boty’s use of lace in her other collages too? Just a thought. But, no, Boty is simply not allowed to respond to the world in any way other than the curator’s way.

None of this is to say that Boty wasn’t aware of her sexuality, or her status as a woman in a male-dominated arena, nor that she didn’t deploy this awareness in her paintings. In life she was incredibly beautiful and acquired the nickname “the Wimbledon Bardot” shortly after arriving, aged 16, at Wimbledon Art School on a scholarship. Later, she posed for magazine spreads wearing lingerie, and acted in television dramas and on stage. She was a gorgeous hip young scenester – looking more like a knowing Julie Christie, in fact, than a sex kitten Bridget Bardot (the film Darling, starring Christie, is said to have been inspired by her) – and, yes, she caused heads to turn and men, no doubt, to fall at her feet.

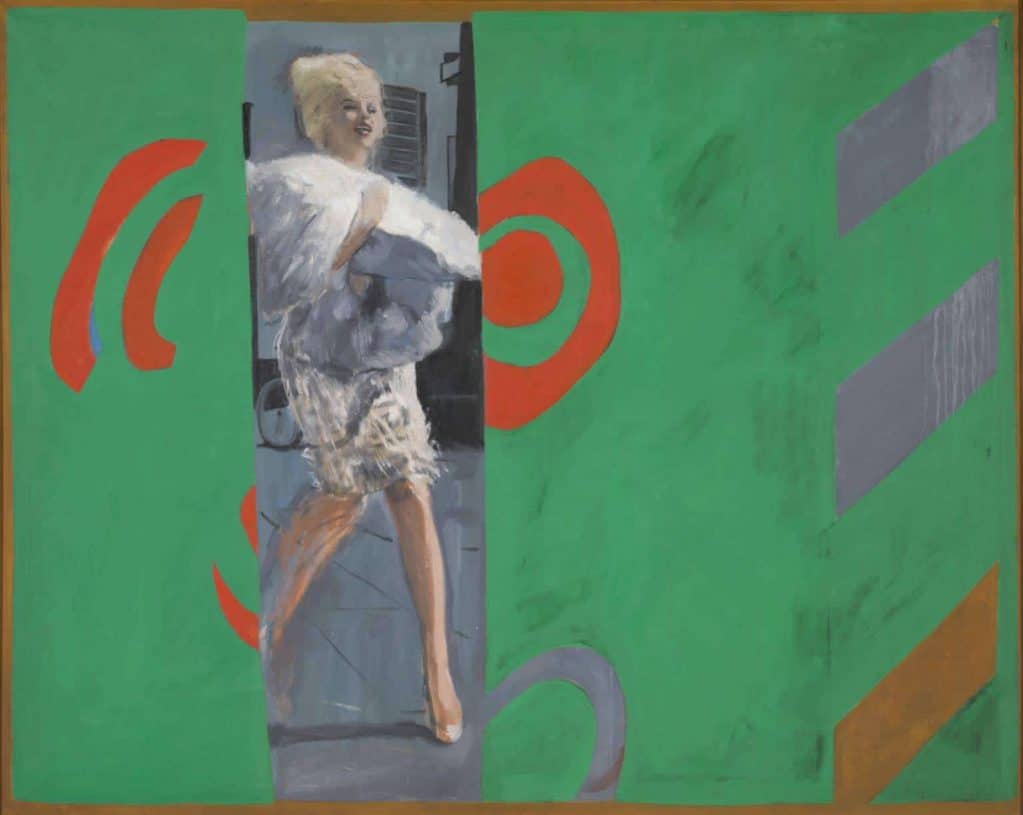

All that is true, yet none of it excuses the curatorial blunderbuss. That Boty appeared to identify with Marilyn Monroe, the enduring Pop icon, might also be true. In her 1963 painting, the cheekily ironic The Only Blonde in the World Monroe is featured swathed in furs and striding centre stage between two funky abstract panels. It’s a wonderful, exuberant painting, as is the striking Colour Her Gone, 1962, made poignant because it was painted shortly after Monroe’s death. But Boty also identified as an artist and a painter, and adopted the visual language and iconography of her milieu – we are not short of Pop Marilyns – and so to offer overly prescriptive and misleading interpretations is inexcusable.

Nonetheless, I want everyone to see this exhibition. Boty was a significant talent, as this first survey of her work attests. But do allow the work, for once, to speak for itself. This is an exhibition which accords little respect for its subject’s autonomy. And the day I see an exhibition called Peter Blake: Pop Artist and Man is one I look forward to.